Today you’ll be given a chance to workshop the argument for your apology section. You should bring a draft of your argument along with the map or whatever preparatory materials you used to construct it.

All Courses Apology Workshop Day

Today you’ll be given a chance to workshop the argument for your apology section. You should bring a draft of your argument along with the map or whatever preparatory materials you used to construct it.

For this class, Scheffler’s concept of being homeless in time is one of the most important parts of this chapter. The notion is similar to temporal mobility in the sense that we cannot control our movement. However, temporal mobility refers to individuals occupying space. It is true that we cannot control our movement at all times, but we do have some influence on our surroundings at certain points in life. For instance, one can control whether they attend class one day or not. In that sense, one expresses ownership over the possibility of occupying a classroom. Now, Scheffler is consider the ownership of time. According to him, it is not possible to express ownership over time, even in an insignificant amount. It is a dimension humans simply cannot express ownership over. Time is a constantly moving force and individuals have no control over its direction or magnitude. In this way, humans have no ability to occupy time itself.

Temporal mobility refers to the notion that humans cannot control our movement through time. While we may be able to influence our movement or actions in particular moments, we have very little influence on the broad scope of our entire life. Regardless of our wishes, time is always moving forward and we must adapt to it. While Scheffler notes that this is often taken for granted, it is a frustrating fact of life. As individuals (supposedly with free will), we expect to have full dominion over our lives; yet, we cannot master time and its influence over us. According to Scheffler, these circumstances emphasize the importance of tradition. A particular practice repeated at regular intervals enables an individual to have ownership over at least some aspects of one’s life.

Normativity refers to an evaluative statement as to whether something is desirable. It is important to distinguish normativity from positivism, which postulates one should only make claims based on empirical evidence. A positive statement makes a claim as to how things are, whereas a normative statement makes a claim to how things should be. A normative statement seeks to attach a belief or expectation to already established facts. To understand this distinction, refer to the following example:

Positive Statement: “Jake’s dog is a German Shepherd.”

Normative Statement: “German Shepherds are the best breed of dogs.”

Scheffler provides a definition of tradition that provides insight into his understanding of the term and its significance in human culture. Read it below as context for the rest of the digital essay. This is what Scheffler means by “tradition”:

Two points of clarification are in order. First, in one broad and standard sense of the term, a tradition is a set of beliefs, customs, teachings, values, practices, and procedures that is transmitted from generation to generation. However, a tradition need not incorporate items of all the kinds just mentioned. In this essay, I am interested in those traditions that are seen by people as providing them with reasons for action, and so I will limit myself to traditions that include norms of practice and behavior.

Second, there is a looser sense of the term in which a tradition need not extend over multiple generations. A family or a group of friends may establish a “tradition,” for example, of celebrating special occasions by going to a certain restaurant, without any thought that subsequent generations will do the same thing. Even a single individual may be described as having established certain traditions, in this extended sense of the term. [B]ut my primary interest is in the more standard cases in which traditions are understood to involve multiple people and to extend over generations.

The transition from personal salvation to universal redemption marks the transition of humanity from pursuing evil to seeking the good. Once an individual realizes that satisfying one’s pleasures and self-interest is not worthy, as it provides no meaning to life, one will instead actively look for goodness as a higher source of meaning. This leads one to pursuing God and developing a close relationship with God, actualized through acts of justice and mercy in pursuit of a better world.

One should note also that this redemption is universal. Heschel draws a distinction between his argument and personal salvation, arguing that simply pursuing the latter is another form of self-interest. Rather, the way to truly prevent suffering is committing oneself to salvation for the entire world, which he terms as universal redemption. It is through this method that humanity can become closer to God and end evil in the world.

Here, Heschel refers to the prophets of the Hebrew Bible who frequently criticized the Israelites for various offenses against God, such as worshipping false gods. An interesting notion that Heschel introduces here and develops in the subsequent paragraphs is a distinction between history and redemption. For him, history refers to human activities, ripe with the injustices and suffering associated with the pursuit of human self-interest. This is separate from the redemption, which refers to a state of affairs beyond history that involves concepts of salvation, the kingship of God, and other faith-based ideas. Heschel uses this distinction to separate the evils of our world from the goodness of God, counteracting the illusion of evil he mentioned earlier in the excerpt.

For Heschel, “alien thoughts” are ideas that enter one’s mind that dissuade one from pursuing righteous actions. He believes that even if an individual pursues good acts and remains faithful to God, foreign concepts will enter one’s thoughts with the mission to drive them away from God and goodness. This exacerbates the tension between God and humanity because it is rooted in human self-interest.

One of Heschel’s concerns is that God’s will and human nature are inherently opposed to one another. He believes that humans are naturally selfish and pursue ends that benefit themselves, even at the expense of others, which inevitably leads to situations where one will sacrifice piety or adherence to God’s will for some other goal. The desire to pursue self-interest introduces deceitful thoughts that drive one away from God and a life of holiness. Heschel also believes that self-interest contributes to suffering in the world. To prevent evil, humans must work towards rejecting their pursuit of self-interest through activities like faith and following God’s will.

Heschel is also concerned with how good and evil can often be confused for one another. What appears as holy and good may actually be evil in disguise around the illusion of self-interest. An example is worshipping a false idol. One may believe that their act is holy and upholds God’s will, but according to Heschel, the act only reinforces the evil and sinful nature of the world.

Here, Cohen is describing humanity grappling with the concept of absolute evil once it has entered reality. He argues that prior to the tremendum, the notion of absolute evil was simply a concept that existed in the mind that was thought to never exist in the real world. This enabled individuals to justify “relative evils” that were comparably smaller to the absolute evil that existed only in human consciousness. However, the Holocaust demonstrated that absolute evil, suffering and horror exercised without rationality or moral consideration, is certainly possible in this world. For Cohen, this means that there are no more excuses for the relative evil because the absolute evil is as real as it.

Cohen uses the term “vector” similar to mathematicians and physicians, in that it refers to something that has both magnitude and direction. When he says reason has a “moral vector,” he is suggesting that rationality is accompanied by moral considerations that drive the process of reasoning. Cohen believes that moral principles and rationality are intertwined, in that morality is rational and rationality is moral. As a result, any rational conclusion must also be morally acceptable. For this reason, Cohen notes that an evil like the Holocaust cannot be rational because it is not moral in any sense. Likewise, it cannot be moral because it is not rational.

What do you think of Cohen’s intertwining of reason and morality? Do you think that rationality has a moral vector? Should reason and morality be inherently connected or separate? Can someone reason something that is not moral?

Tremendum typically means “awefulness, terror, dread” and other similar feelings. Here, it is Cohen’s term for the Holocaust. He uses this term because he believes there is no evil equivalent to the Holocaust, so using the terms typically used to describe mass suffering is not an adequate description. He adopts the word tremendum because he believes it best captures the horrible realities of the Holocaust compared to other available terms, although it still ultimately falls short because humanity simply cannot comprehend the true extent of the events that took place during the Holocaust.

Mipnei Hataeinu is Hebrew for “because of our own sins” and refers to the concept that humanity’s suffering is brought about by its sins. In other words, destruction and pain are punishments for sinful behavior. The interpretation would suggest that humanity deserves this chastising, as indicated by Isaiah 59:12: “For our transgressions against You are many, and our sins have testified against us, for our transgressions are with us, and our iniquities – we know them.” Mipnei Hataeinu reveals that punishment is justified because it is a response to humanity’s sins, similar to how a parent might discipline a child.

However, recall that such an explanation for the Holocaust does not suffice. There is no rational explanation for anything committed by the Jews that would warrant such a devastating slaughter and genocide. For this reason, Berkovits rejects this view and instead relies on the free will argument to explain why God would permit the Holocaust to occur.

Hester Panim is a Hebrew phrase that means “hiding face” and is used commonly in Jewish biblical interpretation. It refers to the concept of God literally hiding Himself from the suffering of humanity. As the Torah (the Hebrew Bible) demonstrates, there are many times that God rescues the Israelites from devastation, whether it is being brought against the Israelites or they committed the evil themselves. Hester Panim is usually interpreted as those times that God does not save the Israelites. It is interpreted as a punishment for not following the covenant or breaking God’s laws. Some scholars take a less vindictive approach, believing that God hiding Himself is an act of love and compassion because He cannot bear to watch His people suffer, similar to how a father does not want to watch his son get hurt.

Berkovits uses an entirely different interpretation of Hester Panim, drawing from the Jewish concept of nahama d’kissufa (Hebrew for “bread of shame”). Nahama d’kissufa refers to the notion that greater satisfaction derives from being deserving of a reward than simply receiving it as a gift. For example, giving yourself a dessert as a reward for doing well on an exam is more meaningful than simply eating the dessert. Berkovits argues that God granted humanity free will to make our achievements more significant and worthwhile. As a result, God must distance himself from humanity to enable humans to exercise that free will to the greatest extent. This inevitably allows evil to occur in the world, as any interference by God to prevent evil would undermine humanity’s free will.

Here, Marx argues that in practicing religion, man becomes alien from his own life. How might other philosophers, such as Aquinas or Nietzsche, agree or disagree with this claim?

Key Terms: Objectification and Alienation: Marx defines a sort of two-pronged process of objectification and alienation. He defines objectification as the process of labor becoming a commodity in itself– and alienation refers to that commodity becoming something that is separate from the laborer.

Key Point: Stoicism is an ancient philosophy known for its emphasis on wisdom, virtue, and harmony with divine reason. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/stoicism/

The Grand Inquisitor was the lead official of the Inquisition, appointed by the Church. During the Inquisition, a time infamous for the torture and execution of heretics, the Inquisitor was a powerful authority figure in society. Note that Dostoevsky does not portray the Inquisitor as evil, but rather as a character whose aims are understandable.

A heretic is a person who has been baptized as a Christian but doubts or denies established religious principles. In the sixteenth century, the time when Christ is reborn on Earth in this story, heretics were executed or even burned at the stake during the Inquisition.

Key Term: remote effects refer to more distant and difficult-to-anticipate consequences that someone’s actions may have, ex. someone’s decision to take public transportation to save on gas costs may unwittingly cost a car salesman their job.

Ernest Partridge was an environmental philosopher who wrote extensively on duty to future generations. You can find more of his work on his website, The Online Gadfly, a title with a clever reference to Socrates. This website, according to his obituary, is also a virtual monument to continue on his legacy and work into the future.

Taylor is a Canadian philosopher and professor emeritus at McGill University known especially for his work related to political and historical philosophy. Taylor has critiqued Liberalism, naturalism, and secularism throughout his long career. He will be 90 in November of 2021.

Here Kavka is accounting for population growth or decline.

Otherwise known as the Lockean Proviso, this idea is that a person has a right to the property that they put work into as long as in claiming this property there is enough of that quality resource left for others. In other words, no one is worse off with that resource claimed.

An English Enlightenment philosopher, John Locke is known for his political philosophy and work on epistemology and metaphysics. Kavka is drawing from his writing in section 4 of the second treatise in Locke’s Two Treatises of Government.

There’s a distinction here…. not nec strongest possible reason, all things being equal, no one is required to have millions of kids.

Remember Kavka’s previous argument about contingency: if it is certain that there will be no future people, then they have no moral weight.

The “contingency” of people is the last concept that Kavka grounds his discussion on. The idea is that we cannot be certain as to whether future people will exist at all; in some respects, we can only assume that they will, but there’s always a chance that they won’t.

The term “temporal location” refers to a thing’s existence in a particular time. This concept is the basis of Kavka’s first point in the following section.

Kavka calls this “the more modest conditional conclusion” because it leaves open the possibility for further discussion. If someone does not accept the initial premise that “we are obligated to make sacrifices for needy strangers” then they do not have to accept the conclusion that they must sacrifice for future generations.

A telling title to his essay, “futurity” refers to all future time and events. Kavka will wrestle with the moral challenges that arise when we consider the obligations futurity imposes on us in the present.

When Ivan says “I hasten to return my ticket,” he is referring to the possibility that he might be rewarded in the afterlife after suffering in this world. Ivan cannot rationalize any argument that might justify unnecessary suffering and refuses to participate in such a system. This is where Ivan rejects the harmony, participating in what his brother deems rebellion.

When Dostoyevsky uses the term harmony, he refers to the belief that one’s suffering in this world is worthwhile because it will be rewarded in the afterlife. Ivan is adamantly against this idea, explaining that future benefit does not justify current suffering. If someone is sent to Heaven after having suffered immensely, it does not erase that the suffering happened in the first place. For Ivan, no future benefit can justify the current injustice of suffering.

Here, Ivan is referencing Jesus giving the Great Commandment. The verses (Matthew 22:35-40) of the passage are below.

And one of them, a lawyer, asked him a question, to test him. “Teacher, which is the great commandment in the law?” And he said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it, You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the law and the prophets.

Even after receiving a wage that is less than the value they have contributed to production, the proletariat must give much of their earnings to other members of the bourgeoisie in order to survive. For Marx, capitalism places the proletariat in constant subjugation to the bourgeoisie.

Marx argues that capitalism provides unjust wages to the proletariat. Think about the process of capitalism: a business owner provides resources, a worker produces a product, the worker receives a wage for that labor, and the business owner sells the product. For the business owner to have a profit, the selling price must be higher than the wage earned by the worker. Marx contends that this process devalues the worker’s wage, and therefore their humanity. This suggests that capitalism, as a system, dehumanizes and oppresses the proletariat. For capitalism to survive, and profit to exist, the proletariat must be devalued.

Just as the proletariat are reliant on labor to survive, they become an object to the system. Similar to the products they produce, the proletariat are bought and sold by the bourgeoisie to benefit the capitalist system.

Here, Marx argues that in capitalism, workers are only valuable to society if they are productive. When he says “labour increases capital”, he means that the proletariat’s work must contribute to the wealth of the bourgeoisie for the proletariat to survive. If a worker is unproductive, they will be deprived of a wage and will lack the resources to live. This is a key part of Marx’s criticism, that survival is dependent on productivity.

This is one of the most famous phrases from The Communist Manifesto. Here, Marx argues that the bourgeoisie, driven by a constant need to expand their markets (and therefore wealth) are forced to fundamentally change society. The simple, laboring feudal lifestyle is replaced with industrial machines creating elaborate products with little effort. Thus, capitalist relations of production tend to spread geographically, as well as into more and more areas of human life.

A key part of Marx’s theory is that common laborers have been reduced to wage earners and that this is bad for human well-being. For Marx, work is an essential part of human identity. It is a way of human flourishing, because your work is an extension of who you are. However, Marx contends that industrialization has led to the commodification of work — a worker is the kind of thing that a price is put on, that bourgeosie trade. Instead of doing your job simply for the sake of it, the proletariat are forced to work only to survive. And even then, the work is more and more disconnected from human life – it is reduced down to simple tasks alongside machines that have further dehumanized the work experience. When Marx says these individuals have become “paid wage labourers”, he is criticizing capitalism’s deteriorating effect on the value of work for individuals.

Aristotle also used knife imagery to talk about the purpose of human beings. For him, a good knife is one that fulfills its purpose (a sharp knife!), and a good human is someone who lives as a rational animal to the best of their ability. As you continue reading through Sartre, see if you can pick up on the difference in Sartre’s use of the knife. How does he relate the knife image to human beings? Why does he think humans are different from knives?

It is precisely the opinions that are most disagreeable to us that we have to do the most to preserve. They are the most in danger of being legally or socially suppressed, and society would be worse off if they were suppressed because our beliefs would become lively and understood.

Because the common consensus is one-sided, we shouldn’t be upset when the minority opinion is biased and one-sided too. What’s more, one-sided people are usually more emphatic and passionate about their belief, so Mill says it’s actually a good thing if the disagreement is expressed in a one-sided way.

Open-mindedness is difficult for people. Usually, we act and think as if what we do is the only way to do things.

Suspending judgment, is refraining from either believing or disbelieving in something. (Suspending judgment on whether God exists is agnosticism.) Mill thinks we sometimes ought to suspend and admit that we don’t have enough information to make a call. Better to admit your ignorance than to hold an opinion without knowing why you hold it.

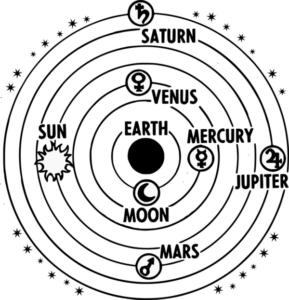

A geocentric model of the solar system has earth at the center; a heliocentric model has the sun at the center. Phlogiston was believed to be a chemical substance playing some of the roles that we now know oxygen plays. Scientists now agree there is no such substance as phlogiston.

To be a ‘rational being’ just means that we humans can reason, we can think critically, imagine possible futures and choose between them, and make arguments. Because we have this unique strength, Mill believes we should use it as much as possible. In the next paragraph, Mill will discuss what it means to use our reason.

Mill is criticizing here people who consider blind faith a virtue, who believe things simply because their god or another authority figure told them they are true, and who cannot give good arguments for why they believe what they believe. This is no way for a rational person to live, he says.

For a defense of blind faith in certain circumstances, see our lesson on Kierkegaard.

Has anyone ever said to you, “If everyone jumped off a cliff, would you jump too?” Mill is making the same argument here. Mill argues that just because all people in your community believe something, that doesn’t make it true. If all people are fallible, then all groups of people are also fallible.

Mill is calling out people here who walk confidently through life with two competing thoughts: “Everybody makes mistakes” and “I’m certain I’m not making a mistake right now.”

Usually, you’re not making a mistake. But those few times when you are making a mistake and you haven’t prepared for it, it blows up in your face.

To call a person infallible is to say they can never be wrong. A fallible person, on the other hand, is sometimes wrong.

Philosophical Jargon: The Ethical

The ethical is the ultimate telos, the ultimate guiding principle of everything in the universe, according to Kierkegaard’s understanding of the dominant ethical paradigm of his time. This essentially means ethics, what is right and wrong, is an objective truth, and our purpose in life is to align ourselves as much as possible with it by doing good things and avoiding bad things.

Philosophical Jargon: Telos

Telos is an Aristotelian term that means an ultimate guiding principle or fundamental purpose engrained in the nature of a thing. Aristotle believed all things, from rocks to human beings, had a telos.

Philosophical Jargon: Subjectivity vs. Objectivity

A subjective truth is one from a particular person’s viewpoint with particular feelings, biases, and predispositions.

This is opposed to “Objectivity,” which is a lack of subjectivity. An objective truth would be true independently of anyone’s perspective on it.

The Greek city of Delphi was the site of a major temple dedicated to the god Apollo. The temple’s high priestess, known as the Pythia, was a famous oracle who played an important role in Greek culture and religious life throughout classical antiquity. By bringing up the God of Delphi, Socrates not only lends divine authority to his life’s mission, but also indirectly rebuts the charge of impiety brought against him.

Socrates here is alluding to the Sophists, professional teachers of rhetoric and debate often hired by wealthy families to help ensure successful political careers for their sons.

St. Thomas Aquinas’ Natural Law Theory centers on the idea that all people are called by God to be and do good while avoiding evil. Further, any rational being should be able to understand and know these obligations of the Natural Moral Law:

“I am the gadfly of the Athenian people, given to them by God, and they will never have another, if they kill me. And now, Athenians, I am not going to argue for my own sake, as you may think, but for yours, that you may not sin against the God by condemning me, who am his gift to you. For if you kill me you will not easily find a successor to me, who, if I may use such a ludicrous figure of speech, am a sort of gadfly, given to the state by God; and the state is a great and noble steed who is tardy in his motions owing to his very size, and requires to be stirred into life. I am that gadfly which God has attached to the state, and all day long 1and in all places am always fastening upon you, arousing and persuading and reproaching you. You will not easily find another like me, and therefore I would advise you to spare me.” –Socrates

Key Point: Dr. King iterates that his motivation for nonviolent protest is to promote healthy tension. Without the friction caused by breaking the status quo of oppression, the door to negotiation will remain closed. King will cite this reason as necessary for any progress and in anticipation to arguments posed by his opposition of religious leaders and passive moderates.

Dr. King makes the appeal to his audience that all people of the world are pieces of a single community of moral concern. This philosophical idea is similar to cosmopolitanism. Derived from the Greek word kosmopolitês (‘citizen of the world’), cosmopolitanism is the idea that all human beings, regardless of their political affiliation, are (or can and should be) citizens in a single community. Different versions of cosmopolitanism focus on political institutions, moral norms, relationships, or shared markets of cultural expression.

April 12, 1963

We the undersigned clergymen are among those who, in January, issued “An Appeal for Law and Order and Common Sense,” in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. We expressed understanding that honest convictions in racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts, but urged that decisions of those courts should in the meantime be peacefully obeyed.

Since that time there had been some evidence of increased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Responsible citizens have undertaken to work on various problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Birmingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and realistic approach to racial problems.

However, we are now confronted by a series of demonstrations by some of our Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders. We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized. But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.

We agree rather with certain local Negro leadership which has called for honest and open negotiation of racial issues in our area. And we believe this kind of facing of issues can best be accomplished by citizens of our own metropolitan area, white and Negro, meeting with their knowledge and experience of the local situation. All of us need to face that responsibility and find proper channels for its accomplishment.

Just as we formerly pointed out that “hatred and violence have no sanction in our religious and political traditions,” we also point out that such actions as incite to hatred and violence, however technically peaceful those actions may be, have not contributed to the resolution of our local problems. We do not believe that these days of new hope are days when extreme measures are justified in Birmingham.

We commend the community as a whole, and the local news media and law enforcement in particular, on the calm manner in which these demonstrations have been handled. We urge the public to continue to show restraint should the demonstrations continue, and the law enforcement official to remain calm and continue to protect our city from violence.

We further strongly urge our own Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations, and to unite locally in working peacefully for a better Birmingham. When rights are consistently denied, a cause should be pressed in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets. We appeal to both our white and Negro citizenry to observe the principles of law and order and common sense.

C. C. J. Carpenter, D.D., LL.D.

Bishop of Alabama

Joseph A. Durick, D.D.

Auxiliary Bishop, Diocese of Mobile, Birmingham

Rabbi Hilton L. Grafman

Temple Emanu-El, Birmingham, Alabama

Bishop Paul Hardin

Bishop of the Alabama-West Florida Conference

Bishop Nolan B. Harmon

Bishop of the North Alabama Conference of the Methodist Church

George M. Murray, D.D., LL.D.

Bishop Coadjutor, Episcopal Diocese of Alabama

Edward V. Ramage

Moderator, Synod of the Alabama Presbyterian Church in the United States

Earl Stallings

Pastor, First Baptist Church, Birmingham, Alabama

Fitz James Stephen was an English lawyer, judge, and writer. For more, see his biography.

Kant claims that we can achieve ‘synthetic a priori knowledge’ of objects in our experience when we understand the ‘conditions of experience’ or what structures our experience. Click here for more on Kant and his ideas.

Reid upholds the ‘common-sense’ view that we can acquire certain knowledge through our observations of the external world. For more on Reid and his ideas, click here.

Descartes holds that we can only be certain of ‘clear and distinct ideas’, and that the truth of these ideas are guaranteed by God’s existence, and the fact that God is not a deceiver. Click here for more on Descartes and his ideas.

Pyrrhonistic Skepticism, introduce by Pyrrho of Elis, is a philosophy which proposes that one should suspend judgment about matters that are ‘non-evident’ (most of them), in order to reach ataraxia – a state of equanimity or peace of mind. For more about this philosophy, click here.

Empiricists claim that we must rely on our observations and experiences of the world to gain knowledge, while Rationalists hold that we can gain knowledge through things like reason. For more on empiricists and rationalists click here.

Ontological means having to do with what exists. Ontology is the study of existence. Do numbers and sets exist in reality or are they just human concepts? Does god exist? Are natural laws part of the fabric of the universe or just useful ways for us to make sense of the world we observe? These are all the kinds of questions that worry philosophers working on ontology.

Glaucon and Socrates both agree that being just and morally good is is instrumentally valuable. If you were unjust, you wouldn’t have friends, you’d lose your job, and you might very well end up in prison—all definitely bad outcomes. The puzzle is, once you have stripped away all of the good things morality gets you (friends, jobs, freedoms), then is there anything left that is good about it?

Socrates was famous for asking those who claimed to have adequate theories of, say, courage or justice, pointed questions designed to show they really did not know what they were talking about. As part of this questioning, Socrates would often emphasize his own ignorance. Hence the term “Socratic irony”: though Socrates claimed to be ignorant, he understood better than his interlocutors how difficult the puzzles were.

Thrasymachus (pronounced Thruh-SIM-ah-kus) is another character in the Republic. He argued earlier in the dialogue that justice is simply another name for whatever those in power desire and that injustice is better than our ordinary conceptions of justice, at least for those who can get away with it.

Examples of Goods that are Both Intrinsic and Instrumental:

These goods can both be enjoyed on their own and tend to get you other goods you want.

These are just good, by themselves, no matter what else you are aiming at.

Examples of Purely Instrumental Goods:

Money – Money is only valuable insofar as it can be traded for other things you want

Being good at standardized testing – Being good at standardized testing only really matters while you are in school.

Knowing how to drive – Knowing how to drive is only good to the extent that you need to drive.

For Kant, a person is an autonomous rational being—someone capable of deciding which rules to follow, planning for the future, and recognizing what their moral obligations are. Someone can be a human organism and not a person, in Kant’s sense. For instance, Kant would not regard someone in a permanent coma as a person.

Kant thinks persons are “ends in themselves”—sources of value that must be respected unconditionally by other rational beings.

For Kant, a mere thing is anything that is not a person—not a being capable of rational autonomy. Mere things can be used as a mere means by rational agents. For example, when I use a shovel to dig a hole, I have no moral duty to respect the shovel. Similarly, we do not owe respect to the animals we use for food.

In this passage, Kant seems to support a Principle of Control for moral responsibility. The Principle of Control holds that you cannot get either moral credit or moral blame for what is outside your control. If you are a well-functioning, autonomous person you can control your decisions about which rules to follow. But none of us have complete control over the consequences of our actions, since there is always some element of luck involved in whether we achieve our plans.

Example 1: Suppose you decide to help out your sick friend by bringing her aspirin. Unbeknownst to you, the medicine has gone bad and is now poisonous. Your friend gets more ill. A defender of the Principle of Control would argue you are not responsible for making your friend sicker, since you could not have known or controlled the outcome. You are just responsible for a good deed—namely, the will to help your friend.

Example 2: Suppose Alex and Bea both have several drinks at a bar one night and decide to drive home. Alex loses control of his car an ends up killing another driver. Bea arrives home safely. By the Principle of Control, both are equally morally blameworthy for their decision to drive drunk. Bea does not get “off the hook” just because she was lucky enough to not harm another person.

Unknown Truths: Knowing something entails believing it. There aren’t precise examples of unknown truths but you might think there is a fact of the matter whether, for instance, there are an even number or an odd number of stars in the Milky Way Galaxy. That fact, whatever it is, is a truth we are not now capable of believing based on any evidence we have.

Well-Justified but False: Sometimes our evidence turns out to be misleading. For example, for many centuries we believed the Earth was the center of the solar system, based on the kinds of observations we were able to make about the movement of the sun and moon. We had reasons for those beliefs, but we were wrong. We eventually got better reasons.

For many decades we believed that fat caused heart disease. Now we have much better evidence that sugar is the culprit.

True but Unjustified: For example, a child might believe she will get money whenever she loses a tooth because she believes the tooth fairy will visit her. The belief is true (most children get money when they lose teeth — at least in the US). But her belief is unjustified — it is her parents leaving the money not a magical fairy.

Or a lottery winner might have believed his ticket would win. His belief turned out to be true, but he had no good reason for believing he’d win a highly random lottery.

A Posteriori: An a posteriori belief is something that you believe on the basis of observations and experience. For instance, you might believe that it is cold in your room right now. Or that your room was cold yesterday. Or that this screen is white and black.

A Priori: An a priori belief is something that you believe without making observations out in the world (you believe it prior to making observations). For instance, you might think mathematical facts are known a priori — you know that 1+1=2 without performing any experiments. You might also know that you are thinking or that you have a headache a priori. Some a priori beliefs are called intuitions — beliefs that simply occur to us as true. For example, you might have a moral intuition that is wrong to kick puppies.

Premise 1: A necessary condition for being a sandwich is having two or more slices of bread.

Premise 2: Burritos have one and only one tortilla shell.

(C) Not a sandwich.

But what about chalupas?

Aristotle famously claims that there are no general moral theories that will always guide you in figuring out what’s right and wrong. For Aristotle, determining what’s right or good (what a virtuous person would do) always depends on the particulars of the case. Hence, learning to live well is more like learning to diagnose diseases, and less like learning to solve equations.

Aristotle contrasts natural properties and those acquired by habit. The key idea here is that properties things have by nature cannot be changed, but those that we acquire by habit can be changed (for instance, by training ourselves in a different way).

Example: I naturally have the property of being alive. I could acquire (through training and practice) the property of being able to speak Japanese.

An instrumental end or goal is one you pursue in order to get closer to another end or goal. For instance, you might pursue studying for the SATs because you are pursuing the more important goal of attending college. But why are you attending college? Presumably that is also an instrumental end: you are attending college so you can get a good job, learn about subjects you are interested in, and make friends.

Aristotle thinks a final end or goal is one for which we cannot reasonably wonder anymore why we are pursuing it. We are pursuing it for its own sake.

Presumably all instrumental ends have a final end at the end of the chain.

Take SATs. –> Go to college. –> Get a great job. –> Make money. –> Be Happy. –> ? If nothing comes next, this is the final end.