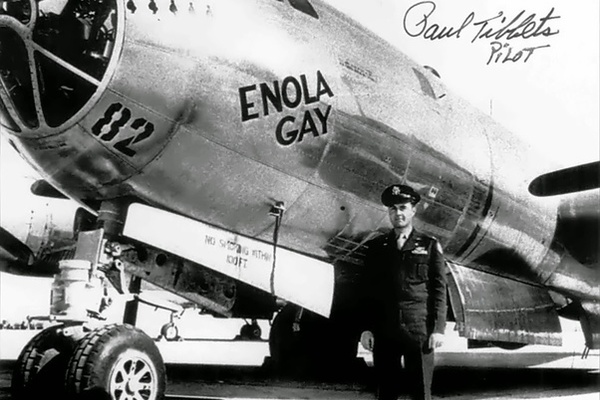

When making moral decisions, is it better to focus on the particulars of the case (like the names, histories, and motives of individuals involved) or to abstract to broader categories (like how much pleasure or suffering will result)? How important is it to have good intentions rather than to be the cause of the best results? In this class period, we will consider what it means to intentionally take responsibility for a moral decision, looking at ideas from contemporary virtue ethicist Elizabeth Anscombe. We’ll discuss the concepts of moral injury and apply Anscombe’s theory to debates about the ethics of violence — in particular looking at a case study of President Truman’s decision to detonate atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And we will work on the skill of telling stories that uncover morally important intentions.

We have three main learning goals for this day. You will:

- Understand the key differences between how consequentialists and virtue ethicists approach questions of personal responsibility

- Appreciate the role narrative, or telling “morally thick” stories, plays in Anscombe’s theory of responsibility

- Practice telling your own morally thick stories about things you’d like to take responsibility for in the story of your life.

Read This:

Primary: Selections from Anscombe’s “Intention” and “Mr. Truman’s Degree” (Interactive Essay)

Secondary: Assessing Intentions: Can the Powerless be Good?

Do This:

Required:

- Make sure you’ve completed the “How We Argue” (ThinkerAnalytix) course up through lesson 2 by today’s class.

- After you’ve finished today’s reading, make sure you complete the reading quiz, which you can access through your section’s Canvas page.

Suggested: In our experience, college courses go best when you bring your “whole self” into the material. If you haven’t done this before, consider setting a timer for five minutes to sit back, look over your notes, and just think about how today’s class and content relates to questions you bring to the table, or issues you care deeply about.

In class, your professor will be presenting some material (and making sure you understood what you read), but lessons can be shaped deeply by questions or comments you bring in. Don’t be afraid to raise your hand (or come up before or after class) to raise these sorts of things. You’ve got a lot of agency in God and the Good Life, and — if you use it — you and your classmates (and your instructor and TAs) will be grateful for it!

This is the last time this suggestion ^ will appear on the course webpage, but we hope you’ll keep it in mind for the rest of the semester!