Finding Meaning in Suffering: Post-Holocaust Theology

Introduction to Post-Holocaust Theology

Introduction to Post-Holocaust Theology

-

What is Post-Holocaust Theology?

-

Post-Holocaust Theology and the Problem of Evil

The Holocaust was “the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime” during World War II. It was a deeply traumatic event that shook the core of many theists. This absurdly evil act posed major problems for theologians across the world, particularly Jews. The tragedy understandably raised questions about the existence of God and the core tenets of Judaism. In the decades following World War II, questions of faith and ethics in a post-Holocaust world enveloped synagogues, Jewish homes, and the minds of Jewish scholars. These difficulties are even documented during the Holocaust itself. In Night, Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel recounts a rabbi in the concentration camp who stated the following:

“It’s over. God is no longer with us…I’m a simple creature of flesh and bone. I suffer hell in my soul and my flesh. I also have eyes and I see what is being done here. Where is God’s mercy? Where’s God? How can I believe, how can anyone believe in this God of Mercy?”

Constructing a response to the Holocaust is important for Jews and theologians who still seek to live a religious life after this dreadful event. The answer comes in the form of post-Holocaust theology, a philosophy within Judaism that provides a pathway for Jews and others disturbed by the Holocaust to understand the Holocaust and live a meaningful life. It is the answer to the most well-known example of the problem of evil.

In this digital essay, we will learn about the three major principles of post-Holocaust theology. Please note that this digital essay is not a comprehensive look at post-Holocaust theology. The discipline involves a wide variety of viewpoints and these principles are common elements within the literature that are relevant to our course. If you’re interested in learning more, we encourage you to research the topic further.

As you may recall from the “God and Suffering: Fyodor Dostoyevsky” digital essay, a particularly strong argument against the existence of God is the problem of evil. The Holocaust would seem as an apt example for the argument, making it an important topic for theists to unravel. The implications of the Holocaust for the problem of evil become more apparent through the Jewish conception of God. Jews believe that God brings judgement, but his divine judgement is just and tempered by mercy. In fact, God is defined by his interventions to protect his people, such as delivering the Israelites from slavery in Egypt (Exodus 20:2).

If God rewards the righteous and punishes the wicked, what does that say about the Holocaust? Joel Teitelbaum, a Hassidic Jewish rabbi and Holocaust survivor, believed that the Holocaust was a divine punishment for the sins of the Jewish people. Richard Rubenstein was a Jewish theologian and post-Holocaust scholar who argued in After Auschwitz that the only rational response to the Holocaust is to reject God’s existence and that all existence is ultimately meaningless. He endorsed an existentialist view, where humans define meaning for themselves. Later on in his life, Rubenstein clarified his view, explaining that belief in God is still rational but that our culture is one defined by the “death of God.” In this setting, while God may exist, humanity treats God as if he does not exist, instead allowing individuals to create their own meaning.

Although negative reactions to God, such as denying his existence, are present in post-Holocaust theology, the views of Teitelbaum, Rubenstein, and others like them are largely rejected by Jews and the broader theological community. David Weiss Halvini, a Holocaust survivor and Jewish scholar, summarizes the shortcomings of these views in “Prayer in the Shoah”:

What happened in the Shoah is above and beyond measure, above and beyond suffering, above and beyond any punishment. There is no transgression that merits such punishment. Such utter destruction has never transpired before in history, has never before been fashioned by Satan, and it cannot be attributed to sin…Such a person [who attributes the Shoah to the Jews’ sins] not only accuses the sufferers slanderously with having caused their own suffering, but also indirectly belittles the guilt of the truly guilty by implying that they only did what they had to do. If not they, then some others would have had to do this. Such things must not be uttered!

It simply did not make sense to approach this catastrophic event in a gloomy, depressing conclusion. In a way, such a finding undermines and diminishes the lives of those who suffered. After such a tragic event, there must be something to glean from it; otherwise, the unnecessary suffering was worthless and a similar disaster can occur.

Key Principle

God is Hidden

God is Hidden

-

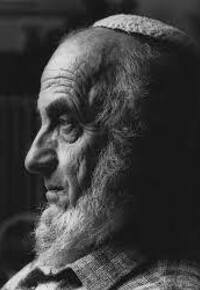

Abraham Joshua Heschel

-

Humanity Exiled God

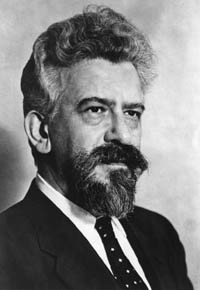

Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-1972), a Polish-born American rabbi, was a leading theologian and philosopher of the Jewish tradition in the 20th century. A Holocaust survivor, his work had a profound effect on Judaism by capturing a succinct interpretation of post-Holocaust theology. While Heschel was a respected scholar in academia, his main interest lied in exploring spirituality. He believed that the call of the prophets in the Hebrew Bible was one of social justice, leading him to be a fierce advocate of the Civil Rights Movement and critic of the Vietnam War.

Argument

Humanity Rejected God

Humanity Rejected God

-

Humanity Silenced God

-

Humanity Silenced God Argument Outline

Man is Not Alone, one of Heschel’s quintessential works, explores the view of humanity pushing God away. As you read an excerpt from the book, consider whether a Holocaust victim would agree to this explanation during the tragic event.

For us, contemporaries and survivors of history’s most terrible horrors, it is impossible to meditate about the compassion of God without asking: Where is God?

The major folly of this view seems to lie in its shifting the responsibility for man’s plight from man to God. Rather than admit our own guilt, we seek to shift the blame upon someone else. For generations we have been investing life with ugliness and now we wonder why we do not succeed. God was thought of as a watchman hired to prevent us from using our loaded guns. Having failed us in this, He is now thought of as the ultimate Scapegoat.

We live in an age when most of us have ceased to be shocked by the increasing breakdown in moral inhibitions. The decay of conscience fills the air with a pungent smell. Good and evil, which were once as distinguishable as day and night. have become a blurred mist. But that mist is man-made. God is not silent. He has been silenced.

We have trifled with the name of God. We have taken ideals in vain, preached and eluded Him, praised and defied Him. Now we reap the fruits of failure. Through centuries His voice cried in the wilderness. How skillfully it was trapped and imprisoned in the temples! How thoroughly distorted! Now we behold how it gradually withdraws,abandoning one people after another, departing from their souls, despising their wisdom. The taste for goodness has all but gone from the earth.

Man was the first to hide himself from God, after having eaten of the forbidden fruit, and is still hiding. The will of God is to be here, manifest and near; but when the doors of this world are slammed on Him. His truth betrayed, His will defied, He withdraws, leaving man to himself. God did nor depart of own volition; He was expelled. God is in exile.

The prophets do not speak of the hidden God but of the hiding God. His hiding is a function not His essence, an act not a permanent state. It is when the people forsake Him, breaking the Covenant which He has made with them. that He forsakes them and hides His face from them.’ It is not God who is obscure. It is man who conceals Him. His hiding from us is not in His essence: “Verily Thou art a God that hidest Thyself, O God of Israel, the Saviour!” (Isaiah 45:15). A hiding God, not a hidden God. He is waiting to be disclosed, to be admitted into our lives.

In the excerpt, Heschel is attempting to convey that it is not God who abandoned humanity, but humanity who abandoned God. He reasons that humanity’s inclination to engage in sinful activities that draw one away from God has led to the silencing of God. Heschel believes that the actualization of God’s presence in the world is through people believing in God and following His will. When that does not occur, God has no stake in reality and is blocked from humanity. At a basic level, the issue is that God is speaking to the brick wall that is humanity. Because humanity never listens, God is effectively silenced and ignored. His argument is broken down below.

(1) God exists among humanity when people believe in Him, pray to Him, and follow His will.

Example: One would certainly say that God exists among a religious community in the sense that members of that community believe in God and actively participate in society as if God exists.

(2) God cannot exist within a community that does not believe in Him or follow His will.

Example: A predominantly secular community would lack God’s presence and influence in daily life because He does not play an important role in that community.

(3) Humanity has continually ignored God, engaging in vices and sinful activity contrary to God’s teachings.

Example: Human history’s long strain of unnecessary suffering, conflict, and vice demonstrates the human inclination to engage in activities that are not in accordance with God’s will.

(4) The fault of an action lies in its instigator, not the one who is affected by that action.

Example: If Joe throws a football that hits Henry in the face, Henry is not at fault. Joe deserves blame because it was his actions that caused the football to harm Henry.

(C) Humanity is responsible for God’s absence.

Connection

The Free Will Defense

The Free Will Defense

-

Eliezer Berkovits

-

The Consequences of Free Will

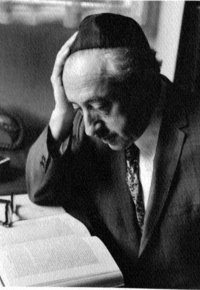

Eliezer Berkovits (1908-1992) was also a renowned rabbi, theologian, and educator in the 20th century. Similar to Heschel, Berkovits was interested in the relationship between humanity and God, specifically in transcending events like the giving of the Torah by God to the Israelites on Mount Sinai. He was enthralled by the role of piety in this relationship and how individuals can grow closer to God through good actions. Understandably, Berkovits was perplexed by the seeming absence of God during the Holocaust, a question he explored in Faith After the Holocaust.

Berkovits complements Heschel’s view with the free will defense that you may remember from the Dostoyevsky digital essay. In Faith After the Holocaust, Berkovits reasons that God’s respect of humanity’s free will necessitated the Holocaust to occur. The ability for humans to express autonomy and dominion over the world endows a responsibility to care for the world and others. Humanity has the potential to fulfill or fail to uphold that responsibility, with the latter being the price of free will.

Argument

Free Will

In Faith After the Holocaust, Berkovits approaches the inquiry of providing an explanation for why God would permit the Holocaust. He provides a defense based on free will, arguing that God granting humanity free will necessitates that evil be permitted in the world. To accomplish this task, he must contend with the explanations of the Holocaust we discussed earlier that place the blame on humanity’s sins. Consider his argument below.

In biblical terminology, we speak of Hester Panim, the Hiding of the Face, God’s hiding of his countenance from the sufferer. Man seeks God in his tribulation but cannot find him. It is, however, seldom realized that “The Hiding of the Face” has two meanings in the Bible, which are no way related to each other. It is generally assumed that the expression signifies divine judgement and punishment. We find it indicated, for instance, in Deuteronomy, 31:17-18, in the words:

“Then My anger shall be kindled against them on that day, and I will forsake them, and I will hide My face from them. And they shall be devoured, and many evils and troubles shall come upon them…And I will surely hide My face on that day for all the evil which they shall have wrought, in that they are turned unto other gods.”

But the Bible also speaks of the Hiding of the Face when human suffering results, not from divine judgment, but from the evil perpetrated by man. Even the innocent may feel himself forsaken because of the Hiding of the Face. A moving example of this form of Hester Panim is the Forty-Fourth Psalm, from which we have already quoted a short passage:

All this is come upon us: yet have we not forgotten Thee,

Neither have we been false to Thy covenant.

Our heart is not turned back.

Neither have our steps declined from Thy path;

Though Thou hast crushed us into a place of jackals,

And covered us with the shadow of death.

If we had forgotten the name of our God,

Or spread forth our hands to a strange god;

Would not God search this out?

For he knoweth the secrets of the heart.

Nay, but for Thy sake are we killed all the day;

We are accounted as sheep for the slaughter.

Awake, why steepest Thou, O Lord?

Arouse Thyself, cast not off for ever

Wherefore hidest Thou Thy face,

And forgettest our affliction and our oppression?

For our soul is bowed down to the dust;

Our belly cleaveth to the earth.

Arise for our help.

And redeem us for Thy mercy’s sake.

The Hiding of the Face about which the psalmist complains is altogether different from its meaning in Deuteronomy. There it is a manifestation of divine anger and judgment over the wicked. Here it is indifference—God seems to be unconcernedly asleep during the tribulations inflicted by man on his fellow. Of the first kind of Hester Panim one might say that it is due to Mipnei Hataeinu, that it is judgement because of sins committed, but not of the second kind. It is God hiding himself mysteriously from the cry of the innocent.

Argument

Evaluating the Free Will Argument

Evaluating the Free Will Argument

-

Free Will Argument Outline

-

Free Will and the Problem of Evil

In the text above, Berkovits contends with two possible interpretations of God’s silence during the Holocaust based on the concept of Hester Panim. Either God was punishing the Jews for some sin they committed, or a higher obligation stopped him from preventing the Holocaust. Berkovits rejects the former explanation, as there is no evidence of God’s anger or disappointment towards the Jews, a condition that was noted many times when the Jews were punished in the Torah. Instead, he argues that God’s silence is simply that; it is a lack of participation in human affairs out of respect for humanity’s free will. If God were to interfere in humanity’s problems, it would undermine that free will. His argument is broken down below.

(1) God permits evil either because He is angry at humanity and allows suffering as a punishment, or God restrains Himself from interfering to enable human free will.

Example: In the Torah, God punished the Israelites for breaking the covenant and sinning against God by allowing the Babylonians to conquer Israel and exiling Jews away from the promised land. In that way, suffering was a punishment for angering God. On the other hand, as Psalm 44 indicates in the text above, there are some punishments that were not given out of anger. Sometimes, there may be no clear explanation for evil other than free will.

(2) There is no identifiable offense by the Jewish people that would warrant God’s anger and permit such a devastating event like the Holocaust.

Example: There is no action committed by the Jews in history that could seemingly justify the killing of six million Jews, as noted earlier in the digital essay.

(3) The first possible explanation for the Holocaust must be rejected.

Example: If no sinful action of equal magnitude to the Holocaust can be found, there is no rational basis to presume God is angry.

(4) There must be an explanation for all events.

Example: The events of human history are interconnected and act very closely in a cause-effect relationship. For instance, Germany’s loss in World War I and the severe conditions placed on the country by the Treaty of Versailles gave rise to poor economic conditions in Germany that Hitler capitalized on in his rise to power, leading to World War II and the Holocaust.

(C) God permitted the Holocaust to respect human free will.

In the “God and Suffering: Fyodor Dostoyevsky” digital essay, we watched Rabbi Jonathan Sacks deliver the common version of the free will response to the problem of evil. Rabbi Sacks (1948-2020) was a British rabbi who served as Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth from 1991 to 2013. His work as a philosopher and theologian had a great influence on post-Holocaust theology thus far in the 21st century, especially in explaining the Holocaust’s significance to a general audience. In the video below, notice how Sacks invokes the themes of free will and God’s exile to explain God’s absence during the Holocaust. As you rewatch Rabbi Sacks’s response, note any new insights you may have after learning about Heschel’s understanding of the Holocaust and Berkovits’s articulation of the free will defense.

Connection

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks: Finding God in the Holocaust

In another video, Rabbi Sacks delivers an interesting view of the Holocaust from a modern lens. As you watch his remarks, take note of any similarities or differences between Rabbi Sacks’s view and that of Heschel and Berkovits. How do you see the different interpretations of the Holocaust influence modern conceptions of post-Holocaust theology? Do you agree with his interpretation?

Key Principle

Evil Cannot be Rationalized

Evil Cannot be Rationalized

-

Arthur Cohen

-

Thinking the Tremendum

Arthur Cohen (1928-1986) was a Jewish-American theologian, author, and scholar. He was considered an expert on modern European literature, medieval Jewish mysticism, the history of Dada and surrealism, and modern typography and design. He studied for some time under Martin Buber, another Jewish philosopher who emphasized dialogue and existentialism in his work. The Holocaust was a central topic of Cohen’s work as he spent decades studying Jewish thought and theology. His views on the Holocaust can be summarized in four parts: 1) the Holocaust is unique and therefore has theological consequences particular to itself that are unconnected to other events, 2) human thought cannot comprehend the full extent of the horrors committed during the Holocaust, 3) there is no inherent meaning to genocide, and 4) evil is more real and humanity is more capable of committing mass atrocities than previously thought.

Cohen’s thoughts on the Holocaust are contained in his book The Tremendum: A Theological Interpretation of the Holocaust. In it, Cohen is concerned with the reality of evil, God’s existence, and human free will in light of the Holocaust. Part of his conclusion is that an event like the Holocaust requires a fundamental revision in humanity’s conception of God. He does not blame God for the Holocaust, but believes that God’s relationship with humanity must be reinterpreted to better understand why such a horrific evil was permitted. Similar to Berkovits, Cohen emphasizes God’s respect for human free will as a possible explanation, but is not fully satisfied.

Cohen’s work brings us to the second principle of post-Holocaust theology that we will discuss, which is that evil cannot be rationalized. In The Tremendum, Cohen emphasized that there is no basis for rationalizing the Holocaust and the horrors committed by the Nazis. Any attempt to articulate reasoning behind the event undermines the suffering of Holocaust victims while being an affront to rationality itself. We can expand this interpretation to the broader notion of evil and suffering in the world to argue that there is no rational basis for evil actions. Suffering can never be justified because it contradicts the notions of human dignity and freedom that we cherish in society.

Argument

The Holocaust is not Rational

An important component of post-Holocaust theology is grappling with understanding the actions and motivations of the Nazis. Even as the maintenance of concentration camps threatened Germany’s sustainability and chances to win World War II, the Nazis continued to increase their crimes against humanity to unthinkable levels. Why was this so? What was their reasoning? Post-Holocaust theologians like Arthur Cohen argue that there is no reasoning. Cohen suggests that the events of the Holocaust occur outside the standards of rationality. According to him, there is no rationalizing the Holocaust. As you read an excerpt from “Thinking the Tremendum,” a chapter from The Tremendum, consider how an individual could justify committing an action like the Holocaust without a rational explanation.

Whatever we may learn from history, moral philosophy, psychopathology, or political science about the conditions which preceded and promoted the death camps, or the behavior of oppressors and victims which obtained within the death camps, is unavailing. All analysis holds us within the normative kingdom of reason, and however the palpable irrationality of the events, the employment of rational analysis is inappropriate. I do not feel the calm of reason to be obscene as some critics of the rational inquiry into the tremendum have described it. It is not obscene for human beings to try to retain their sanity before an event which disorders sanity. It is a decent and plausible undertaking. It is simply inappropriate and unavailing. Probative inquiry and dispassionate reason have no place in the consideration of the death camps, precisely because reason possesses a moral vector. To reason, that is to estimate and evaluate, is to employ discernment and discrimination before a moral ambiguity. The tremendum is beyond the discourse of morality and rational condemnation. It is not that the death camps were absolutely evil. Such judgments do not help. It is not enough to pronounce them absolutely evil. Absolute evil is a paradigm. There is nothing to which we can point in the history of men and nations which is absolutely evil, although the criterion of that abstraction has helped moralists to pronounce upon the relative evils of history.

Absolute evil – even if it designated something real – would be an inept formulation, for what does it mean, in fact, to say of some thing or event that it is absolutely evil? It means only that we can conceive of no greater evil, whereas in truth we can: we can conceive of a system that can murder all life (assuming, of course, that abundant life is an absolute good), but clearly this adds nothing to our absolute but exaggeration. We look for qualitative enrichment of our moral sensibility, a texturing and refinement, while all our language before the event presses us to grosser and more extreme formulations.

The relativity of evil in the deliberations of moralists rarely entails the exposition of the relative good. Relative evils do not complete themselves by the description of relative goods. Relative evil is measured in the mind against absolute evil. Of course, such a logic of moral experience has an ultimate reckoning. If it is commonplace for human beings to free themselves from the paradigm of the absolute, it becomes ever easier to ignore or to excuse transgression. Human beings learn to rationalize and justify so artfully and so well that the right time passes unobserved, when they should have shouted ‘no, not this, not this.’ But, of course, it is hard in a shouting and busy world, continuously assaulted by interests and needs, for any single human being to be heard warning against evil. During such times, the recognition that there are indeed absolute evils (even though abstractly described) has not prevented us from accumulating a mountain of small evils which, like the bricks of the Tower of Babel, might one day reach up and pierce the heavens. The point of this is to suggest that moral convention, a pragmatic regimen of norms and regulations of behavior retain their authority only so long as the absolute evil of which they are special and modest exempla remains abstract and unrealized. When absolute evil ceases, however, to be the abstract warning of the impending and possible and comes to be, how shall the descriptive domains of the moral and immoral retain their authority?

If this analysis is correct, it will be readily understood why I have come to regard the death camps as a new event, one severed from connection with the traditional presuppositions of history, psychology, politics, and morality. Anything which we might have known before the tremendum of this event is rendered conditional by its utterness and extremity. Note that I have not referred to Auschwitz as the name by which to concretize and transmit the reality of the tremendum. Auschwitz was only one among many sites of death. It was not even the largest death camp, although it may well have claimed the largest number of victims. Auschwitz is a particularity, a name, a specific. Auschwitz is the German name for a Polish name. It is a name which belongs to them. It is not a name which commemorates. It is both specific and other.

Argument

The Holocaust is not Rational Argument Outline

Cohen provides two conclusions from his analysis on the Holocaust. First, there is no method of rationality that could justify the Holocaust because the Holocaust has no moral component. This rests on Cohen’s notion that rationality and morality are intertwined. Second, the Holocaust introduced absolute evil to the world, delegitimizing any justification for relative evils because they can no longer appeal to the notion of an impossible absolute evil. This means that no evil in the world can be justified on rational grounds. His argument is broken down below.

(1) Rationality involves some end towards a final good.

Example: Any kind of action that can be justified on rational grounds has the goal of some end that yields a form of goodness. For instance, Julia’s goal of attending law school is based on her passion for justice, which can be viewed as a good.

(2) Morality provides the basis for identifying a final good.

Example: We use morality to recognize final goods, as any philosophy we have discussed in this course uses some account of morality to identify an ultimate end of goodness. For instance, virtue ethics would identify the achievement of eudaimonia through the cultivation of virtue as the moral pathway to the good.

(3) Rationality requires an appeal to morality.

Example: Julia’s goal of attending law school must have some conclusion towards a final end, which we have noted is a passion for justice. However, while that may appear rational, there must be some further goal that provides a motivation for pursuing that action. Morality fills that gap, as it can identify Julia’s interest in protecting marginalized groups as her motivation to pursue justice. In this way, rationaltiy and morality are intertwined.

(4) The Holocaust has no moral appeal.

Example: There is no legitimate concept of morality that could possibly justify the tragedy of the Holocaust.

(5) The Holocaust is not rational.

Example: If we cannot identify a moral appeal for the Holocaust, it cannot be rationalized.

(6) The evil grounded in the Holocaust can be analogous to the evils of other kinds of suffering.

Example: The motivation of the Holocaust to persecute and discriminate a group of people is a common phenomenon for many kinds of suffering in human history.

(C) Evil cannot be rationalized.

Connection

The Moral Shudder

The Moral Shudder

-

Emil Fackenheim

-

The Ought Not

Another notable scholar on this topic is Emil Fackenheim (1916-2003). Fackenheim was a Jewish philosopher and rabbi who was widely understood as an expert on the theological implications of the Holocaust. In his work, he was concerned with the meaning of Judaism after the Holocaust and how Jews can still be Jews after such a devastating event. Fackenheim argued that a horrible event like the Holocaust denotes the responsibility of Jews to actively pursue their survival through community-building in times of persecution.

In To Mend the World: Foundations of Post-Holocaust Jewish Thought, Fackenheim takes Cohen’s sentiment a step further in describing the effects of attempting to rationalize a non-rationalizable event. Cohen reasons that such an action leads one to “shudder” that yields feelings of antagonism towards perpetrators of the Holocaust. It leads to the conclusion that such an event “ought not” happen because it is irrational. This leads Fackenheim to the “resisting victim,” a term he uses to describe the urge of oneself to resist reasoning a horrible event like the Holocaust in any way. It causes one to pursue justice for victims. Read an excerpt from Fackenheim’s text below.

This [The Holocaust] chills the marrow and numbs the mind. It also haunts it. The philosophical mind must resist the temptation to evade the haunting fact but must rather let itself be haunted. Thought, in short, moves in a circle.

The limit of philosophical intelligibility, however, is not quite yet the end of philosophical thought. The circular thought-movement that fails produces a result in its very failure, for it grasps, to the extent possible, a whole. On our part, we confront in the Holocaust world a whole of horror. We cannot comprehend it but only comprehend its incomprehensibility. We cannot transcend it but only be struck by the brutal truth that it cannot be transcended. Here the very attempt to see a meaning, or do a placing-in-perspective, would already constitute a dissipation, not only blasphemous but also untruthful and hence unphilosophical, of either the whole of horror-the fact that it was not random, piecemeal, accidental, but rather integrated into a world-or else of the horror of the whole-the fact that the whole possessed no rational, let alone redeeming purpose subserved by the horror, but that the horror was starkly ultimate.

The philosopher may feel – he believes that nothing human is alien to him – that its whole is not unintelligible after all. He wants to understand Eichmann and Himmler, for he wants to understand Auschwitz. And he wants to understand Auschwitz, for he wants to understand Eichmann and Himmler. Thus his understanding gets inside them and their world, bold enough not to be stopped even by Eichmann’s smirk and Himmler’s gloves. To get inside them is to get inside the ideas behind the smirk and the gloves; and whereas this is not necessarily to accept these ideas it is in any case to obtain a kind of empathy. And thus it comes to pass, little by little, that a philosopher’s comprehension of the Holocaust whole-of-horror turns into a surrender, for which the horror has vanished horn the whole and the Unwelt has become a Welt like any other. In this way, one obtains a glimpse of the Ph.D.s among the murderers, and shudders.

The truth disclosed in this shudder is that to grasp the Holocaust whole-of-horror is not to comprehend or transcend it, but rather to say no to it, or resist it. The Holocaust whole of horror is (for it has been); but it ought not to be (and not to have been). It ought not to be (and have been), but it is (for it has been). Thought would lapse into escapism if it held fast to the “ought not” alone; and it would lapse into paralyzed impotence if it confronted, nakedly, the devastating “is” alone. Only by holding fast at once to the “Is” and “ought not” can thought achieve an authentic survival. Thought, that is, must take the form of resistance.

This resistance-of-thought, however, cannot remain self-enclosed in thought. The tension between the “is” and the “ought not”-the more unendurable to philosophical thought, the deeper, the more rational, the more philosophical it is-would lose all depth and seriousness if the resulting no were confined to thought alone. Having reached a limit, resisting thought must point beyond the sphere of thought altogether, to a resistance which is not in “mere” thought but rather in overt, fresh-and-blood action and life.

Key Principle

Tikkun Olam: “Repair of the World”

Tikkun Olam: “Repair of the World”

-

Tikkun Olam

-

The 614th Commandment

The third principle of post-Holocaust theology we will discuss is tikkun olam, the Hebrew phrase meaning “repair of the world.” Following the Holocaust, many people were struck at the utter devastation brought upon the world by World War II. Rather than allow catastrophe to drown humanity in sorrow, many reversed this downward spiral by emphasizing the pursuit of a more just world. For instance, many Holocaust survivors went on to do social work, rebuilding society from the ashes World War II left behind. This idea is enveloped by tikkun olam, which emphasizes the communal struggle for a better world.

Fackenheim articulates this notion specifically within the context of the Holocaust in “The 614th Commandment,” a lecture he delivered at “Jewish Values in the Post-Holocaust Future: A symposium” in 1967. In it, Fackenheim argues that the only proper response to the Holocaust is the adoption of a new commandment alongside the 613 commandments already written in the Torah, the holy book of the Jewish people. He reasons that Jewish tradition could not have anticipated the Holocaust, so change must occur to prevent another Holocaust from happening. This 614th commandment is that “Thou shalt not hand Hitler posthumous victories. To despair of the God of Israel is to continue Hitler’s work for him.” The commandment insists that the Jewish people actively work to produce a world in which an event like the Holocaust can never happen again. In other words, Jews must pursue a more just world. Read Fackenheim’s argument below.

The implications of even so slender a bond are momentous. If the 614th commandment is binding upon the authentic Jew, then we are, first, commanded to survive as Jews, lest the Jewish people perish. We are commanded, second, to remember in our very guts and bones the martyrs of the Holocaust, lest their memory perish. We are forbidden, thirdly, to deny or despair of God, however much we may have to contend with Him or with belief in Him, lest Judaism perish. We are forbidden, finally, to despair of the world as the place which is to become the kingdom of God, lest we help make it a meaningless place in which God is dead or irrelevant and everything is permitted. To abandon any of these imperatives, in response to Hider s victory at Auschwitz, would be to hand him yet other, posthumous victories.

How can we possibly obey these imperatives? To do so requires the endurance of intolerable contradictions. Such endurance cannot but bespeak an as yet unutterable faith. If we are capable of this endurance, then the faith implicit in it may well be of historic consequence. At least twice before—at the time of the destruction of the First and of the Second Temples—Jewish endurance in the midst of catastrophe helped transform the world. We cannot know the future, if only because the present is without precedent. But this ignorance on our part can have no effect on our present action. The uncertainty of what will be may not shake our certainty of what we must do.

A commitment. In the present situation, this question becomes: can we confront the Holocaust, and yet not despair? Not accidentally has it taken twenty years for us to face this question, and it is not certain that we can face it yet. The contradiction is too staggering, and every authentic escape is barred. We are bidden to turn present and future life into death, as the price of remembering death at Auschwitz. And we are forbidden to affirm present and future life, as the price of forgetting Auschwitz.

We have lived in this contradiction for twenty years without being able to face it. Unless I am mistaken, we are now beginning to face it, however fragmentarily and inconclusively. And from this beginning confrontation there emerges what I will boldly term a 614th commandment: the authentic Jew of today is forbidden to hand Hitler yet another, posthumous victory. (This formulation is terribly inadequate, yet I am forced to use it until one more adequate is found. First, although no anti-Orthodox implication is intended, as though the 613 commandments stood necessarily in need of change, we must face the fact that something radically new has happened. Second, although the commandment should be positive rather than negative, we must face the fact that Hitler did win at least one victory—the murder of six million Jews. Third, although the very name of Hitler should be erased rather than remembered, we cannot disguise the uniqueness of his evil under a comfortable generality, such as persecution-in-general, tyranny-in-general, or even the-demonic-in-general.)

I think the authentic Jew of today is beginning to hear the 614th commandment. And he hears it whether, as agnostic, he hears no more, or whether, as believer, he hears the voice of the metzaveh (the commander) in the mitzvah (the commandment). Moreover, it may well be the case that the authentic Jewish agnostic and the authentic Jewish believer are closer today than at any previous time.

To be sure, the agnostic hears no more than the mitzvah. Yet if he is Jewishly authentic, he cannot but face the fragmentariness of his hearing. He cannot, like agnostics and atheists all around him, regard this mitzvah as the product of self-sufficient human reason, realizing itself in an ever-advancing history of autonomous human enlightenment. The 614th commandment must be, to him, an abrupt and absolute given, revealed in the midst of total catastrophe.

Argument

The Return of God

Heschel also describes this phenomenon, although without mentioning the Holocaust. In God in Search of Man, he argues that following in the ways of God will yield a better world that is holier and more just. In this way, God returns to humanity. Read Heschel’s argument below.

How does the world look in the eyes of God? Are we ever told that the Lord saw that the righteousness of man was great in the earth, and that He was glad to have made man on the earth? The general tone of the biblical view of history is set after the first ten generations: “The Lord saw how great was man’s wickedness on earth, and how every plan devised by his mind was nothing but evil all the time. And the Lord regretted that He had made man on earth, and His heart was saddened” (Genesis 6:5-6; cf. 8:21). One great cry resounds throughout the Bible: The wickedness of man is great on the earth.

More frustrating than the fact that evil is real, mighty, and tempting is the fact that it thrives so well in the disguise of the good, and that it can draw its nutriment from the life of the holy. In this world, it seems, the holy and the unholy do not exist apart but are mixed, interrelated, and confounded; it is a world where idols are at home, and where even the worship of God may be alloyed with the worship of idols.

God asks for the heart, yet our greatest failure is in the heart. “The heart is deceitful above all things, it is exceedingly weak–who can know it?” (Jeremiah 17:9). The regard for the ego permeates all our thinking. Is it ever possible to disentangle oneself from the intricate plexus of self-interest? Indeed, the demand to serve God in purity, selflessly, “for His sake,” on the one hand, and the realization of our inability to detach ourselves from vested interests, represent the tragic tension in the life of piety. In this sense, not only our evil deeds, but even our good deeds precipitate a problem.

What is our situation in trying to carry out the will of God? In addition to our being uncertain of whether our motivation – prior to the act – is pure, we are continually embarrassed during the act with “alien thoughts” which taint our consciousness with selfish intentions. And even following the act there is the danger of self-righteousness, vanity, and the sense of superiority, derived from what are supposed to be acts of dedication to God.

In the face of so much evil and suffering, of countless examples of failure to live up to the will of God, in a world where His will is defied, where His kingship is denied, who can fail to see the discrepancy between the world and the will of God?

And yet, just because of the realization of the power of evil, life in this world assumed unique significance and worth. Evil is not only a threat; it is also a challenge. It is precisely because of the task of fighting evil that life in this world is so preciously significant.

All of history is a sphere where good is mixed with evil. The supreme task of man, his share in redeeming the work of creation, consists in an effort to separate good from evil and evil from good.

This is what the prophets discovered: History is a nightmare. There are more scandals, more acts of corruption, than are dreamed of in philosophy. It would be blasphemous to believe that what we witness is the end of God’s creation. It is an act of evil to accept the state of evil as either inevitable or final. Others may be satisfied with improvement; the prophets insist upon redemption. The way man acts is a disgrace, and it must not go on forever.

The climax of our hopes is the establishment of the kingship of God, and a passion for its realization must permeate all our thoughts. For the ultimate concern of the Jew is not personal salvation but universal redemption. Redemption is not an event that will take place all at once at “the end of days” but a process that goes on all the time. Man’s good deeds are single acts in the long drama of redemption, and every deed counts. One must live as if the redemption of all men depended upon the devotion of one’s own life.

At the end of days, evil will be conquered by the One; in historic times evils must be conquered one by one

Argument

The Return of God Argument Outline

In this excerpt, Heschel attempts to glean a lesson from the evil in the world. Similar to theologians and the faithful after the Holocaust, Heschel is seeking some justification to still believe in God after tragedy. What Heschel finds is that human nature is inherently opposed to God’s will because of self-interest, requiring an active commitment by humanity to pursue God as the only way to counteract evil in the world. This requires individuals to actively seek ways to improve the world through acts of justice and mercy. His argument is broken down below.

(1) Humanity can only find meaning in God.

Example: Nearly every religion would argue that God holds the ultimate meaning of life, and it is only through knowing God that one can ascertain that meaning.

(2) Individuals have an obligation to pursue meaning in the best way.

Example: Human life must have some purpose; otherwise, there would be no reason for us to exist.

(3) Human self-interest, a component of human nature, is inherently opposed to God’s will.

Example: Suppose Claire is discerning a career. She feels that God is calling her to become a nun, but becoming an investment banker would satisfy her desire for a luxurious life. In this way, God’s will and self-interest are opposed to one another.

(4) Seeking God and His will requires a rejection of self-interest.

Example: In order for Claire to follow God’s will, she must refuse her desire to pursue her self-interest.

(5) The rejection of self-interest necessitates caring for the welfare of others.

Example: Suppose that Claire has decided to become a nun and not an investment banker. By following God’s will and not her self-interest, she now is primarily concerned with caring for others and their wellbeing.

(6) The pursuit of universal redemption, which has the mission of creating a more just world, is the best way to care for others.

Example: A nationwide or global effort to address an injustice will yield greater justice and care than focusing on a single community or individual.

(C) To become closer to God, humanity must commit itself to universal redemption

Connection

The Holocaust and Jewish Identity

The three principles we have discussed form a coherent picture of post-Holocaust theology. After the Holocaust, theologians and the faithful were concerned with explaining why the Holocaust could occur, how to cope with the tragedy, and how to approach a world riddled with such evil. From the principles, we understand that although evil does exist, it is not the fault of God. Rather, it is the result of humanity’s failure to care for one another in the exercise of free will. There is no rational or moral basis for the Holocaust, and a rational approach to the Holocaust would immediately yield a desire to actively prevent such atrocities. From this, one ascertains the mission of pursuing a more just world in which an event like the Holocaust can never happen again.

As you watch this interview with Rabbi Sacks, note that the concept of tikkun olam and the lessons of the Holocaust are not reserved to the Jewish people. Anyone can practice the notion of building a better world by focusing on recognizing and preventing injustice. This is primarily conveyed by demonstrating solidarity with the oppressed and using morality as a guide for actions.

Acknowledgements

This digital essay was prepared by GGL Fellow Blake Ziegler.