Natural Theology: Anselm and Aquinas

Natural theology is a set of philosophical arguments that aim to demonstrate either that a god exists or (assuming he exists) that he possesses certain properties, like being the cause of everything in the universe or being unchanging. Most branches of the major Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — believe that God is importantly transcendent: our typical ways of understanding the physical world are not as reliable when it comes to understanding God. This means that philosophical argumentation is a useful tool in developing theories of god, even if these religions also depend importantly on divine revelation: God sharing information about himself directly in holy texts or in religious experiences.

In this interactive essay we are going to look at arguments from arguably the two greatest natural theologians in the Christian tradition: St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109 AD) and St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274 AD).

Argument

The Ontological Argument

Our first example of natural theology comes from Anselm, who discovered the ontological argument. Anselm’s motto was “faith seeking understanding”. He was a French Benedictine who eventually became the Archibishop of Canterbury. In the Proslogion, Anselm is praying through the philosophical questions he has about God and his nature. In the most famous passage of the Proslogion, Anselm argues that even a “Foole” must concede God exists. “Foole” is his term for atheist… not exactly a charitable way of setting up the argument! But as you’ll see, his argument also suggests some important ideas for how we might understand atheism. We’ll come back to this when we read Nietzsche.

Anselm’s ontological argument proceeds like a geometric proof. He argues that everyone (theist and atheist alike) should agree to some definitions about what God is like. Then he argues from those definition premises for the proposition that God exists. Let’s look at the text, then break it down…

Analyzing the Ontological Argument Part I

Analyzing the Ontological Argument Part I

Truly there is a God, although the fool hath said in his heart, There is no God.

AND so, Lord, do thou, who dost give understanding to faith, give me, so far as thou knowest it to be profitable, to understand that thou art as we believe; and that thou art that which we believe. And indeed, we believe that thou art a being than which nothing greater can be conceived. Or is there no such nature, since the fool hath said in his heart, there is no God? (Psalms xiv. 1). But, at any rate, this very fool, when he hears of this being of which I speak—a being than which nothing greater can be conceived—understands what he hears, and what he understands is in his understanding; although he does not understand it to exist.

For, it is one thing for an object to be in the understanding, and another to understand that the object exists. When a painter first conceives of what he will afterwards perform, he has it in his understanding, but he does not yet understand it to be, because he has not yet performed it. But after he has made the painting, he both has it in his understanding, and he understands that it exists, because he has made it.

Hence, even the fool is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater.

Therefore, if that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, exists in the understanding alone, the very being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, is one, than which a greater can be conceived. But obviously this is impossible. Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.

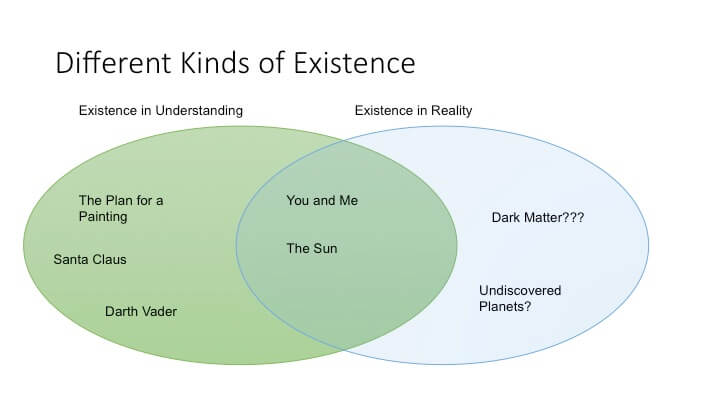

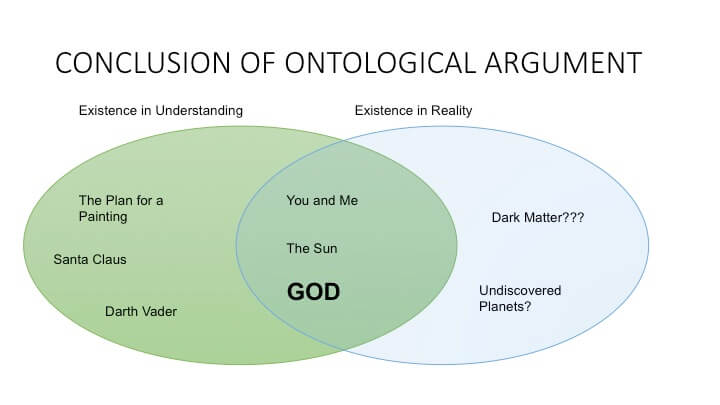

Anselm makes an important distinction between objects that exist in the understanding (i.e. are the kinds of things we can have ideas about) and objects that exist in reality. Some objects (like you and me) exist in both. Some objects are purely imaginary. And some objects exist but are perhaps completely beyond our understanding.

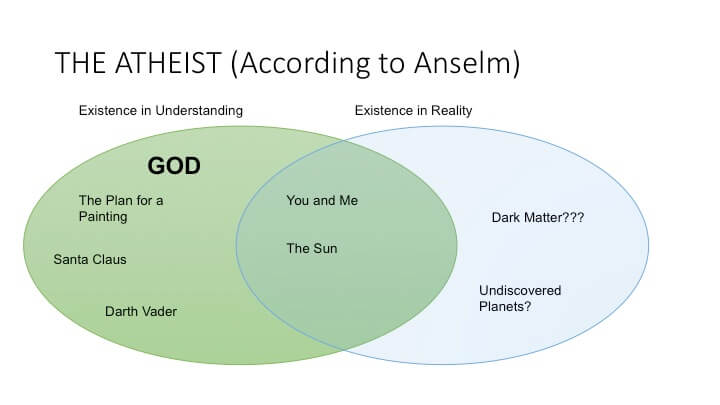

Anselm says the Fool mistakenly classifies God as an object that exists only in the understanding.

But Anselm believes he can demonstrate that God is by definition something in both understand and reality.

Analyzing the Ontological Argument Part II

Analyzing the Ontological Argument Part II

With this distinction, we can now outline Anselm’s argument. There are many formulations of the ontological argument (and how it works is a matter of dispute in the history of philosophy). Here one simple reconstruction.

Premise (1): Everything either exists in the understanding, in reality, or both. [Assumption]

Truly there is a God, although the fool hath said in his heart, There is no God.

AND so, Lord, do thou, who dost give understanding to faith, give me, so far as thou knowest it to be profitable, to understand that thou art as we believe; and that thou art that which we believe. And indeed, we believe that thou art a being than which nothing greater can be conceived. Or is there no such nature, since the fool hath said in his heart, there is no God? (Psalms xiv. 1). But, at any rate, this very fool, when he hears of this being of which I speak—a being than which nothing greater can be conceived—understands what he hears, and what he understands is in his understanding; although he does not understand it to exist.

For, it is one thing for an object to be in the understanding, and another to understand that the object exists. When a painter first conceives of what he will afterwards perform, he has it in his understanding, but he does not yet understand it to be, because he has not yet performed it. But after he has made the painting, he both has it in his understanding, and he understands that it exists, because he has made it.

Hence, even the fool is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater.

Therefore, if that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, exists in the understanding alone, the very being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, is one, than which a greater can be conceived. But obviously this is impossible. Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.

With this distinction, we can now outline Anselm’s argument. There are many formulations of the ontological argument (and how it works is a matter of dispute in the history of philosophy). Here one simple reconstruction.

Premise (1): Everything either exists in the understanding, in reality, or both. [Assumption]

Premise (2): Everyone (theist and atheist) agrees that God is defined as the greatest possible being — the being than which none greater can be conceived.

Truly there is a God, although the fool hath said in his heart, There is no God.

AND so, Lord, do thou, who dost give understanding to faith, give me, so far as thou knowest it to be profitable, to understand that thou art as we believe; and that thou art that which we believe. And indeed, we believe that thou art a being than which nothing greater can be conceived. Or is there no such nature, since the fool hath said in his heart, there is no God? (Psalms xiv. 1). But, at any rate, this very fool, when he hears of this being of which I speak—a being than which nothing greater can be conceived—understands what he hears, and what he understands is in his understanding; although he does not understand it to exist.

For, it is one thing for an object to be in the understanding, and another to understand that the object exists. When a painter first conceives of what he will afterwards perform, he has it in his understanding, but he does not yet understand it to be, because he has not yet performed it. But after he has made the painting, he both has it in his understanding, and he understands that it exists, because he has made it.

Hence, even the fool is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater.

Therefore, if that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, exists in the understanding alone, the very being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, is one, than which a greater can be conceived. But obviously this is impossible. Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.

In Premise (2), Anselm assumes that the atheist will agree that if there were a God, God would be the greatest possible being. Being perfect is one of the divine attributes. Divine attributes play a crucial role in natural theological arguments, because these arguments are typically aimed at showing either something must have this attribute (and that thing=God) or a certain attribute must be understood a particular way. The ontological argument is going to to succeed or fail partly on how we understand what it would be for something to be perfect and the greatest possible thing that can be conceived.

With this distinction, we can now outline Anselm’s argument. There are many formulations of the ontological argument (and how it works is a matter of dispute in the history of philosophy). Here one simple reconstruction.

Premise (1): Everything either exists in the understanding, in reality, or both. [Assumption]

Premise (2): Everyone (theist and atheist) agrees that God is defined as the greatest possible being — the being than which none greater can be conceived.

Premise (3): Existence in reality is greater than existence merely in understanding. [Assumption]

Conclusion: Everyone (theist and atheist) should agree that God also exists in reality.

Truly there is a God, although the fool hath said in his heart, There is no God.

AND so, Lord, do thou, who dost give understanding to faith, give me, so far as thou knowest it to be profitable, to understand that thou art as we believe; and that thou art that which we believe. And indeed, we believe that thou art a being than which nothing greater can be conceived. Or is there no such nature, since the fool hath said in his heart, there is no God? (Psalms xiv. 1). But, at any rate, this very fool, when he hears of this being of which I speak—a being than which nothing greater can be conceived—understands what he hears, and what he understands is in his understanding; although he does not understand it to exist.

For, it is one thing for an object to be in the understanding, and another to understand that the object exists. When a painter first conceives of what he will afterwards perform, he has it in his understanding, but he does not yet understand it to be, because he has not yet performed it. But after he has made the painting, he both has it in his understanding, and he understands that it exists, because he has made it.

Hence, even the fool is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater.

Therefore, if that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, exists in the understanding alone, the very being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, is one, than which a greater can be conceived. But obviously this is impossible. Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.

Objection

The Perfect Island Objection

As soon as Anselm offered his argument it attracted objections. Guanilo, another monk, argued that Anselm’s argument form must not be sound, because if it were, then we could equally prove the existence in reality of some truly crazy entities. Here Guanilo’s “Reply on Behalf of the Fool”. Is he attacking the validity or soundness of Anselm’s argument?

..they say that there is the ocean somewhere an island which, because of the difficulty (or rather the impossibility) of finding that which does not exist, some have called the ‘Lost Island.’ And the story goes that it is blessed with all manner of priceless riches and delights in abundance …and …is superior everywhere in abundance to all those other lands that men inhabit. Now, if anyone tell me that it is like this, I shall easily understand what is said, since nothing is difficult about it. But if he should then go on to say, as though it were a logical consequence of this: You cannot any more doubt that this island that is more excellent than all other lands truly exists somewhere in reality than you can doubt that it is in your mind; and since it is more excellent to exist not only in the mind alone but also in reality, therefore it must needs be that it exists. For if it did not exist, any other land existing in reality would be more excellent than it, and so this island, already conceived by you to be more excellent than others, will not be more excellent. If, I say, someone wishes thus to persuade me that this island really exists beyond all doubt, I should either think that he was joking, or I should find it hard to decide which of us I ought to judge the bigger fool – I, if I agreed with him, or he, if he thought that he had proved the existence of this island..

Guanilo is offering a parody of Anselm’s argument, trying to convince us to reject either Anslem’s logic or the assumptions he makes about greatness as an attribute.

- Premise (1): Everything either exists in the understanding, in reality, or both. [Assumption]

- Premise (2): The Magic Island is defined as the perfect island — the island than which none greater can be conceived. [Parody Premise]

- Premise (3): Existence in reality is greater than existence merely in understanding. [Assumption]

- Conclusion: Everyone should agree that the Magic Island also exists in reality.

The parody gives us some reason to question Anselm’s logic. But where does the ontological argument for God’s existence go wrong? Should we think that existence does not making something “greater”?

Argument

The Five Ways (Arguments) of Aquinas

St. Thomas Aquinas took a different approach for arguing for God’s existence. He focuses on the need for there to be some entity responsible for all of the change we observe in the world — an “unmoved mover” at the foundation of everything in reality. That entity, he argues, must be God. This approach tends to be called the cosmological argument(s) for the existence of God. We will be reading more Aquinas in this class, and like Anselm, he has a distinctive way of presenting his arguments. Here is an introduction to reading Aquinas from ND President John Jenkins (also an Aquinas scholar). Here you can download a PDF of the text of the Five Ways, in Aquinas’s Summa Theologica.

(Developer note: Video that was embedded here was made private by its Owner.)

Way 1: The Argument from Change

Way 1: The Argument from Change

Note: Motion or “motus” here means movement or change. Not just physical movement.

It is certain, and evident to our senses, that in the world some things are in motion. Now whatever is in motion is put in motion by another, for nothing can be in motion except it is in potentiality to that towards which it is in motion; whereas a thing moves inasmuch as it is in act. For motion is nothing else than the reduction of something from potentiality to actuality. But nothing can be reduced from potentiality to actuality, except by something in a state of actuality.

Thus that which is actually hot, as fire, makes wood, which is potentially hot, to be actually hot, and thereby moves and changes it.

Now it is not possible that the same thing should be at once in actuality and potentiality in the same respect, but only in different respects. For what is actually hot cannot simultaneously be potentially hot; but it is simultaneously potentially cold. It is therefore impossible that in the same respect and in the same way a thing should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Therefore, whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put in motion by the first mover; as the staff moves only because it is put in motion by the hand. Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.

Key Concept: Motion is a change from potentiality to actuality.

(1) In the world some things are in motion.

(2) Whatever is in motion is put in motion by another.

(3) Nothing can be changed from potentiality to actuality, except by something in a state of actuality.

(4) And it is not possible that the same thing should be at once in actuality and potentiality in the same respect, but only in different respects.

Conclusion 1: Therefore, it is impossible that in the same respect and in the same way a thing should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself.

(5) Whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another.

(6) If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again.

(7) But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover).

Conclusion 2: Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other, and this everyone understands to be God.

Way 2: The Argument from Causation

Way 2: The Argument from Causation

Note: Think of causation here in a broad sense. It refers to any causes that bring about effects in the world. For example, parents are the joint cause of their children. The cause of a sculpture is the artist who created it.

The second way is from the nature of the efficient cause. In the world of sense we find there is an order of efficient causes.

There is no case known (neither is it, indeed, possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible. Now in efficient causes it is not possible to go on to infinity, because in all efficient causes following in order, the first is the cause of the intermediate cause, and the intermediate is the cause of the ultimate cause, whether the intermediate cause be several, or only one. Now to take away the cause is to take away the effect. Therefore, if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate cause. But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly false. Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name of God.

(1) Nothing is the efficient cause of itself (for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible).

(2) To take away the cause is to take away the effect.

Conclusion 1: Therefore, if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate cause.

(3) But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly false.

(4) Thus, in efficient causes it is not possible to go on to infinity.

Conclusion 2: Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name of God.

Way 3: The Argument from Contingency

Way 3: The Argument from Contingency

We find in nature things that are possible to be and not to be, since they are found to be generated, and to corrupt, and consequently, they are possible to be and not to be. But it is impossible for these always to exist, for that which is possible not to be at some time is not. Therefore, if everything is possible not to be, then at one time there could have been nothing in existence. Now if this were true, even now there would be nothing in existence, because that which does not exist only begins to exist by something already existing. Therefore, if at one time nothing was in existence, it would have been impossible for anything to have begun to exist; and thus even now nothing would be in existence — which is absurd. Therefore, not all beings are merely possible, but there must exist something the existence of which is necessary. But every necessary thing either has its necessity caused by another, or not. Now it is impossible to go on to infinity in necessary things which have their necessity caused by another, as has been already proved in regard to efficient causes. Therefore we cannot but postulate the existence of some being having of itself its own necessity, and not receiving it from another, but rather causing in others their necessity. This all men speak of as God.

(1) Since objects in the universe come into being and pass away, it is possible for those objects to exist or for those objects not to exist at any given time.

(2) Since objects are countable, the objects in the universe are finite in number.

(3) If, for all existent objects, they do not exist at some time, then, given infinite time, there would be nothing in existence. (Nothing can come from nothing—there is no creation ex nihilo) for individual existent objects.

(4) But, in fact, many objects exist in the universe.

Conclusion: a Necessary Being (i.e., a Being of which it is impossible that it should not exist) exists.

By this third way, Aquinas has focused his attention on two important divine attributes that are important to his argument.

- • He assumes God is the first cause or unmoved mover of everything else. Put another way, for Aquinas’s argument to work we must at least agree that whatever the self-sustained original creator is, that is God.

- • He assumes that God is also a necessary being. Seemingly everything else in the universe that exists could have not existed. We might not have been born and someday we will die. The Eiffel Tower, Mt. Everest, the Milky Way — all had times when they came into existence and if conditions were different might have never existed. God, on the other hand, has no start or end and couldn’t fail to exist on Aquinas’s definition.

Way 4: The Argument from Degree

Way 4: The Argument from Degree

The fourth way is taken from the gradation to be found in things. Among beings there are some more and some less good, true, noble and the like. But “more” and “less” are predicated of different things, according as they resemble in their different ways something which is the maximum, as a thing is said to be hotter according as it more nearly resembles that which is hottest; so that there is something which is truest, something best, something noblest and, consequently, something which is uttermost being; for those things that are greatest in truth are greatest in being, as it is written in Metaph. ii. Now the maximum in any genus is the cause of all in that genus; as fire, which is the maximum heat, is the cause of all hot things. Therefore there must also be something which is to all beings the cause of their being, goodness, and every other perfection; and this we call God.

Note: In this argument Aquinas seems to assume that is some property can be spoken of as coming in greater and lesser degrees, then there must be some being that has that property to the maximal degree. For instance, there could be more of less cold, therefore there is a maximally cold being. Many philosophers have challenged this assumption.

(1) All things are more or less perfect, more or less beautiful, etc

(2) But gradation of each perfections implies the existence of a being with the maximal degree of that perfection.

(3) And we know that that which is greatest in truth is also greatest in wisdom, beauty, and all the other perfections.

Conclusion: There exists a maximally perfect being, whom we call God.

*Compare Aquinas’s (2) to Premise (2) of Anselm’s Ontological Argument. How is it different?

Way 5: The Argument from Design

Way 5: The Argument from Design

The fifth way is taken from the governance of the world. We see that things which lack intelligence, such as natural bodies, act for an end, and this is evident from their acting always, or nearly always, in the same way, so as to obtain the best result. Hence it is plain that not fortuitously, but designedly, do they achieve their end. Now whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence; as the arrow is shot to its mark by the archer. Therefore some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end; and this being we call God.

Here we see the profound influence of Aristotle on Aquinas. Recall the assumptions in the function argument in Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics. Aquinas argues…

(1) All things act toward some end or purpose

(2) But only things that are designed act toward ends or purposes

(3) Therefore all things are designed

(4) But anything that’s designed has a designer

Conclusion: A designer of all things exists, and this we call God

Objection

Some Objections to the Five Ways

Aquinas considers and replies to objections to his argument at the end of the Five Ways.

Objection 1: A Version of the Problem of Evil

It seems that God does not exist; because if one of two contraries be infinite, the other would be altogether destroyed. But the word “God” means that He is infinite goodness. If, therefore, God existed, there would be no evil discoverable; but there is evil in the world. Therefore God does not exist.

Aquinas’s Reply: As Augustine says (Enchiridion xi): “Since God is the highest good, He would not allow any evil to exist in His works, unless His omnipotence and goodness were such as to bring good even out of evil.” This is part of the infinite goodness of God, that He should allow evil to exist, and out of it produce good.

Objection 2: What if there are multiple explanations and none of them require God?

Further, it is superfluous to suppose that what can be accounted for by a few principles has been produced by many. But it seems that everything we see in the world can be accounted for by other principles, supposing God did not exist. For all natural things can be reduced to one principle which is nature; and all voluntary things can be reduced to one principle which is human reason, or will. Therefore there is no need to suppose God’s existence.

Aquinas’s Reply: Since nature works for a determinate end under the direction of a higher agent, whatever is done by nature must needs be traced back to God, as to its first cause. So also whatever is done voluntarily must also be traced back to some higher cause other than human reason or will, since these can change or fail; for all things that are changeable and capable of defect must be traced back to an immovable and self necessary first principle, as was shown in the body of the Article.

Other objections Aquinas does not consider in this passage. For instance we might wonder…

Objection 3: What if there just is an infinite chain of causes and explanations that never stops?

Objection 4: And how can the design argument explain all of the apparent design failures in the world?

Summary and Next Steps

As we’ve seen, the natural theological arguments tend to reply on premises about key divine attributes. Atheists can resist the arguments by denying that these attributes are coherent or possible (i.e. it is incoherent to imagine a perfect being). Or they can resist the logic of the arguments. A further question is whether theism could be rational even if there is no decisive argument proving God’s existence or nature. This introduces the broader debate in philosophy of religion — what does rational faith require of us?

Acknowledgments

This digital essay was prepared by Paul Blaschko and Meghan Sullivan.