Meditations: Marcus Aurelius

Introduction

Marcus Aurelius

-

Themes of the Meditations

-

The Common Good & Living in the Moment

The themes of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations we should focus on are:

- • Death and the shortness of life

- • Importance of rationality and will

- • Accepting others’ shortcomings

- • Avoiding desire for fame and pleasure

- • Accepting course of nature and living by its forces

The following passages are from Book VII of the Meditations. The full text of Meditations Book VII can be found using this link and skipping to page 129.

Book VII of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations contains a series of observations on the nature of change and the forces of life itself. The work was not intended for an audience, but rather as a collection of meditative notes-to-self.

One remarkable topic on which Marcus Aurelius writes is personal ability as it may apply to the common good:

Is my intellect sufficient for this business or not? If it is, I will make use of my talent as given me by heaven for that purpose. If not, I will either let it alone, and resign it to a better capacity, unless that be contrary to my duty, or else I will do what I can. I will give my advice, and put the executing part into an abler hand, and thus the right moment and the general interest may be secured. For whatsoever I act, either by myself, or in conjunction with another, I am always to aim at the advantage of the community.

He continues to say our actions should not be motivated by the want for fame or recognition.

How many famous men are dropped out of history and forgotten? And how many, that promised to keep up other people’s names, have lost their own?

And we ought to be open to the helpful abilities of our peers:

Never be ashamed of assistance. Like a soldier at the storming of a town, your business is to maintain your post, and execute your orders. Now suppose you happen to be lame at an assault, and cannot mount the breach upon your own feet, will you not suffer your comrade to help you?

On the course of life itself, Marcus Aurelius reminds himself of the importance of living in the moment, but not clinging to any moment which has passed.

Be not disturbed about the future, for if ever you come to it, you will have the same reason for your guide, which preserves you at present.

Key Principle

Rationality

The importance of rationality and will is a central tenet of the Meditations.

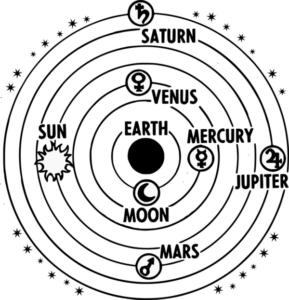

- All parts of the universe are interwoven and tied together with a sacred bond. And no one thing is foreign or unrelated to another. This general connection gives unity and ornament to the world. For the world, take it altogether, is but one. There is but one sort of matter to make it of; one God that pervades it; and one law to guide it, the common reason of all rational beings; and one truth; if, indeed, beings of the same kind, and endued with the same reason, have one and the same perfection.

- Everything material quickly disappears into the universal matter. And everything causal is quickly absorbed into the universal reason. And the memory of everything is quickly overwhelmed by time.

- With rational beings action in accordance with nature and reason is the same thing.

It is our responsibility, then, to act in line with reason.

- Either stand upright upon your own legs, or upon your crutches.

For Marcus, accidents — and all sorts of things we have no control over — will happen in a lifetime, but it’s vital to realize that one’s response to these thing can influence things for better or worse. Stoics like Marcus encourage us to resist overreacting or making things worse. So long as we remain solid in our understanding of the universe, and so long as we remember that external change does not cut at what really matters in life, we can refuse to allow things out of our control to have an outsized impact on our lives. The same principle applies to interpersonal problems.

- Let accidents happen to such as are liable to the impression, and those that feel misfortune may complain of it, if they please. As for me, let what will come, I can receive no damage by it, unless I think it a calamity; and it is in my power to think it none, if I have a mind to it.

- Let people’s tongues and actions be what they will, my business is to be good. And make the same speech to myself, that a piece of gold, or an emerald, or purple should. Let people talk and act as they please; I must be an emerald, and I must keep my color.

Properly responding to things outside of our control depends on being able to maintain a positive mindset. Marcus Aurelius marvels at the capacity of the mind with the remark:

- Does the mind ever cause herself disturbance? Does she bring fears and passions upon herself? Let any other body try to frighten or trouble her if they can, for of her own conviction she will not turn to such impressions. And as for this small carcass, let it take care not to feel, and if it does, say so. But the soul, the seat of passion and pain, which forms an opinion on these things, need suffer nothing, unless she throws herself into these fancies and fears. For the mind is in her own nature self-sufficient, and must create her wants before she can feel them. This privilege makes her undisturbed and above restraint, unless she teazes and puts fetters upon herself.

Key Principle

What is Stoic Meditation?

What is Stoic Meditation

-

Meditation?

-

A Brief Overview of Meditative Exercises

-

Comparing Different Types of Meditation

The title of Marcus’s text “The Meditations” might cause you to wonder: what do stoics meditate about? And why is meditation such an important practice for stoic philosophers? As you’ve seen, stoics value rationality — especially in the face of change or unpredictability. The stoic ideal is someone who is able to maintain calm, cool, and collected, even as things around them are chaotic and uncertain.

To attain this ideal, stoics recommend meditating on images or ideas that will counteract our immediate (often negative) emotional reactions to things. Worried about your reputation being destroyed? Remember that “It will not be long before you will have forgotten all the world, and in a little time all the world will forget you too.” Worried that one of your projects is going to fail? “That being which governs nature will quickly change the present face of it. One thing will be made out of another by frequent revolutions. And thus the world will be always new.” Marcus even recommends calling to mind particular images or thoughts that remind you that all that matters in life is virtue.

Stoic meditation exercises have much in common with other forms of meditation. Like “mindfulness” meditation, they encourage us to take a step back from our immediate perceptions and judgments to achieve a calm (and for the stoic, rational) mental state. Like meditation encouraged in the course of “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy,” stoicism thinks that this clarity can help us avoid emotional distortions or biases.

Still, there are important differences.

First, stoic meditation comes with its own presuppositions about what the world is like, and where value comes from. An underlying unity in nature, overseen by an impersonal, god-like figure is something stoics rely on in encouraging their followers to “detach” themselves from life’s big changes and transitions.

Another thing that’s very important to the stoics is that the point of meditation is to realize that virtue is the only thing that matters in life. In this way, they encourage us to using meditation to detaching from everything else. This includes things like money or material goods, but also our natural love and care for other people. For the stoic, undue attachment to others will cause inner-strife and is, itself, something that can distort our thinking.

Connection

Suffering

Suffering and death are some of the biggest topics of Marcus’s “Meditations,” because it is a state of flux that’s always threatening to distract us from what really matters. Here are some of his meditations on these topics.

- Concerning death: It is a dispersion if there are atoms; but if the universe is a unity, it is either extinction or change.

- As for pain, if it is intolerable it will quickly dispatch you. If it stays long it is bearable. Your mind in the meantime preserves herself calm by the strength of the opining faculty, and suffers nothing. And for your limbs that are hurt by the pain, if they can complain, let them do it.

- A saying of Plato, “He that has raised his mind to a due pitch of greatness, that has carried his view through the whole extent of matter and time, do you imagine such an one will think much of human life? Not at all (says the other man in the dialogue). What then? Will the fear of death afflict him? Far from it.”

- “You are mightily out if you think a man that is good for anything is either afraid of living or dying. No; his concern is only whether in doing anything he is doing right or wrong–acting the part of a good man or bad.”

To see more about how a modern stoic might think about suffering, watch this short video.

Stoicism and the Good Life

Stoicism and the Good Life

-

Marcus’s Philosophy of the Good Life

-

Breaking It Down

Here’s a passage in which Marcus reflects explicitly on what we might call his “Philosophy of the Good Life:”

It is always and everywhere in your power to resign to the gods, to be just to mankind, and to examine every impression with such care that nothing may enter that is not well examined. Never make any rambling enquiries after other people’s thoughts, but look directly at the mark which nature has set you. Nature, I say, either that of the universe or your own; the first leads you to submission to Providence, the latter to act as becomes you. Now that which is suitable to the frame and constitution of things is what becomes them. To be more particular, the rest of the world is designed for the service of rational beings in consequence of this general appointment, by which the lower order of things are made for the use of the more noble. And rational creatures are designed for the advantage of each other. Now a social temper is that which human nature was principally intended for; the next thing designed in our being is to be proof against corporeal impressions, it being the peculiar privilege of reason to move within herself, and not suffer sensation or passion to break in upon her; for these are both of animal and inferior quality. But the understanding part claims a right to govern, and will not bend to matter or appetite; and good reason for it, since she was born to command and make use of them. The third main requisite in a rational being is to secure the assent from rashness and mistake. Let your mind but compass these points, and stick to them, and then she is mistress of everything which belongs to her.

Marcus’s view of the good life can be broken down into the following principles:

- Resign to the gods: understand that life is outside of your control and accept that nature will predominate.

- Be just to mankind: humans are designed to serve one another rather in contrast to how “the lower order of things” is designed to be used for the good of rational beings.

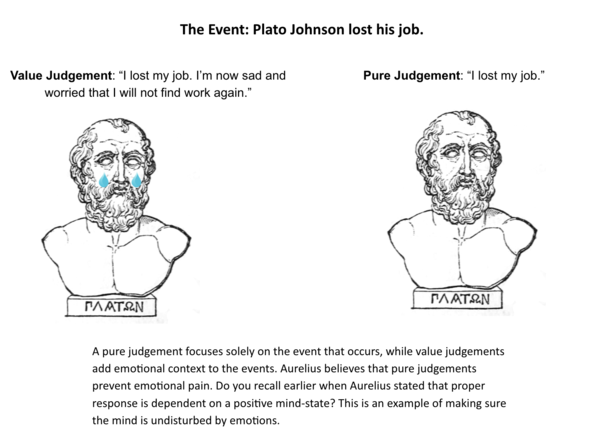

- Examine every impression with such care that nothing may enter that is not well examined: make pure judgments that are not clouded with value or emotional judgments.

See below for an illustration of how this might play out in a particular case.

Key Principle

Fate

Resignation to “fate” (sometimes thought of as “the will of the gods” in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy) is also a key part of stoicism, and a theme that runs throughout Marcus’s meditations:

- We ought to spend the remainder of our life according to nature, as if we were already dead, and had come to the end of our term.

- Let your fate be your only inclination, for there is nothing more reasonable.

- Look inwards, for you have a lasting fountain of happiness at home that will always bubble up if you will but dig for it.

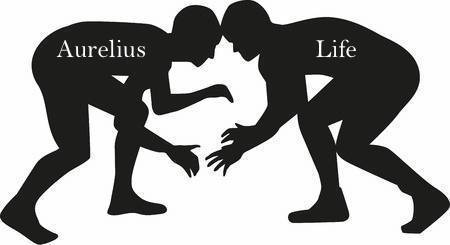

- The art of living resembles wrestling more than dancing, for here a man does not know his movement and his measures beforehand.

- It is a saying of Plato’s, that no soul misses truth of her own good-will. The same may be said with reference to justice, sobriety, good nature, and the like. Be particularly careful to remember this, for it will help to sweeten your temper towards all men.

Aurelius states that life is more like wrestling than dancing. Dancing suggests that there is rhythm, planned movements, and overall order and control. Wrestling, on the contrary, is a more appropriate comparison since we never know what our next move entails and is often dictated by the circumstances life throws at us.

Connection

Temper

In closing, we’ll leave you with some thoughts Marcus has about controlling life’s more difficult emotions. In the “Meditations,” he shifts from a general discussion of fate to a reflection on temper and the virtuous treatment of others. Marcus Aurelius reflects:

- Do not return the temper of ill-natured people upon themselves, nor treat them as they do the rest of mankind.

- Nature has not wrought your composition so close that you cannot withdraw within your own limits, and do your own business yourself; for a man may be first-rate in virtue and true value, and yet be very obscure at the same time. You may likewise observe that happiness has very few wants. Granting your talent will not reach very far into logic, this cannot hinder the freedom of your mind, nor deprive you of the blessings of sobriety, beneficence, and resignation.

- He that is come to the top of wisdom and practice, spends every day as if it were his last, and is never guilty of over-excitement, sluggishness, or insincerity.

- It is great folly not to part with your own faults which is possible, but to try instead to escape from other people’s faults, which is impossible.

- Whatever business tends neither to the improvement of your reason, nor the benefit of society, the rational and social faculty thinks beneath it.

- Nobody is ever tired of advantages. Now to act in conformity to the laws of nature is certainly an advantage. Do not you therefore grow weary of doing good offices, whereby you receive the advantages.

To tie these threads together, here’s a video introduction to stocism (though not Marcus’s version of it in particular) that helps provide a broader perspective.

Acknowledgments

This digital essay was prepared by GGL Fellows Devin Diggs and Elle Dietz in collaboration with the GGL Teaching Team.