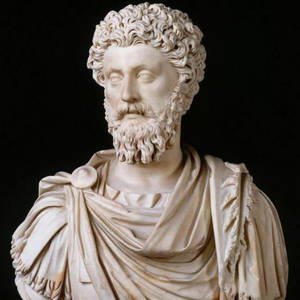

Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations

Introduction

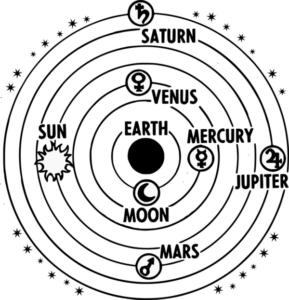

Meditations was written by Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius in the years 161-180 when he was planning military campaigns, though he never titled it or intended for it to be published. It was meant to record his own private notes and ideas on Stoicism Philosophy. It was written in the form of twelve books, widely discussing the importance of analyzing one’s judgment of self and others and developing a cosmic perspective. In these two sections, he goes into the most important virtues as well as things to keep in mind for living the good life. You can read a PDF of the text here if you prefer to work through that. Note, though, that this is the full text while the digital essay only covers specific excerpts.

Video

See this video for a further explanation of Stoicism and Meditations.

Key Terms

- Stoicism

- The Virtues

- Integrity

- Humility

- Generosity

Book 1: DEBTS AND LESSONS

In this section, Marcus Aurelius expresses gratitude for certain figures in his life as well as the virtues that they possessed. Note which virtues that he especially admires and think about how they may apply to the way that someone may choose their career.

1. MY GRANDFATHER VERUS

Character and self control.

2. MY FATHER (FROM MY OWN MEMORIES AND HIS REPUTATION)

Integrity and manliness.

3. MY MOTHER

Her reverence for the divine, her generosity, her inability not only to do wrong but even to conceive of doing it. And the simple way she lived—not in the least like the rich.

4. MY GREAT-GRANDFATHER

To avoid the public schools, to hire good private teachers, and to accept the resulting costs as money well-spent.

5. MY FIRST TEACHER

Not to support this side or that in chariot-racing, this fighter or that in the games. To put up with discomfort and not make demands. To do my own work, mind my own business, and have no time for slanderers.

6. DIOGNETUS

7. RUSTICUS Not to waste time on nonsense. Not to be taken in by conjurors and hoodoo artists with their talk about incantations and exorcism and all the rest of it. Not to be obsessed with quail-fighting or other crazes like that. To hear unwelcome truths. To practice philosophy, and to study with Baccheius, and then with Tandasis and Marcianus. To write dialogues as a student. To choose the Greek lifestyle— the camp-bed and the cloak.

The recognition that I needed to train and discipline my character.

Not to be sidetracked by my interest in rhetoric. Not to write treatises on abstract questions, or deliver moralizing little sermons, or compose imaginary descriptions of The Simple Life or The Man Who Lives Only for Others. To steer clear of oratory, poetry and belles lettres.

Not to dress up just to stroll around the house, or things like that. To write straightforward letters (like the one he sent my mother from Sinuessa). And to behave in a conciliatory way when people who have angered or annoyed us want to make up.

To read attentively—not to be satisfied with “just getting the gist of it.” And not to fall for every smooth talker. And for introducing me to Epictetus’s lectures—and loaning me his own copy.

8. APOLLONIUS

Independence and unvarying reliability, and to pay attention to nothing, no matter how fleetingly, except the logos. And to be the same in all circumstances—intense pain, the loss of a child, chronic illness. And to see clearly, from his example, that a man can show both strength and flexibility.

His patience in teaching. And to have seen someone who clearly viewed his expertise and ability as a teacher as the humblest of virtues.

And to have learned how to accept favors from friends without losing your self-respect or appearing ungrateful.

9. SEXTUS

Kindness.

An example of fatherly authority in the home. What it means to live as nature requires.

Gravity without airs.

To show intuitive sympathy for friends, tolerance to amateurs and sloppy thinkers. His ability to get along with everyone: sharing his company was the highest of compliments, and the opportunity an honor for those around him.

To investigate and analyze, with understanding and logic, the principles we ought to live by.

Not to display anger or other emotions. To be free of passion and yet full of love.

To praise without bombast; to display expertise without pretension.

10. THE LITERARY CRITIC ALEXANDER

Not to be constantly correcting people, and in particular not to jump on them whenever they make an error of usage or a grammatical mistake or mispronounce something, but just answer their question or add another example, or debate the issue itself (not their phrasing), or make some other contribution to the discussion—and insert the right expression, unobtrusively.

11. FRONTO

To recognize the malice, cunning, and hypocrisy that power produces, and the peculiar ruthlessness often shown by people from “good families.”

12. ALEXANDER THE PLATONIST

13. CATULUS

Not to shrug off a friend’s resentment—even unjustified resentment—but try to put things right.

To show your teachers ungrudging respect (the Domitius and Athenodotus story), and your children unfeigned love.

14. [MY BROTHER] SEVERUS

To love my family, truth and justice. It was through him that I encountered Thrasea, Helvidius, Cato, Dion and Brutus, and conceived of a society of equal laws, governed by equality of status and of speech, and of rulers who respect the liberty of their subjects above all else.

And from him as well, to be steady and consistent in valuing philosophy.

And to help others and be eager to share, not to be a pessimist, and never to doubt your friends’ affection for you. And that when people incurred his disapproval, they always knew it. And that his friends never had to speculate about his attitude to anything: it was always clear.

15. MAXIMUS

Self-control and resistance to distractions.

Optimism in adversity—especially illness.

A personality in balance: dignity and grace together. Doing your job without whining.

Other people’s certainty that what he said was what he thought, and what he did was done without malice. Never taken aback or apprehensive. Neither rash nor hesitant—or bewildered, or at a loss. Not obsequious—but not aggressive or paranoid either.

The sense he gave of staying on the path rather than being kept on it.

That no one could ever have felt patronized by him—or in a position to patronize him.

A sense of humor.

16. MY ADOPTED FATHER

Compassion. Unwavering adherence to decisions, once he’d reached them. Indifference to superficial honors. Hard work. Persistence.

Listening to anyone who could contribute to the public good.

His dogged determination to treat people as they deserved.

A sense of when to push and when to back off. Putting a stop to the pursuit of boys.

His altruism. Not expecting his friends to keep him entertained at dinner or to travel with him (unless they wanted to). And anyone who had to stay behind to take care of something always found him the same when he returned.

His searching questions at meetings. A kind of single mindedness, almost, never content with first impressions, or breaking off the discussion prematurely.

His constancy to friends—never getting fed up with them, or playing favorites.

Self-reliance, always. And cheerfulness.

And his advance planning (well in advance) and his discreet attention to even minor things.

His restrictions on acclamations—and all attempts to flatter him.

His constant devotion to the empire’s needs. His stewardship of the treasury. His willingness to take responsibility—and blame—for both.

His attitude to the gods: no superstitiousness. And his attitude to men: no demagoguery, no currying favor, no pandering. Always sober, always steady, and never vulgar or a prey to fads.

The way he handled the material comforts that fortune had supplied him in such abundance—without arrogance and without apology. If they were there, he took advantage of them. If not, he didn’t miss them.

No one ever called him glib, or shameless, or pedantic. They saw him for what he was: a man tested by life, accomplished, unswayed by flattery, qualified to govern both himself and them.

His respect for people who practiced philosophy—at least, those who were sincere about it. But without denigrating the others—or listening to them.

His ability to feel at ease with people—and put them at their ease, without being pushy.

His willingness to take adequate care of himself. Not a hypochondriac or obsessed with his appearance, but not ignoring things either. With the result that he hardly ever needed medical attention, or drugs or any sort of salve or ointment.

This, in particular: his willingness to yield the floor to experts—in oratory, law, psychology, whatever—and to support them energetically, so that each of them could fulfill his potential.

That he respected tradition without needing to constantly congratulate himself for Safeguarding Our Traditional Values.

Not prone to go off on tangents, or pulled in all directions, but sticking with the same old places and the same old things.

The way he could have one of his migraines and then go right back to what he was doing—fresh and at the top of his game.

That he had so few secrets—only state secrets, in fact, and not all that many of those.

The way he kept public actions within reasonable bounds —games, building projects, distributions of money and so on —because he looked to what needed doing and not the credit to be gained from doing it.

No bathing at strange hours, no self-indulgent building projects, no concern for food, or the cut and color of his clothes, or having attractive slaves. (The robe from his farm at Lorium, most of the things at Lanuvium, the way he accepted the customs agent’s apology at Tusculum, etc.)

He never exhibited rudeness, lost control of himself, or turned violent. No one ever saw him sweat. Everything was to be approached logically and with due consideration, in a calm and orderly fashion but decisively, and with no loose ends.

You could have said of him (as they say of Socrates) that he knew how to enjoy and abstain from things that most people find it hard to abstain from and all too easy to enjoy. Strength, perseverance, self-control in both areas: the mark of a soul in readiness—indomitable.

(Maximus’s illness.)

17. THE GODS

That I had good grandparents, a good mother and father, a good sister, good teachers, good servants, relatives, friends—almost without exception. And that I never lost control of myself with any of them, although I had it in me to do that, and I might have, easily. But thanks to the gods, I was never put in that position, and so escaped the test.

That I wasn’t raised by my grandfather’s girlfriend for longer than I was. That I didn’t lose my virginity too early, and didn’t enter adulthood until it was time—put it off, even.

That I had someone—as a ruler and as a father—who could keep me from being arrogant and make me realize that even at court you can live without a troop of bodyguards, and gorgeous clothes, lamps, sculpture—the whole charade. That you can behave almost like an ordinary person without seeming slovenly or careless as a ruler or when carrying out official obligations.

That I had the kind of brother I did. One whose character challenged me to improve my own. One whose love and affection enriched my life.

That my children weren’t born stupid or physically deformed.

That I wasn’t more talented in rhetoric or poetry, or other areas. If I’d felt that I was making better progress I might never have given them up.

That I conferred on the people who brought me up the honors they seemed to want early on, instead of putting them off (since they were still young) with the hope that I’d do it later.

That I knew Apollonius, and Rusticus, and Maximus. That I was shown clearly and often what it would be like to live as nature requires. The gods did all they could— through their gifts, their help, their inspiration—to ensure that I could live as nature demands. And if I’ve failed, it’s no one’s fault but mine. Because I didn’t pay attention to what they told me—to what they taught me, practically, step by step.

That my body has held out, especially considering the life I’ve led.

That I never laid a finger on Benedicta or on Theodotus. And that even later, when I was overcome by passion, I recovered from it.

That even though I was often upset with Rusticus I never did anything I would have regretted later.

That even though she died young, at least my mother spent her last years with me.

That whenever I felt like helping someone who was short of money, or otherwise in need, I never had to be told that I had no resources to do it with. And that I was never put in that position myself—of having to take something from someone else.

That I have the wife I do: obedient, loving, humble. That my children had competent teachers.

Remedies granted through dreams—when I was coughing blood, for instance, and having fits of dizziness. And the one at Caieta.

That when I became interested in philosophy I didn’t fall into the hands of charlatans, and didn’t get bogged down in writing treatises, or become absorbed by logic-chopping, or preoccupied with physics.

All things for which “we need the help of fortune and the gods.”