Janna Thompson’s “Identity and Obligation in a Transgenerational Polity”: Think Beyond the Grave

Introduction

Janna Thompson is a professor of Philosophy at La Trobe University in Australia. Her work focuses on political and moral philosophy, and she is especially known for her ideas about intergenerational justice as well as her extensive writing on environmental and feminist philosophy. She often contributes opinion pieces to magazines about hot topics in ethics, from her take on the technology that will make humans live longer to what to do with recovered Nazi art. You can read a PDF of the full text here if you want to dive deeper into the topic of this digital essay.

Key Concepts

- Political Liberalism

- Political Communitarianism

- Duties to Other Generations

- Lifetime-Transcending Interests

What Does an Intergenerational Society Look Like?

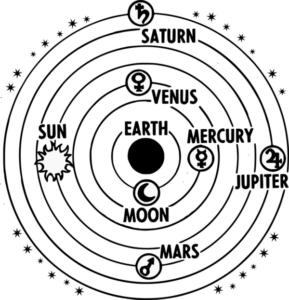

In this introductory section, Thompson pits two theories against each other, Liberalism and Communitarianism, in order to describe intergenerational societies.

What Does an Intergenerational Society Look Like?

-

Political Liberalism

-

Political Communitarianism

Liberalism dates back to the Enlightenment when John Lock put forth his ideas about a social contract or an agreement between the government and its citizens that would maximize individual liberty. Liberalist movements tend to push back against hereditary privilege and absolute monarchy, and instead promoted individual rights, secularism, and a market economy. Later waves of Liberalism focused on civil rights, as well as gender and racial equality.

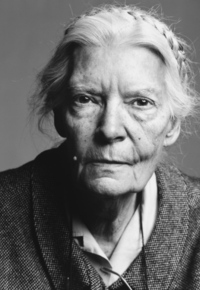

Contrary to Liberalism, Communitarianism places emphasis on community relationships. Political Communitarianism began in the 19th century, but it is not necessarily linked to Communism, despite the similarity in name. The main thesis of this way of thinking is this: the community shapes the individual and that the social realm is of the utmost importance. The Catholic Worker movement, started by Dorothy Day, implemented a communitarian philosophy by providing communities to those who might not have one through their various hospitality houses.

A political society is intergenerational. Citizens are born into a pre‐existing polity that in most cases will continue to exist, perhaps for many generations, after they are dead…. They understand themselves and their political actions in a historical framework that connects the deeds of past generations to their own deeds and to aspirations for the future of their society. They see themselves as carrying on a tradition, maintaining a valued institution, righting a historical wrong, or continuing a struggle to achieve a national ideal. They honour their nation’s dead, or the dead of other communities to which they belong, and make sacrifices for posterity. They preserve their heritage and pass it on to future generations. Their government makes agreements and incurs obligations which succeeding generations are supposed to honour. Intergenerational relationships, and the obligations and entitlements that go with them, are central to the moral fabric of a political society. A nation for them is, in essence, a transgenerational polity: a society in which the generations are bound together in relationships of obligation and entitlement.1

Theories of justice, right and political responsibility ought to reflect the importance to citizens, and to the nature and operation of their society, of transgenerational relationships. Liberal theories generally fail to do this.

…

The first aspect of this problem is that liberal theories, classical and modern, focus on relations between contemporaries. Intergenerational relationships are treated as marginal concerns: as a problematic addendum to theories that focus on contemporaries. The second aspect of the problem has to do with the conception of the individual on which liberal theories of justice and right depend. Liberals tend to take as central the lifetime interests of individuals: the goals, needs, and motivations that relate either to their present wants and circumstances or to their ideas about what they want to achieve or enjoy during the course of their lives. However, the scope of individual interest is not confined to concerns of a lifetime. Individuals have ideas about the good, which are bound up with their hopes for their descendants and their regard for their forebears. They have views about how people should treat and regard them after their death. They have projects and things of value that they want to pass on to successors. They care about their heritage and what happens to it. They take pride in or feel shame concerning events of their nation’s history. They want their ideals to flourish in future generations. Liberals do not deny that individuals often have such interests, but they tend to treat them as peripheral, or even as suspect to the extent that they threaten to get in the way of present and future individuals living their lives free from the impositions of the past. A theory of the transgenerational polity, I will argue below, ought to regard these interests as central to the lives of individuals and to an account of relationships between the generations.

In searching for a more adequate approach to justice, obligation, and responsibility in a transgenerational polity, it seems appropriate to turn to those theories that are labeled ‘communitarian’.

…

There are two ways in which communitarians typically distinguish themselves from liberals. The first is that they insist that the self is essentially embedded in a community…

I am someone’s son or daughter, someone else’s cousin or uncle . . . I belong to this clan, that tribe, this nation. Hence what is good for me has to be the good for one who inhabits these roles. As such I inherit from the past of my family, my city, my tribe, my nation, a variety of debts, inheritances, rightful expectations and obligations. These constitute the given of my life, my moral starting point.

The second idea typically advanced by communitarians is that members of a community share a common good, and that it is this good, above all, that defines their relationships and obligations. Communitarians are able to give relationships between generations a central place in their view of community, and thus are well placed to provide a more satisfactory understanding of obligations in a transgenerational polity. For them obligations arise out of relationships of cooperation in a community based on a common idea of the good, and are thus truly transgenerational.

Main Idea

Thompson examines the flaws in Liberalism and the benefits of Communitarianism to suggest that Communitarianism more effectively describes intergenerational societies. Thompson thinks Communitarianism is better (though not perfect), because it places greater importance on how the individual is embedded in a particular community and the obligations that arise from these connections. The individual, in her view, does not exist apart from the society, making individuals connected to past and future members of their community. In the next section, Thompson will explain how certain interests create the obligations found in Communitarianism. For more on Communitarianism, check out this video by, where philosopher Amitai Etzioni goes into more detail about the philosophy.

What are Lifetime‐Transcending Interests?

Here, Thompson gets down to the nitty-gritty of her theory. Think about what lifetime‐transcending interests you have while you read.

The scope of individual interest is not confined to concerns of a lifetime. Individuals have ideas about the good which are bound up with their hopes for their descendants and their regard for their forebears… I will argue that these interests, which I will call ‘lifetime‐transcending interests’, are the proper basis for an account of obligations in a transgenerational polity—an account that encompasses duties in respect to the past as well as duties to the future.

An interest, as I will understand it, is a valued object, activity or state of affairs around which clusters an interrelated set of desires, beliefs, hopes, predilections, motivations, attitudes and intentions. The interest gives these desires and predilections their point, and an interest, as an abiding state of a person, explains many of the things that she wants, does, demands or feels. Lifetime‐transcending interests have as their subject matter events, objects or states of affairs that either existed before the lifetime of the person who has the interest or will, or could, exist in the future beyond his lifetime. People who are concerned about how their children and grandchildren will fare after their death clearly have lifetime‐transcending interests… Such interests often motivate them to do certain things during their life: to make a will, to provide for their children, (p.34) to agree to become an organ donor, to engage in projects that are likely to bear fruit in the future after their deaths. Some lifetime‐transcending interests are necessarily post‐mortem: for example, my interest in how my body is disposed of. Other interests—though directed toward a future in which I will probably no longer exist—are not necessarily associated with my death. I may live long enough to know how my children fare in their adult life; I may even outlive them. There is no definite line between lifetime‐transcending interests and interests in states of affairs in the more distant future that I might live to experience…

…Lifetime‐transcending interests, as I understand them, can also be interests in past events before a person’s lifetime or in people of the past and their deeds… An interest in our nation’s history or in particular events in its history, an interest in the lives and deeds of our ancestors or predecessors count as lifetime‐transcending interests… These ‘past‐directed’ interests are also motivating. If we are interested in events in our nation’s history, we may desire to learn more about them, to teach children about them, to be faithful to them, to demand rectification for wrongs that we believe were done to the people of our nation in the past, and to participate in projects that continue our history in a particular way.

The Selfishness Objection

Some Background

That living a meaningful life involves having lifetime‐transcending interests is strongly supported by some philosophers. Charles Taylor thinks that individuals find a moral orientation and meaning for their activities by subscribing to a higher good—by establishing a connection with something universal and eternal, such as justice, God, aesthetic beauty or knowledge, that makes them part of something larger than their own lives . An ideal makes individuals part of something larger than their own life not only because it encourages them to be become concerned with the good of others but also because it motivates them to work or hope for a result that will probably not be achieved in their own lifetimes, and it connects them with those who have worked to achieve the ideal in past generations. Ernest Partridge argues that those who have no concerns that transcend their lifetimes are living impoverished lives. ‘Self‐transcendence’, as he calls it, gives meaning to our lives and projects, especially when we face the fact of our own mortality.

The Objection

Partridge fears that this argument is less than conclusive because it does not eliminate the possibility that people might live satisfactory lives that contain no objects of interest that do not relate to themselves and their lifetime experiences. The miser cares about money for the sake of his experience of owning it, and not for what objective values it might serve. A millionaire art collector may buy a valued painting not because he cares about its continuing value as a work of art but because he gets pleasure from locking it away from the gaze of others and keeping it for himself.

A Response

However, Partridge assumes that lifetime‐transcending interests have to be altruistic and that people must be conscious of what all of their interests are. The millionaire would not get satisfaction from owning great works of art and denying them to the public gaze if he did not believe in the value of these works as important contributions to an artistic heritage. Even if he gets satisfaction only from denying them to others, he is nevertheless riding piggyback on the lifetime‐transcending interests of others. He has to care that people value and want to preserve their artistic heritage. If they ceased to value it then locking his treasures away would be a meaningless act. He has perverse lifetime‐transcending interests of his own. Misers gloat over money and not, like magpies, over brightly coloured pieces of string. They seem, in other words, to have an objective interest in the people of their society using money as a traditional and persisting standard of value, now and into the future.

So it is difficult to imagine how someone can live a meaningful life without any kind of lifetime‐transcending interests.

Double Duty: Obligations to the Past and Future

The next move Thompson makes is to argue that we have duties to other generations, both past and future members of our communities. She references lifetime‐transcending interests to show why these obligations must be upheld.

I will argue that we ought to accept the existence of obligations in respect to the deeds and wishes of our predecessors. I will argue, first, that lifetime‐transcending interests of certain kinds can explain why we have duties in respect to the dead.

Let us consider a duty to the dead that many people affirm: the duty to avoid harming someone’s posthumous reputation through malicious slander. Most philosophers assume that the only way to justify the existence of such a duty is to establish that it is possible to harm the dead. But this idea, though some have defended it, is extremely problematic. An appeal to lifetime‐transcending interests that people had before their deaths provides another, less problematic way of explaining why survivors can have obligations in respect to their predecessors.

There are two principal reasons why people with such interests would care about their posthumous reputations.

First of all, they are likely to be concerned about the harm that could be done after their death to their objectives, projects, values, and the people they care about. Since slander can harm a person’s family or community or cause her works or ideals to become objects of ridicule, she will be predisposed to demand that her survivors not allow this to happen. This is not the same as demanding that her survivors care about the same things that she does, or that they carry on her projects or uphold her ideals. It is a demand that they not undermine or destroy the objects of her lifetime‐transcending interests by inventing or broadcasting malicious untruths.

The second reason is that people are likely to want their efforts, accomplishments, and objectives to be properly appreciated after their death by those whose opinion they respect and by the groups and institutions to which they have tried to make a contribution. Having the respect of others is for most people central to a meaningful existence, and slander to a person’s posthumous reputation would frustrate her desire to have her projects and endeavours respected by making her labours or intentions objects of ridicule and disrespect.

… If a person thought that her posthumous reputation would be vulnerable to those who would have no compunction against telling malicious lies for their own gratification or profit, she could not with confidence pursue lifetime‐transcending interests or believe that what she did would make a contribution or have a chance of being appreciated… An important dimension of human activity and aspiration would be undermined or diminished, thus diminishing the ability of a person to live a meaningful life.

Argument

Argument Breakdown

Thompson is arguing that we have obligations to the dead. But how exactly does she do this? Let’s break it down:

- We have a duty to encourage meaningful lives.

- If someone thought that their posthumous reputation would be sullied after their death, then they would not pursue lifetime‐transcending interests.

- If someone does not pursue lifetime‐transcending interests, then they are missing out on a key aspect of a meaningful life.

- Therefore, we have a duty to uphold the posthumous reputations of the dead

People with lifetime‐transcending interests care about their posthumous reputations. They care about them for two reasons: they do not want their values, goals, and people they care about to be harmed via slander and they want the pursuits of their goals to continue These lifetime‐transcending interests of certain kinds can thus explain why we have duties in respect to the dead.

Thought Experiment

Thought Experiment 1: The Compliant Atheist

Thought Experiment 1: The Compliant Atheist

-

A Proper Burial

-

A Duty to the Dead

-

(Connection): Application: Climate Change

This thought experiment tackles our obligations to the lifetime‐transcending interests of those who have just died.

Suppose Aunt Mabel is a fundamentalist Christian and wants her body to be buried with proper Christian ceremony with all of its organs intact. I, her only surviving relative, am an atheist who believes that bodies should be cremated without ceremony after all their useable organs have been donated to save the lives of others. It can be argued that when Aunt Mabel is dead she won’t care what is done with her body.

As an atheist, it is true that I have no lifetime‐transcending interest in being given a Christian burial with all my bodily organs intact (quite the contrary). But I do have an interest in how my body is disposed of (being a strong supporter of organ donation), and think it reasonable to demand that my request be honoured by my successors… So I have reason to support and act according to a transgenerational practice which requires survivors in most circumstances to dispose of the bodies of the dead according to the wishes that they expressed before death.

Thompson seems to lay out an argument here that goes like this: I will want others to respect my wishes after death, so I must respect the wishes of others (even if they go against my values). Sounds like this famous rule to me. Check out this podcast for a real-life example about how the wishes of those long dead still affect us today.

Many climate advocates cite climate change as one of the key reasons for taking intergenerational justice seriously, especially as we make decisions now that will affect future generations. On the campaign trail for the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Pete Buttigieg, former South Bend mayor, used the idea of intergenerational justice often to encourage voters to care about investments in green energy. You can read more about his campaign here.

Thought Experiment

Thought Experiment 2: Why You Should Care About Old Buildings

Thought Experiment 2: Why You Should Care About Old Buildings

-

Saving Historic Architecture

-

A Duty to Heritage

Suppose that in our city past generations have put a lot of money and effort into preserving and maintaining buildings which are associated with our early history and have made it clear that they regard them as an inheritance for future generations. However, most people in our generation are not interested in this inheritance and would prefer to use the sites on which the buildings stand for other, more productive purposes: housing, shopping malls, etc. Our city council, with our overwhelming support, decides to knock the buildings down and put up the kind of structures we currently prefer. By the time that the next generation comes to maturity the historic buildings are all gone.

Think about the lifetime transcending interests of the past members. How do you decide what to do? What justifications do you have for your choice? Click on the next tab to see Thompson’s answer.

By… destroying the historic buildings successors have been deprived of an opportunity to value and maintain a heritage. If heritage is of value to individuals, then these actions count as doing harm even if people do not suffer from their deprivation.

Just as we suspected, Thompson brings in the interests of the past members to argue that our actions can do them harm. Interestingly, she also describes how failing to comply with the past members’ desires also affects future generations. The two often go hand in hand.

TLDR;

Here’s a summary for the road:

By appealing to lifetime‐transcending interests to justify obligations we accomplish a number of objectives. First of all, we establish that members of communities have obligations in respect to their predecessors and that there is a way of determining what these are. Second, we show that members of communities have a moral interest in maintaining practices and institutions which enable legitimate lifetime‐transcending demands to be made and fulfilled. This moral interest does not exist merely because present people happen to think that their lifetime‐transcending demands ought to be fulfilled. Because they have moral reasons for making the demands that they do, they are entitled to insist that practices and institutions supporting the fulfilment of morally important lifetime‐transcending demands ought to be valued by future as well as present generations. Members of a community have moral reasons to regard their fellows, past, present and future, as sharing a common good—namely, practices of making and fulfilling lifetime‐transcending demands and the institutions that support these practices. The existence of these goods, and the particular obligations that arise from them, provide a vindication of the communitarian point of view. By being committed to maintain practices that require each generation to fulfil the morally legitimate demands of its predecessors the generations of a community are bound together in relationships of cooperation and have the obligations that follow from these relationships.

Want to Know More About Intergenerational Justice?

Check out John Rawls and Melissa Lane, who both write about intergenerational justice using the work of ancient philosophers.

This digital essay was prepared by Margaret McGreevy from the University of Notre Dame.

Potential Main videos:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gKA4JjkiU4A&ab_channel=AmitaiEtzioni

- This is the video also linked above

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCWU_7OdtkM&ab_channel=TheOxfordUniversityPoliticsBlog

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lT_ysth97zw&ab_channel=TEDxTalks

- These two are kinda boring but on topic

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eRLJscAlk1M&ab_channel=PrinceEa

- Kinda cheesy but more interesting; climate change angle

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAJsdgTPJpU&ab_channel=PBSNewsHour

- Climate change angle