Gregory Kavka “The Futurity Problem”: Obligated to the Future?

Gregory Kavka lived from 1947-1994, studying philosophy at Princeton University and the University of Michigan before travelling West to teach at the University of California at Irvine. A political philosopher who wrote extensively on Hobbes and nuclear deterrence, Kavka’s work is internationally admired. In particular, his book on Moral Paradoxes of Nuclear Deterrence helped establish the morality of nuclear deterrence as a new subfield in applied ethics.

In 1978, Kavka wrote the following essay called “The Futurity Problem” which was published in Obligations to Future Generations. The book’s collection of essays centers around the questions of “whether and to what degree it can be morally incumbent on us to make sacrifices to bring happy people into the world or to avoid preventing them being brought into the world.” In a world with diminishing resources, population growth, and environmental risks, the ideas proposed by Kavka and others in this book are frequently and extensively discussed today.

You can read a PDF of the text here if you prefer to work through that. Note, though, that this link is to the full text while the digital essay only covers specific excerpts from p. 186-202.

Key Concepts

- Futurity

- Temporal Location

- Contingency

The Futurity Problem

Kavka begins his essay by laying out the core debate: pessimists believe that within a few generations, the world will face extreme shortages of food, clear air, fossil fuels, and other goods essential to human survival; optimists, though, trust that modernisation will help check the increasing rates of consumption and support resource regeneration in a way that prevents such a catastrophe. Kavka assumes the position of the pessimist and poses the following question:

- Are we morally obligated, in order to prevent impending catastrophe for mankind, to impose strict limits on population growth, pollution, and resource use, at the cost-to many of us-of a significant decrease in our material standard of living and our freedom to have large families?

To begin answering this question, Kavka focuses on the problem of determining whether future people are morally different from present people to the extent that they should not be regarded as moral equals. The following excerpt covers his initial response and the layout of the rest of the essay:

- Suppose that we are obligated to aid desperately needy strangers who are now alive, even at substantial cost to ourselves and our friends. If the needs and interests of future people are as important, morally speaking, as those of present people, it would apparently follow that we are obligated to make substantial sacrifices, if necessary, to prevent future strangers from being desperately needy.

…[I]nstead of trying to prove that we are obligated to sacrifice for future generations, I seek only to establish the more modest conclusion that if we are obligated to make sacrifices for needy present strangers, then we are also obligated to sacrifice for future ones. We may arrive at this conclusion by considering, and rebutting, three sorts of reasons that might be offered for not giving the interests of future people equal consideration with those of present people: the temporal location of future people, our ignorance of them, and the contingency of their existence.

I. The Temporal Location of Future People

The first of Kavka’s points, he presents in the following section his argument as to why temporal location does matter in the moral consideration of future people.

The most obvious difference between present and future people is that the latter do not yet exist. Does this difference in temporal location in itself constitute a reason for favoring the interests of present over future persons?

…[T]emporal location does make a difference to morality when that location is in the past. For surely, it would be absurd to give equal weight to the desires of living and dead persons. This, however, may be admitted without affecting the claim of equal status for future people. There are two main reasons for favoring the desires of the living over those of the dead. First, nearly all of the desires of the dead concerned matters in their own lifetimes that are now past and cannot be changed. Second, consider those desires of persons now dead that were directed toward future states of affairs that living people might still bring about. Since the persons having had those desires will not be present to experience satisfaction in their fulfillment or disappointment in their non-fulfillment, it is reasonable to downgrade the importance of these desires (and perhaps ignore them altogether) in our moral decision making. Now, it is clear that neither of these two reasons applies to the desires of future people. We are in a position to act to make it more likely that many of the desires of future people will be satisfied, and future people will be around to experience the fulfillment or non-fulfillment of their desires. … It may be concluded that while there are sound reasons, when deciding whose desires to satisfy, to favor present over past people, the difference in their temporal location does not constitute a reason for favoring present over future people.

Argument

Using the Past to Understand the Future

Kavka compares the past to the future to establish the moral worth of future people. Let’s break down his central argument:

- We may discount the desires of people at other temporal locations if (a) it is impossible for us to satisfy their desires, or (b) it is impossible for them to experience the fulfillment or non-fulfillment of their desires.

a. Jim cannot satisfy the desire of his great grandmother who wanted to own a horse and buggy. Lucy is not obligated to satisfy the desire of her late grandfather who wanted all his descendents to live in Connecticut. - It is possible for us to satisfy the desires of future people.

a. Bill can provide for his future grandchildren. - Future people will experience the fulfillment or non-fulfillment of their desires.

a. Bill’s future grandchildren will be satisfied when they receive Bill’s inheritance. - All else being equal, we should account for the desires of future people.

II. Our Ignorance of Future People

The second point Kavka will tackle is the objection that we cannot possibly know what future people want, so therefore we have no obligations toward them. While this idea may appear to counter the previous argument, Kavka refutes the entire claim by saying that there are always some necessary and general desires that we know future people will want. As a result, we are not as ignorant of them as we would perhaps think.

II. Our Ignorance of Future People

-

The Objection of Ignorance

-

Thought Experiment: The Power of the Butterfly

-

Kavka’s Response

-

An Analogy to a Young Man

While the temporal location of future people is, in itself, not a reason for discounting their interests, other factors resulting from their temporal location might be. In particular, it could be argued that our ignorance of future people renders us less able to promote their interests than those of present people. For future people are not around to tell us what their desires are (or will be). Also, our ability to shape future events generally decreases as they become temporally more distant, so it may be thought that we would be less able to satisfy the desires of future than of present people, even if we knew in detail what those desires will be.

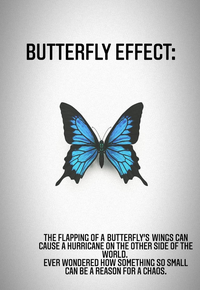

Kavka says that “our ability to shape future events generally decreases as they become temporally more distant”–is this truly the case? Perhaps in some ways it is, but let’s consider the idea of the Butterfly Effect: the notion that one small change can result in large differences later on. The example behind this idea’s name is that a butterfly flapping its wings one place on the planet can cause a hurricane somewhere else.

Apply this to Kavka’s statement. Do we perhaps have more influence over the future than we think? Reflect on moments in human history that have changed the world: the first airplane, nuclear bomb, or march for civil rights. What one person does in big or small ways does seem to affect the future in unimaginable ways sometimes. What do you think?

Does this relative ignorance of what future people will want, and how to get it for them, justify us in paying less attention to their interests in decision making? I am doubtful that it does to any substantial degree. For we do know with a high degree of certainty the basic biological and economic needs of future generations-enough food to eat, air to breathe, space to move in, and fuel to run machines. The satisfaction of these needs will surely be a prerequisite of the satisfaction of most of the other desires and interests of future people, whatever they may be…

What I am suggesting is that we view our ignorance of the interests of future people as being analogous to a young adult’s ignorance of the desires and interests he will have in old age, say, after retirement. It is unlikely that a young adult will know in detail the goals and desires he will have in forty years: whether, for example, he will wish to spend his time traveling, doing volunteer work, or drinking beer. However, he can believe with a high degree of confidence that his important needs and interests will include good health, adequate food and shelter, and security for his loved ones. And there are definite things he can do now that will make it more likely that these needs will be met: saving or investing a portion of his income, eating properly, exercising regularly, etc. Rational prudence would advise him to do these things, despite his ignorance of the details of the desires he will have when old. Similarly, morality advises us to take steps to insure an adequate supply of resources for future generations, despite our ignorance of the details of the desires that future people will have…

III. The Contingency of Future People

Objection

The Contingency Objection

Kavka now turns to another objection against considering future people in our moral calculus–they simply might not exist. Additionally, the choices that present people make can determine their existence (or lack thereof) entirely. To walk through this objection and his response, Kavka articulates a couple of analogies to help ground the discussion:

Having rejected the temporal location of future people and our ignorance of them as substantial reasons for downgrading the importance of their interests, we must now deal with the most perplexing and least tractable feature of future people–their contingency. The trouble with future people, we might say, is not that they do not exist yet, it is that they might not exist at all. Further, what and how many future people will exist depends upon the decisions and actions of present people. To see how this existential dependence of future persons on the decisions of present ones affects the moral relationship between the two, let us consider [an analogy]…

A …clos[e] analogy to the situation of the present generation with respect to future generations involves a poor couple that has some children and is planning to have more. Should they: treat the interests of their prospective children on a par with those of their existing children, by husbanding resources that could be used by the latter? Not if this would cause the existing children to suffer serious deprivation. For in that case, they should simply not have any more children.

[This] example suggest[s] that, under conditions of scarcity, resource distributors have reason to show preference for existing resource consumers (e.g. people) over future resource consumers whose very existence is dependent upon the distributor’s decisions and actions. It is important, however, not to misunderstand the nature of these reasons or the kind of preferences they support. Under scarcity, there seems to be reason to meet the needs of existing consumers rather than bringing into existence too many new consumers who will make demands on scarce resources. This does not mean, however, that consumers that one assumes or knows will exist are less important or less worthy of receiving resources than those presently existing. To see this, suppose that the parents in our example know they will not change their mind about having more children, even if they save no resources to care for them. Under these circumstances, they ought to give their prospective children equal consideration with their present ones.

Let’s break down this analogy.

Suppose Susie and Bart have just started their new family. While neither make very much, they are diligent thrifters and savers to live comfortably. After their first two children, though, Susie develops a medical condition that makes any future childbirths risky. She and Bart are now unsure of whether they will pursue more children even though they had initially hoped for a large family.

Under these conditions, Kavka suggests that Susie and Bart are under conditions of scarcity–they are at their financial and health limits at the moment and any further children would threaten that equilibrium. As a result of those conditions, they should focus on meeting the needs of their existing two children and Susie’s health rather than have more children who will make demands on scarce resources.

If, however, Susie and Bart know that they will take the chance with having more children, supposing for instance that there will be a remedy for Susie’s condition or the risks won’t manifest, then their calculus changes. Their future children take on the same moral weight as their existing children and they should prioritize them respectively (like equally investing in college funds for all, future and existing children alike).

These examples show how the “contingent” aspect of future people really depends on how determined present people are in bringing them about; the moral status of future people can be elevated or dismissed depending on that certainty.

The Implications

The implications of these examples with respect to our relationship to future generations are as follows. Suppose, following the pessimists, that we (i.e. those presently living) cannot (i) consume as much as we want and could, and (ii) have as many children as we want and could, and (iii) still leave sufficient resources to take care of the needs of future people. Then, we must either consume less or produce fewer children, if we are to leave enough for future generations. Now, our examples do not indicate that the contingency of future people in any way warrants our abandoning the goal of conserving resources adequate to the needs of future people. What they do suggest is that producing fewer future people (than we could), so as to allow us both to provide for the needs of those future people who are produced and still to consume what we want, would be a morally viable option.

Argument

The Either/Or

- We should leave enough resources for future generations.

- At the current rate of consumption, present people would not leave behind enough resources.

- At the world’s current rate of reproduction, present people would not leave behind enough resources.

- If we are to leave enough resources for future generations, we must either consume less or produce fewer children.

Controversial?

Although his argument allows for a choice–we must either consume less or produce fewer children–Kavka focuses on the moral viability of the latter option: producing less children to sustain our current levels of consumption in a way that still benefits future generations. This may be a controversial position depending on your point of view.

One position would argue that we should curb our resource consumption and live less extravagantly rather than reduce the numbers in future generations to maintain our lifestyle. Others might say that slowing population growth is the more efficient and easier way to guarantee future generations have enough to live on rather than trying to alter the mass consumerism in force today. These are only some of the potential reasons a reader might have in leaning towards one side of the dichotomy, but it’s important to acknowledge both approaches.

Kavka’s concerns here focus on the individual level–what one person owes to the future. Another approach, however, is understanding this issue from a societal level–what corporations or states owe to the future. While this is an important extension of the conversation, Kavka will remain focused here on the individual.

In the proceeding excerpt, Kavka addresses the assumption in his first premise, namely that there will be future generations for us to be obligated to. If there are no future generations, then we have no moral obligations to preserve resources for them. This position and his response will be the next section he covers in-depth.

…It was suggested above that limiting the size of the next generation to allow more consumption in this generation would not be an objectionable policy. But suppose this policy were carried to its farthest extreme. Suppose, that is, that everyone now living voluntarily agreed to forego the pleasures of childbearing and agreed to undergo sterilization, so that they could live out their lives consuming and polluting to their heart’s content without worrying about the effects on future generations. …Would there be anything morally wrong about our generation (or some later generation) doing this? Or, to put the matter somewhat differently, does a moral person have any reason to care that the human race survive?

IV. The Survival of the Human Species

Setting aside their particular desires to have and raise children, why shouldn’t present people simply refrain from producing future people, so that they can live out their lives consuming and polluting at will? … would it be morally wrong for present people to act collectively in this way if they freely chose to do so? One might be tempted to object to such action on the grounds that it would be unfair to future generations. But this objection flounders in the face of the fact that if the action were successfully carried out, there would be no future generations to have been treated unfairly by it. Leaving fairness aside, the central question becomes whether we, as moral persons, have any reason to care about the survival of our species. … I should like to set out my reasons for thinking that we do.

It is generally acknowledged that human life has value, and hence the lives of existing people are, with rare exceptions, worth preserving. If we dare to venture the question of why human life is valuable and worth preserving, the answers we receive-religious answers aside-are likely to fall into three categories. First, there are answers that explain the value of life in terms of the pleasures contained therein. Second, it may be held that certain human experiences or relationships (e.g. loving another person) are valuable in themselves, beyond the pleasures they contain, and it is the having of such experiences (or the possibility of having them) that makes human life valuable. Third, it may be thought that the value of human life is to be found in the human capacity for accomplishment, the fact that human beings set and achieve goals, and exercise and develop various complex capacities. What is of interest here is that, whichever of these views of the value of human life (or combination of such views) one adopts, it turns out that the lives of future people would almost certainly possess the properties that make the lives of present people valuable, and hence would be valuable themselves. This seems to be a reason for creating such lives; that is, for bringing future people into existence.

Argument

The Value of People

- If human lives have value, they are worth creating.

- An artist has a vision for her next painting, so she should create it because of its future value in beauty.

- Outside of religious reasons, value can be determined by the amount of pleasure in that life, the experiences or relationships cultivated during it, or the capacity for achievement.

- Jackson the millionaire would have a valuable life based on pleasure. Jackson the community member would be valuable for his relationships. And Jackson the doctor would be valuable for his contributions to science.

- Future people will certainly possess at least one of those valuable properties.

- Future people will be capable of pleasure, experiences, relationships, and/or achievement.

- The lives of future people have value and are worth creating.

Connection

An Analogy to the Individual

Kavka builds on his argument that the future of the human species should be preserved by making a comparison between the life of the species and the life of an individual. The following excerpt articulates why we should prefer that the species continues:

…The notion that our species should be preserved gains additional support from an analogy that can be constructed between the life of the species and the life of an individual. Imagine an individual choosing between two strategies for living. First, living to the fullest for a few years, consuming and creating at a rapid rate but dying soon as a result. Second, consuming and creating at a moderate pace in the near future and living a long life of progressively greater accomplishments, with total accomplishments far surpassing those that could be attained in a short life. Choosing the short life in such circumstances would be analogous to our generation’s cutting out reproduction in favor of unlimited present consumption. Choosing the long life would be analogous to our generation’s limiting consumption and growth so that the species can survive and progress for a very long time. In the individual case, we are strongly inclined to approve the choice of the longer life, to have greater respect for the individual making that choice than for the individual who chooses the short but sweet life. This suggests, by analogy, that we should prefer a longer life of increasing accomplishment for mankind, to having human history cut short to facilitate present consumption.

…To summarize, there seem to be two main sorts of reasons, that moral persons will appreciate, for wanting the human species to survive. First, human life has value and is generally a good thing to those possessing it. Second, the continuation of our species will very likely mean the continuation of its collective artistic, intellectual, and scientific accomplishments. Further, certain features of the analogy between the life of an individual and the life of the species suggest the reasonableness of the preference for continuation over termination of the species. Taken together, these considerations suggest that a moral person should not be indifferent to mankind’s survival.

V. Aid Between Generations

In this final section, Kavka considers how we should approach the distribution of resources between generations. Setting aside our bias to our own generation, Kavka draws upon the philosophy of John Locke to establish the fair distribution of resources in the turning over of each generation.

John Locke supposes that men in the state of nature are moral equals and that God has given to them, in common, the use of the earth and its resources. He claims that, under these conditions, an individual may fairly appropriate land for his own use without belying the status of his fellows–provided that he (i) uses rather than wastes what he appropriates and (ii) leaves “enough and as good for others“. Locke justifies the latter condition on the ground that one who appropriates a resource but leaves enough and as good for others, leaves others as well off as they were prior to the appropriation. Hence, they are not injured by his act and have no complaint against him. Given that present and future persons are moral equals with equal claim to the earth and its resources, Locke’s analysis can be extended to apply to the problem of generational resource use. Accordingly, we say that a generation may use the earth’s resources provided that it (i) does not waste them (i.e. uses them to satisfy human interests) and (ii) leaves “enough and as good” for future generations. In the spirit of the justification Locke offers for his second condition, I interpret this to mean that, in this context, the generation in question leaves the next generation at least as well off, with respect to usable resources, as it was left by its ancestors… Since it is individuals, and not generations per se, that are regarded as equal, I understand the relevant measure of usable resources to be relativized to population. This means that if a given generation insists on having more than one descendant per capita, it is to aim at leaving proportionally more total resources.

Main Idea: Leaving the Next Generation No Worse Off

Kavka uses Lockean philosophy to establish that every generation is obligated to manage its consumption appropriately in order to leave as many resources as it originally received for the next generation. In other words, every future individual in the next generation should be no worse off after the current generation’s consumption than each of them were before.

Objection

An Impossible Standard?

It might at first appear impossible that any generation live up to the Lockean standard. For questions of waste aside, how could a generation use any resources at all and leave even an equal number of descendants with as many resources as they themselves inherited? The question is readily answered by noting that some physical resources are renewable or reusable, and that knowledge–especially scientific and technological knowledge–is a usable resource that grows without being depleted and enables us to increase the output of the earth’s physical resources. Thus, what the Lockean standard recommends is that each generation use the earth’s physical resources only to the extent that technology allows for the recycling or depletion of such resources without net loss in their output capacity…. If all succeeding generations abided by it, mankind could go on living on earth indefinitely, with living standards improving substantially from generation to generation, once world population were stabilized…

Conclusion

I close with a brief summary of my conclusions. The temporal location of future people and our comparative ignorance of their interests do not justify failing to treat their interests on a par with those of present people. While the contingency of future people does justify granting priority to the needs of existing people, it does so only in the sense of warranting population limitation as a means of limiting the total needs of future generations. However, population limitation carried to the utmost extreme, i.e. the end of the species by collective decision not to reproduce, would not be morally justified… Finally, the equal moral status of present and future persons suggests that our generation should, ideally, aim collectively at leaving our descendants a planet as rich in usable per capita resources as that we have inherited from our ancestors.

Want to Know More?

Interested in reading more on the Futurity Problem and our obligations to future generations? Preview the other essays in Obligations to Future Generations here.

Acknowledgements

This essay was prepared by Julia French from the University of Notre Dame.

Main Video Recommendation

Human Population Growth – Crash Course Ecology #3 (CrashCourse)

Explains background on WHY human population has grown exponentially (10 min)

Dear Future Generations: Sorry (Prince Ea)

Spoken word apology to future generations if consumerism not checked while also a call to action (6 min but poem ends at 4:45)