God and Suffering: Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Introduction to Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Introduction to Fyodor Dostoyevsky

-

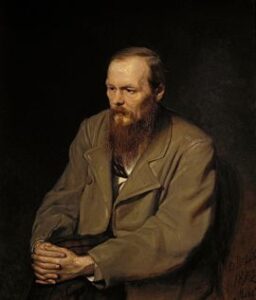

Who is Fyodor Dostoyevsky?

-

The Problem of Evil: An Overview

-

The Problem of Evil Argument Outlined

Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881) was a Russian novelist, journalist, and philosopher whose work explores the political, social, and spiritual dimensions of human psychology. He is considered one of the greatest psychological novelists and began the genre of existentialist literature. Major themes of his work focus on the dark aspects of human nature, attempting to understand the pathological states behind evil actions and individuals. He was influenced by prominent philosophical and literary figures like St. Augustine, Plato, Immanuel Kant, William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Edgar Allen Poe, and many others. He was also a major influence on two philosophers we cover in this course: Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre.

One particular work by Dostoyevsky is The Brothers Karamazov, which explores major theological and philosophical themes, such as the origin of evil, the nature of freedom, and humanity’s craving for faith. The novel features four sons of a neglectful father wrangling with these issues. Two major brothers are Aloysha, the youngest son who attempts to live life as a Christian, and Ivan, the intellectual middle brother who is skeptical and antagonistic towards the existence of God. In this class, we will examine Book V, Chapter IV of The Brothers Karamazov, entitled “Rebellion”. The chapter concerns a dialogue between Ivan and Aloysha. Ivan challenges the existence of God due to the endless and unnecessary suffering in the world, something that makes the paradise religion promises after death meaningless. In short, Ivan is describing the Problem of Evil, a key concept for today’s class. You can find a link to the document here if you prefer to work through that.

Before diving into the text, let’s go over some key concepts and definitions. The reading centers around the Problem of Evil, which is an objection to the existence of God alleging that the evil and suffering in the world is contradictory to belief in an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God. The argument states that no all-powerful and good Creator would allow unnecessary suffering in the world; therefore, because unnecessary suffering does exist (natural disasters, disease, murder, etc.), that Creator cannot exist.

The Problem of Evil has an expansive history in theology and philosophy. The Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) provides a suitable explanation of the argument, arguing that any explanation of evil coinciding with God’s existence necessarily means God is not an all-powerful or good Creator:

- “Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then where does evil come from?”

Moreover, the French writer and philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778) satirizes religion in his poetic defense of the Problem of Evil:

Unlucky mortals! O deplorable earth!

All humanity huddled in fear!

The endless subject of useless pain!

Come philosophers who cry, “All is well,”

And contemplate the ruins of this world.

…As the dying voices call out, will you dare respond

To this appalling spectacle of smoking ashes with,

“This is the necessary effect of the eternal laws

Freely chosen by God”?

Seeing this mass of victims, will you say,

“God is avenged. Their death is the price of their crimes”?

What crime, what fault had the young committed,

Who lie bleeding at their mother’s breast?

We can see the premise-conclusion form of the argument below.

(1) God is all-powerful and morally perfect.

Example: Most monotheistic depict God as a Creator who is all-powerful, all-knowing, and good.

(2) Any being that’s all powerful and morally perfect would prevent unnecessary suffering in the world.

Example: An all-powerful being with perfect moral knowledge would easily recognize injustice. Because that being has the ability to stop that injustice, it has a moral duty to do so.

(3) There is unnecessary suffering in the world.

Example: Natural disasters, disease, and other types of evil in the world describe a system of unnecessary suffering.

(C) God does not exist.

Argument

We Cannot Love Thy Neighbor

Dostoyevsky begins the chapter with Ivan responding to Jesus’s command to love one’s neighbor. Ivan argues that it is impossible to unconditionally love one’s neighbor because of the way humans approach suffering. Note how Ivan characterizes humanity. Does he think humans are inherently evil? How does that relate to the Problem of Evil and God’s existence?

“I must make an admission,” Ivan began. “I never could understand how it’s possible to love one’s neighbors. In my opinion, it is precisely one’s neighbors that one cannot possibly love. Perhaps if they weren’t so nigh … I read sometime, somewhere about ‘John the Merciful’ (some saint) that when a hungry and frozen passerby came to him and asked to be made warm, he lay down with him in bed, embraced him, and began breathing into his mouth, which was foul and festering with some terrible disease. I’m convinced that he did it with the strain of a lie, out of love enforced by duty, out of self-imposed penance. If we’re to come to love a man, the man himself should stay hidden, because as soon as he shows his face—love vanishes.”

“Well, I don’t know it yet, and I cannot understand it, nor can a numberless multitude of other people along with me. The question is whether this comes from bad qualities in people, or is inherent in their nature. In my opinion, Christ’s love for people is in its kind a miracle impossible on earth. True, he was God. But we are not gods. Let’s say that I, for example, am capable of profound suffering, but another man will never be able to know the degree of my suffering, because he is another and not me, and besides, a man is rarely willing to acknowledge someone else as a sufferer (as if it were a kind of distinction). And why won’t he acknowledge it, do you think? Because I, for example, have a bad smell, or a foolish face, or once stepped on his foot. Besides, there is suffering and suffering: some benefactor of mine may still allow a humiliating suffering, which humiliates me—hunger, for example; but a slightly higher suffering—for an idea, for example—no, that he will not allow, save perhaps on rare occasions, because he will look at me and suddenly see that my face is not at all the kind of face that, he fancies, a man should have who suffers, for example, for such and such an idea. And so he at once deprives me of his benefactions, and not even from the wickedness of his heart.

Key Principle

Loving Others and Suffering are Incompatible

Loving Others and Suffering are Incompatible

-

We Cannot Love Others Argument Outlined

-

Connection to the Problem of Evil

Ivan is attempting in this passage to convince you that suffering precludes us from unconditionally loving others. He attempts this through two arguments that work together to demonstrate that different types of suffering are not universally recognized and that humans don’t always stop the suffering of others when given the chance. His argument is broken down below.

(1) Jesus’s command to love others unconditionally necessitates that we have the ability to perform the command.

Example: Giving anyone a command or rule implies that they have the ability to do so. If Joe tells Greg to finish a report, Greg must be able to finish the report or have the capacity to learn how to finish it.

(2) Loving others unconditionally means preventing all unnecessary suffering.

Example: Loving others means caring and supporting them. If Sophia sees Jeffrey drowning in the lake, she has a moral obligation to help him because as a fellow person, Jeffrey is entitled to unconditional love.

(3) People have differing perceptions of suffering, making it difficult to determine when one should intervene to stop another’s suffering.

Example: Just like happiness, everyone has a different capacity for suffering. For most, lifting 350lb weights would be an enormous struggle and likely lead to unnecessary suffering. One should intervene to stop that suffering. However, some are capable of lifting this weight and actually participate in that struggle to become stronger. One should not intervene to stop that suffering. Therefore, lifting the weights is suffering for some and not for others, which makes it difficult to determine when to stop the suffering.

(4) Even if we can discern if one is truly suffering, some allow that suffering to continue for personal benefit.

Example: Mark works in construction, a labor-intensive job that often puts strain on his body and health issues. His employer, Alex, can see that the jobs he gives Mark is causing unnecessary pain, but he continues to assign Mark work because it delivers profits to Alex.

(C) Suffering precludes us from unconditionally loving others.

Ivan uses his indictment of the Great Commandment to set up his main argument that the unnecessary suffering in the world means that God cannot exist and any reward in the afterlife is not worth the struggles of living. He accomplishes this by focusing on the experiences of children, who Ivan believes are the most innocent individuals in the world. They have not been corrupted by humanity and have not indulged in sin like adults, yet they still experience immense suffering in the world. Read Ivan’s justification for focusing on children for his argument below.

I meant to talk about the suffering of mankind in general, but better let us dwell only on the suffering of children. First, one can love children even up close, even dirty or homely children (it seems to me, however, that children are never homely). Second, I will not speak of grown-ups because, apart from the fact that they are disgusting and do not deserve love, they also have retribution: they ate the apple, and knew good and evil, and became ‘as gods.’ And they still go on eating it. But little children have not eaten anything and are not yet guilty of anything.

Do you love children, Alyosha? I know you love them, and you’ll understand why I want to speak only of them now. If they, too, suffer terribly on earth, it is, of course, for their fathers; they are punished for their fathers who ate the apple—but that is reasoning from another world; for the human heart here on earth it is incomprehensible. It is impossible that a blameless one should suffer for another, and such a blameless one! Marvel at me, Alyosha—I, too, love children terribly. And observe, that cruel people—passionate, carnivorous, Karamazovian—sometimes love children very much.

“I think that if the devil does not exist, and man has therefore created him, he has created him in his own image and likeness.”

Ivan uses three stories he has heard about the unnecessary cruelty dealt to children to make an emotional appeal for his argument. As you read their stories, consider how their unnecessary suffering might be used to argue against God’s existence, referring to the argument made in the introduction.

Thought Experiment

The Suffering of Children

The Suffering of Children

-

Richard the Reformed Murderer

-

The Flogged Daughter

-

The General and the Boy

Ivan describes a man named Richard, who had an unruly upbringing that ended in him stealing and murdering. Yet, his death is celebrated as a holy act when he accepts religion, seemingly forgetting his past evils and the suffering of his childhood. Ivan is condemning belief in God and the afterlife, arguing that one cannot ignore suffering done in the world. Does Richard’s faith excuse his actions? Are his parents forgiven for abandoning him?

I have a lovely pamphlet, translated from the French, telling of how quite recently, only five years ago, in Geneva, a villain and murderer named Richard was executed— a lad of twenty-three, I believe, who repented and turned to the Christian faith at the foot of the scaffold. This Richard was someone’s illegitimate child; at the age of six he was presented by his parents to some Swiss mountain shepherds, who brought him up to work for them. He grew up among them like a little wild beast; the shepherds taught him nothing; on the contrary, by the time he was seven, they were already sending him out to tend the flocks in the cold and wet, with almost no clothes and almost nothing to eat. And, of course, none of them stopped to think or repent of doing so; on the contrary, they considered themselves entirely within their rights, for Richard had been presented to them as an object, and they did not even think it necessary to feed him. Richard himself testified that in those years, like the prodigal son in the Gospel, he wanted terribly to eat at least the mash given to the pigs being fattened for market, but he was not given even that and was beaten when he stole from the pigs, and thus he spent his whole childhood and his youth, until he grew up and, having gathered strength, went out to steal for himself. The savage began earning money as a day laborer in Geneva, spent his earnings on drink, lived like a monster, and ended by killing some old man and robbing him. He was caught, tried, and condemned to death.

So then in prison he was immediately surrounded by pastors and members of various Christian brotherhoods, philanthropic ladies, and so on. In prison they taught him to read and write, began expounding the Gospel to him, exhorted him, persuaded him, pushed him, pestered him, urged him, and finally he himself solemnly confessed his crime. He repented, he wrote to the court himself saying that he was a monster, and that at last he had been deemed worthy of being illumined by the Lord and of receiving grace. All of Geneva was stirred, all of pious and philanthropic Geneva. All that was lofty and well-bred rushed to him in prison; Richard was kissed, embraced: ‘You are our brother, grace has descended upon you! ‘ And Richard himself simply wept with emotion: ‘Yes, grace has descended upon me! Before, through all my childhood and youth, I was glad to eat swine’s food, and now grace has descended upon me, too, I am dying in the Lord!’ ‘Yes, yes, Richard, die in the Lord, you have shed blood and must die in the Lord. Though it’s not your fault that you knew nothing of the Lord when you envied the swine their food and were beaten for stealing it (which was very bad, for it is forbidden to steal), but still you have shed blood and must die.’ And so the last day came. Limp Richard weeps and all the while keeps repeating: ‘This is the best day of my life, I am going to the Lord! ‘ ‘Yes,’ cry the pastors, the judges, and the philanthropic ladies, ‘this is your happiest day, for you are going to the Lord!’ And it’s all moving towards the scaffold, in carriages and on foot, following the cart of shame that is bearing Richard. They arrive at the scaffold. ‘Die, brother,’ they call out to Richard, ‘die in the Lord, for grace has descended upon you, too! ‘ And so, covered with the kisses of his brothers, brother Richard is dragged up onto the scaffold, laid down on the guillotine, and his head is whacked off in brotherly fashion, forasmuch as grace has descended upon him, too.

Ivan compares the act of beating a horse to make it go faster to the abuse experienced by a daughter at the hands of her parents. The parents are praised for their actions, as it seemingly produced a well-rounded child. Here, Ivan is arguing that the girl, innocent and not susceptible to sin, was dealt unnecessary suffering no afterlife can compensate for. He condemns the Creator for such a world where children are punished but adults, the true sinners, are lauded. Why is this suffering necessary? What does this say about an all-powerful and all-good God?

An intelligent, educated gentleman and his lady flog their own daughter, a child of seven, with a birch. The papa is glad that the birch is covered with little twigs, ‘it will smart more,’ he says, and so he starts ‘smarting’ his own daughter. I know for certain that there are floggers who get more excited with every stroke, to the point of sensuality, literal sensuality, more and more, progressively, with each new stroke. They flog for one minute, they flog for five minutes, they flog for ten minutes—longer, harder, faster, sharper. The child is crying, the child finally cannot cry, she has no breath left: ‘Papa, papa, dear papa!’ The case, through some devilishly improper accident, comes to court. The lawyer shouts in his client’s defense. ‘The case,’ he says, ‘is quite simple, domestic, and ordinary: a father flogged his daughter, and, to the shame of our times, it has come to court!’ The convinced jury retires and brings in a verdict of ‘not guilty.’ The public roars with delight that the torturer has been acquitted.

A little girl, five years old, is hated by her father and mother, ‘most honorable and official people, educated and well-bred.’ You see, once again I positively maintain that this peculiar quality exists in much of mankind—this love of torturing children, but only children. These same torturers look upon all other examples of humankind even mildly and benevolently, being educated and humane Europeans, but they have a great love of torturing children, they even love children in that sense. It is precisely the defenselessness of these creatures that tempts the torturers, the angelic trustfulness of the child, who has nowhere to turn and no one to turn to—that is what enflames the vile blood of the torturer. There is, of course, a beast hidden in every man, a beast of rage, a beast of sensual inflammability at the cries of the tormented victim, an unrestrained beast let off the chain, a beast of diseases acquired in debauchery–gout, rotten liver, and so on. These educated parents subjected the poor fiveyear-old girl to every possible torture. They beat her, flogged her, kicked her, not knowing why themselves, until her whole body was nothing but bruises; finally they attained the height of finesse: in the freezing cold, they locked her all night in the outhouse, because she wouldn’t ask to get up and go in the middle of the night (as if a five-year-old child sleeping its sound angelic sleep could have learned to ask by that age)—for that they smeared her face with her excrement and made her eat the excrement, and it was her mother, her mother who made her! And this mother could sleep while her poor little child was moaning all night in that vile place! Can you understand that a small creature, who cannot even comprehend what is being done to her, in a vile place, in the dark and the cold, beats herself on her strained little chest with her tiny fist and weeps with her anguished, gentle, meek tears for ‘dear God’ to protect her—can you understand such nonsense, my friend and my brother, my godly and humble novice, can you understand why this nonsense is needed and created? Without it, they say, man could not even have lived on earth, for he would not have known good and evil. Who wants to know this damned good and evil at such a price? The whole world of knowledge is not worth the tears of that little child to ‘dear God.’ I’m not talking about the suffering of grown-ups, they ate the apple and to hell with them, let the devil take them all, but these little ones!

In this last story, Ivan describes a young boy who suffers immensely for throwing a stone at a general’s dog. The general sends the boy to be hunted by his dogs, resulting in the child’s death. Ivan uses this story to convey the cruel and unusual punishments children suffer for the slightest sins, while the adults who sin in a much worse fashion continue to live well.

There was a general at the beginning of the century, a general with high connections and a very wealthy landowner, the sort of man (indeed, even then they seem to have been very few) who, on retiring from the army, feels all but certain that his service has earned him the power of life and death over his subjects. There were such men in those days. So this general settled on his estate of two thousand souls, swaggered around, treated his lesser neighbors as his spongers and buffoons. He had hundreds of dogs in his kennels and nearly a hundred handlers, all in livery, all on horseback. And so one day a house-serf, a little boy, only eight years old, threw a stone while he was playing and hurt the paw of the general’s favorite hound. ‘Why is my favorite dog limping?’ It was reported to him that this boy had thrown a stone at her and hurt her paw. ‘So it was you,’ the general looked the boy up and down. ‘Take him!’ They took him, took him from his mother, and locked him up for the night. In the morning, at dawn, the general rode out in full dress for the hunt, mounted on his horse, surrounded by spongers, dogs, handlers, huntsmen, all on horseback. The house-serfs are gathered for their edification, the guilty boy’s mother in front of them all. The boy is led out of the lockup. A gloomy, cold, misty autumn day, a great day for hunting. The general orders them to undress the boy; the child is stripped naked, he shivers, he’s crazy with fear, he doesn’t dare make a peep … ‘Drive him!’ the general commands. The huntsmen shout, ‘Run, run!’ The boy runs … ‘Sic him!’ screams the general and looses the whole pack of wolfhounds on him. He hunted him down before his mother’s eyes, and the dogs tore the child to pieces…! I believe the general was later declared incompetent to administer his estates.

Argument

Rejecting the Harmony

Distraught by the suffering he witnesses for innocent children, Ivan refuses to accept that the suffering is compensated by being rewarded in the afterlife. He argues that reward or punishment for suffering in this world does not diminish the suffering. The suffering happened and will always remain. Ivan asks why a just God would allow such harm? His only conclusion is to reject such events and simply accept that suffering is a cruel, unjustifiable aspect of life. You can read his thoughts below.

Is it possible that I’ve suffered so that I, together with my evil deeds and sufferings, should be manure for someone’s future harmony? I want to see with my own eyes the hind lie down with the lion, and the murdered man rise up and embrace his murderer. I want to be there when everyone suddenly finds out what it was all for. All religions in the world are based on this desire, and I am a believer. But then there are the children, and what am I going to do with them? That is the question I cannot resolve. For the hundredth time I repeat: there are hosts of questions, but I’ve taken only the children, because here what I need to say is irrefutably clear.

Listen: if everyone must suffer, in order to buy eternal harmony with their suffering, pray tell me what have children got to do with it? It’s quite incomprehensible why they should have to suffer, and why they should buy harmony with their suffering. Why do they get thrown on the pile, to manure someone’s future harmony with themselves? I understand solidarity in sin among men; solidarity in retribution I also understand; but what solidarity in sin do little children have? And if it is really true that they, too, are in solidarity with their fathers in all the fathers’ evildoings, that truth certainly is not of this world and is incomprehensible to me. I do understand how the universe will tremble when all in heaven and under the earth merge in one voice of praise, and all that lives and has lived cries out: ‘Just art thou, O Lord, for thy ways are revealed!’ It is not worth one little tear of even that one tormented child who beat her chest with her little fist and prayed to ‘dear God’ in a stinking outhouse with her unredeemed tears! Not worth it, because her tears remained unredeemed. They must be redeemed, otherwise there can be no harmony. But how, how will you redeem them? Is it possible? Can they be redeemed by being avenged? But what do I care if they are avenged, what do I care if the tormentors are in hell, what can hell set right here, if these ones have already been tormented? And where is the harmony, if there is hell? I want to forgive, and I want to embrace, I don’t want more suffering. And if the suffering of children goes to make up the sum of suffering needed to buy truth, then I assert beforehand that the whole of truth is not worth such a price. I don’t want harmony, for love of mankind I don’t want it. I want to remain with unrequited suffering. I’d rather remain with my unrequited suffering and my unquenched indignation, even if I am wrong. Besides, they have put too high a price on harmony; we can’t afford to pay so much for admission. And therefore I hasten to return my ticket. And it is my duty, if only as an honest man, to return it as far ahead of time as possible. Which is what I am doing. It’s not that I don’t accept God, Alyosha, I just most respectfully return him the ticket.”

That is rebellion

Alyosha said softly, dropping his eyes.

“Rebellion? I don’t like hearing such a word from you,” Ivan said with feeling. “One cannot live by rebellion, and I want to live. Tell me straight out, I call on you–answer me: imagine that you yourself are building the edifice of human destiny with the object of making people happy in the finale, of giving them peace and rest at last, but for that you must inevitably and unavoidably torture just one tiny creature, that same child who was beating her chest with her little fist, and raise your edifice on the foundation of her unrequited tears—would you agree to be the architect on such conditions?

Key Principle

We Cannot Accept God’s Existence

We Cannot Accept God’s Existence

-

The Suffering Argument Outlined

-

A Video Explanation

Ivan argues that unnecessary suffering is not justified by a rewarding afterlife; therefore, he chooses not to accept God or the world God created. He rejects the system imposed on him, stating that no future benefit can justify current suffering, especially the immense suffering experienced by children. For Ivan, a future reward ignores and does not erode past horrors and injustice. His argument is broken down below.

(1) Truth should be pursued without harm to its searchers.

Example: Truth is an inherent good. Requiring harm on an individual to reach truth taints that goodness, as it becomes attached to suffering. For example, when President Harry Truman decided to drop the nuclear bombs on Japan, it was in pursuit of peace, a noble goal. However, the means by which he achieved that peace required immense suffering. This taints the goodness of that peace, as reflected by the way history has treated Truman’s decision.

(2) God has crafted a world that requires suffering for one to reach truth.

Example: Many religions rationalize suffering and evil as necessary parts of the world, almost as a test to determine whether one will enter Heaven.

(3) Suffering causes immense harm on individuals that is often unnecessary and cruel.

Example: Any of the four stories above describe scenarios where children were subjected to cruel and unnecessary suffering.

(4) A future reward does not justify current suffering, as that suffering taints the reward.

Example: Consider the family of a murder victim who watch the murderer get sentenced to jail in court. They might feel some form of closure watching the criminal be brought to justice, but it does not change the fact that a family member has died. No matter what happens, the murderer’s sentence will always be a reminder of the suffering that occurred to bring about that sentence.

(C) We cannot accept God’s world or His existence.

Feel free to watch this Crash Course video further exploring the Problem of Evil and potential responses.

Objection

Responses to the Problem of Evil

Responses to the Problem of Evil

-

Aquinas and the Test of Evil

-

The Free Will Defense

-

Freedom as Responsibility

In St. Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae I.49, the Doctor of the Church proposes a theistic defense of God by responding to the Problem of Evil. Since the focus of this interactive essay is Dostoyevsky’s argument, we won’t delve too deep into Aquinas. Instead, we’ll go over a brief summary of Aquinas’s argument in defense of believing in the existence of God.

For Aquinas, there is a distinction between natural evil and moral evil. Natural evil refers to events of suffering in the world not caused by human intervention, such as natural disasters. Aquinas believes that this natural evil is sometimes necessary to maintain order in the universe, which God uses to ensure a just balance. The issue comes when humans attempt to apply their moral standards to an omniscient, omnipotent being. It is impossible to understand God’s goodness because it defies any standard of good we can create, no matter how pure or intellectual. Thus, there is no true way to understand why God permits evil.

Moral evil is the result of an individual intentionally doing something or failing to do something that prevents one from realizing their full potential. When commenting on the Book of Job, Aquinas suggests that the suffering one experiences in this world can be justified by the joys of the afterlife. Evil is necessary to test the goodness of individuals, and those people are rewarded with a blissful afterlife. The eternity of this afterlife versus the relatively short-term suffering in a human’s life justifies the existence of evil if it is viewed as a test.

This video explores the free will argument in favor of God’s existence. It argues that free will is an essential aspect of human existence that necessitates the existence of evil. If evil did not exist, we would not have the ability to perform immoral actions, which then prevents us from understanding the importance of morality or making good choices in the first place. Free will enables us to understand and appreciate these concepts, enjoying our full potential as human beings.

Taking the free will defense one step further, a third response is that freedom bestows a responsibility upon humans to assist God in limiting the evil in the world. God created humans as his stewards of creation, and free will provides humans the opportunity to partake in a partnership with God to protect all of creation. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks explains this argument in the video below.

Acknowledgments

This digital essay was prepared by GGL Fellow Blake Ziegler.