Friedrich Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Modern Morality

Full Text and Selected Passages

Most of the readings for this lecture are from Friedrich Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality. You can access the full text here. The selected passages for this digital essay can be found here.

Who was Friedrich Nietzsche?

Who was Friedrich Nietzsche?

-

Why Was He Writing?

-

Wasn’t He a Nazi?

The New Socrates?

Friedrich Nietzsche (Nee’-Cha) was born in 1844 in Germany. It might be helpful to think of him as following in the footsteps of Socrates. Like Socrates, Nietzsche engages in dialogue in order to make us question our conventional ways of understanding truth, morality, and the world around us. He challenges what he sees as the great errors of the modern age: the perception that technology and science are limitless, the belief in objective morality, and the ideals of nationalism. And also like Socrates, he gives lots of criticisms but few clear answers! This is partially because both philosophers start from a humble standpoint: Socrates admits that “All he knows is that he knows nothing,” and Nietzsche reminds us that we are all animals approaching any problem from a certain biased perspective. Just like John Stuart Mill, Nietzsche is a proponent of Epistemic Relativism, the position that knowledge is valid only relatively to a specific context, society, culture or individual.

Conflict Breeds Creation

Alas! What are you, after all, my written and painted thoughts!… You have already doffed your novelty, and some of you, I fear, are ready to become truths, so immortal do they look, so pathetically honest, so tedious! And was it ever otherwise? (Beyond Good & Evil, section 296)

Nietzsche is part philosopher, part psychologist, part comparative linguist, and part historian, but above all he is an artist. He does not present his work as the Truth, nor does he want you to throw away your uncritical beliefs and uncritically accept his. Rather he wants to present you with an alternative picture of life — a new perspective — and he wants you to put your beliefs in strife with this new picture. This is why you will often see him using flagrant and hyperbolic language uncharacteristic of other philosophers. He does this to immediately force you, the reader, into a defensive position, where you must think critically in order to defend your beliefs or abandon them. His exaggerated and often cryptic language forces you to think for yourself, rather than blindly follow him.

Late in his life, Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown, and was transferred to the care of his sister, Elizabeth Förster-Nietzsche, despite Nietzsche’s many falling outs with her. Elizabeth, along with her husband Bernhard Förster, were virulently anti-Semitic. So much so, in fact, that they even eventually founded a Utopian “Aryan” colony in the Paraguayan jungle called Nueva Germania in 1887 (needless to say, it did not last long. Bernhard committed suicide in 2 years and Elizabeth returned to Germany in 6).

Once Nietzsche was placed in their care, they began doctoring his works and publishing them to take advantage of his popularity in order to further their Aryan-supremacist agenda. They added passages of their own writing, removed Nietzsche’s passages that were explicitly against anti-Semitism, and otherwise changed passages to align his philosophy with theirs. Elizabeth even falsified letters he wrote later in life. Of the collection of 505 of her brother’s letters that Förster-Nietzsche published in 1909, just 60 were the original versions and 32 of them were entirely made up (source).

This tragic misrepresentation of Nietzsche’s philosophy has stained his legacy. Hitler and the Nazi party selectively read Nietzsche’s works in order to bolster their regime, and white supremacists today do much the same thing. So read his works carefully, and be weary of media portrayals of Nietzsche.

“It must be taken into the bargain, if various clouds and disturbances – in short, slight attacks of stupidity – pass over the spirit of a people that suffers and WANTS to suffer from national nervous fever and political ambition: for instance, among present-day Germans there is alternately the anti-French folly, the anti-Semitic folly, the anti-Polish folly…” (Beyond Good & Evil, section 251)

“This most anti-cultural sickness and unreason there is, nationalism, this nervose nationale with which Europe is sick, this perpetuation of European particularism, of petty politics…is a dead-end street.” (Ecce Homo)

“Since then I’ve had difficulty coming up with any of the tenderness and protectiveness I’ve so long felt toward you. The separation between us is thereby decided in really the most absurd way. Have you grasped nothing of the reason why I am in the world?…Now it has gone so far that I have to defend myself hand and foot against people who confuse me with these anti-Semitic canaille; after my own sister, my former sister, and after Widemann more recently have given the impetus to this most dire of all confusions. After I read the name Zarathustra in the anti-Semitic Correspondence my forbearance came to an end. I am now in a position of emergency defense against your spouse’s Party. These accursed anti-Semite deformities shall not sully my ideal!!” (draft of a letter from Nietzsche to his sister)

Key Principle

What is a Genealogy?

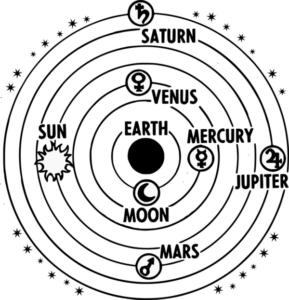

We are reading selections from Nietzsche’s On The Genealogy of Morals and Beyond Good and Evil. In these works, he gives a “genealogy” of our modern conception of morality, which he believes is dominated by Christianity. So what exactly does a “genealogy” of a concept such as morality look like?

Conventional histories and philosophical texts often trace many disparate facets of modern life back to one single event or fundamental principle or trace the linear evolution of a concept over time. For example, a historian might look at the crucifixion of Jesus, and trace its many impacts on political, social, and economic life throughout history. Or a linguist might look at when the word “good” first became used and trace the meaning of this single word in isolation up to the modern use of the word “good”.

A genealogy, on the other hand, shows how a single modern concept has its roots far back in the past in many disparate events and ideas, much like a family tree shows how one person today is the product of many disparate ancestors. Rather than giving arguments in premise-conclusion form, a genealogy tells a story of how a concept, such as the Christian moral worldview, came to be. Nietzsche urges philosophers to acknowledge a crucial fact about ideas: they are historically rooted. Ideas like Christian morality, or the Enlightenment, or Social Darwinism, do not develop in isolation from their historical, political, social, and economic context. Quite the opposite – they arise largely as a result of this context. The ideas of the Enlightenment – self-determination and individual freedom, emphasis on science over faith, democracy over absolutism, etc – evolved as a result of the Age of Exploration, the invention of the printing press, and the growth of capitalism. In the same way, Nietzsche claims that modern morality evolved from distinct historical trends and psychological phenomena.

Most importantly, a genealogy is descriptive – it describes a narrative arc without saying that this development is right or wrong, good or bad. Nevertheless, if Nietzsche can show you that a concept like your moral worldview does not actually come from where you think it does, and in fact has a rather unflattering history, this might be cause to question why you believe in it. Hence, Nietzsche — like Socrates — can be interpreted as engaging in a kind of skeptical project.

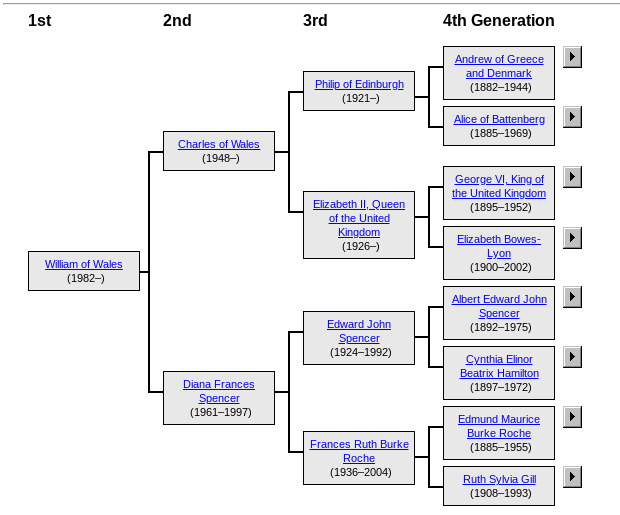

Genealogy of Prince William

The most common form of genealogy is a family tree, starting from distant ancestors and moving forward through generations to grandparents, parents, and ultimately to a single person.

Genealogy of Rock and Roll

Genealogies can also be given to concepts. This genealogy — courtesy of the timeless classic movie School of Rock — traces the changes in Rock & Roll over time and how these changes influenced each other.

Thought Experiment

Genealogy of Morality: Book 2, Section 16

At this point I can no longer avoid giving a first, preliminary expression to my own theory on the origin of ‘bad conscience’: it is not easy to get a hearing for this hypothesis and it needs to be pondered, watched and slept on. I look on bad conscience as a serious illness to which man was forced to succumb by the pressure of the most fundamental of all changes which he experienced, – that change whereby he finally found himself imprisoned within the confines of society and peace. It must have been no different for these semi-animals, happily adapted to the wilderness, war, the wandering life and adventure than it was for the sea animals when they were forced to either become land animals or perish – at one go, all instincts were devalued and ‘suspended’. Now they had to walk on their feet and ‘carry themselves’, whereas they had been carried by the water up till then: a terrible heaviness bore down on them. They felt they were clumsy at performing the simplest task, they did not have their familiar guide any more for this new, unknown world, those regulating impulses that unconsciously led them to safety – the poor things were reduced to relying on thinking, inference, calculation, and the connecting of cause with effect, that is, to relying on their ‘consciousness’, that most impoverished and error-prone organ! I do not think there has ever been such a feeling of misery on earth, such a leaden discomfort, – and meanwhile, the old instincts had not suddenly ceased to make their demands! But it was difficult and seldom possible to give in to them: they mainly had to seek new and as it were underground gratifications. All instincts which are not discharged outwardly turn inwards – this is what I call the internalization of man: with it there now evolves in man what will later be called his ‘soul’. The whole inner world, originally stretched thinly as though between two layers of skin, was expanded and extended itself and gained depth, breadth and height in proportion to the degree that the external discharge of man’s instincts was obstructed. Those terrible bulwarks with which state organizations protected themselves against the old instincts of freedom – punishments are a primary instance of this kind of bulwark – had the result that all those instincts of the wild, free, roving man were turned backwards, against man himself. Animosity, cruelty, the pleasure of pursuing, raiding, changing and destroying – all this was pitted against the person who had such instincts: that is the origin of ‘bad conscience’. Lacking external enemies and obstacles, and forced into the oppressive narrowness and conformity of custom, man impatiently ripped himself apart, persecuted himself, gnawed at himself, gave himself no peace and abused himself, this animal who battered himself raw on the bars of his cage and who is supposed to be ‘tamed’; man, full of emptiness and torn apart with homesickness for the desert, has had to create from within himself an adventure, a torture-chamber, an unsafe and hazardous wilderness – this fool, this prisoner consumed with longing and despair, became the inventor of ‘bad conscience’. With it, however, the worst and most insidious illness was introduced, one from which mankind has not yet recovered; man’s sickness of man, of himself: as the result of a forcible breach with his animal past, a simultaneous leap and fall into new situations and conditions of existence, a declaration of war against all the old instincts on which, up till then, his strength, pleasure and formidableness had been based. Let us immediately add that, on the other hand, the prospect of an animal soul turning against itself, taking a part against itself, was something so new, profound, unheard-of, puzzling contradictory and momentous on earth that the whole character of the world changed in an essential way. Indeed, a divine audience was needed to appreciate the spectacle that began then, but the end of which is not yet in sight, – a spectacle too subtle, too wonderful, too paradoxical to be allowed to be played senselessly unobserved on some ridiculous planet! Since that time, man has been included among the most unexpected and exciting throws of dice played by Heraclitus’ ‘great child’, call him Zeus or fate – he arouses interest, tension, hope, almost certainty for himself, as though something were being announced through him, were being prepared, as though man were not an end but just a path, an episode, a bridge, a great promise . . .

Key Principle

Bad Conscience

Bad Conscience

-

The Genealogical Picture

-

Social Responsibility

-

The Internalization of Man

-

Bad Conscience

Here we see a portion of Nietzsche’s genealogy of morality, culminating in one of his key concepts: the bad conscience. We’ll look at the details supporting each of these boxes in the following tabs

The relationship of a debtor to his creditor in civil law, about which I have written at length already, was for a second time transformed through interpretation, in a historically extremely strange and curious manner, into… the relationship of the present generation to their forebears. Within the original tribal association… the living generation always acknowledged a legal obligation towards the earlier generation, and in particular towards the earliest, which founded the tribe. There is a prevailing conviction that the tribe exists only because of the sacrifices and deeds of the forefathers, and that these have to be paid back with sacrifices and deeds: people recognize an indebtedness… What can people give them in return? Sacrifices, feasts, chapels, tributes, above all, obedience – for all traditions are, as works of the ancestors, also their rules and orders. Do people ever give them enough? This suspicion remains and grows: from time to time it exacts a payment on a grand scale – the infamous sacrifice of the first-born, for example… (Genealogy 2:19)

Nietzsche claims that in society there exists ‘creditor-debtor’ social relationships, in which one person (the debtor), for whatever reason, owes something to another person (the creditor). There also exists, in virtually every society, a tendency to honor and remember their ancestors, especially the founders of the society, and to tell stories in praise of their feats and abilities. These two concepts combined to form the idea of ancestors and founders as creditors and descendants as debtors. He says people feel they owe a debt to the people who came before them, and this is repaid through various feasts, monuments, and above all obedience to tradition and laws.

For example, consider America’s relationship to its own founders. Is it not true that Americans feel indebted to them, seek to carry on their traditions, and build monuments honoring them? We even refer to them as our “Fathers”. This is similar to Nietzsche’s point here.

All instincts which are not discharged outwardly turn inwards – this is what I call the internalization of man: with it there now evolves in man what will later be called his ‘soul’. The whole inner world, originally stretched thinly as though between two layers of skin, was expanded and extended itself and gained depth, breadth and height in proportion to the degree that the external discharge of man’s instincts was obstructed. (Genealogy 2:16)

Nietzsche is making a claim here about the fundamental psychology of a human being. He claims that when our urges, instincts, and desires are thwarted – say, if we lack the courage to carry them out or the object of our desires can’t be found – they don’t just dissipate. Rather, they turn inward and inflict harm on our psyche. This is the basic process of self-reflection at work, and it causes this psyche, or inner realm, to grow in the size and strength. Eventually, it becomes so big that people think of it as its own entity, separate from the body, which they call the “soul.”

Modern psychologists have called this inner realm Nietzsche is describing by many names, such as “consciousness,” your “conscience,” and the “self.” Most notably, Sigmund Freud describes this repression of instincts and desires, or the “id,” as the origin of the “ego” and the “superego.” Like Nietzsche, he also claims that the failure or prevention of the satiation of desires and instincts causes harm to the psyche, and makes us do all sorts of things to rationalize and ignore our urges, things which he calls “defense mechanisms.” In fact, many aspects of Freud’s theories are prefigured in Nietzsche. Freud, who did the bulk of his writing shortly after Nietzsche, insists that he never read Nietzsche’s works.

I look on bad conscience as a serious illness to which man was forced to succumb by the pressure of the most fundamental of all changes which he experienced – that change whereby he finally found himself imprisoned within the confines of society and peace (Genealogy 2:16)

It is not easy to get a hearing for this hypothesis and it needs to be pondered, watched, and slept on. (Genealogy 2:16)

This passage is at once beautiful, horrifying, and hard to understand. So let’s break it down: Bad conscience is the internalization of man that happens when people form a society. In order to form a peaceful society, people must curtail some of their basic instincts in exchange for safety, community, and mutual assistance. No more taking whatever you want, mating whenever you can, or flinging feces around like our primate cousins – we live in a society now, with rules and painful consequences for breaking those rules. Our instincts are further curtailed by our feeling of indebtedness to the founding ancestors of our society, and the need we feel to carry on their customs and repay our debts to them. But our brains are not adapted to live in this world of office buildings and traffic lines; we still have the instincts and desires from our days wandering the African plains. And as society curtails more of these instincts, the inner realm grows in size and intensity, creating ever more disdain for oneself and one’s natural urges. Bad conscience is precisely this internalized self-hatred caused by the entrance of people into a society which blocks them from expressing all of their instincts and desires.

Thought Experiment

Genealogy of Morality: Book 1, Section 10

The beginning of the slaves’ revolt in morality occurs when ressentiment itself turns creative and gives birth to values: the ressentiment of those beings who, denied the proper response of action, compensate for it only with imaginary revenge. Whereas all noble morality grows out of a triumphant saying ‘yes’ to itself, slave morality says ‘no’ on principle to everything that is ‘outside’, ‘other’, ‘non-self’: and this ‘no’ is its creative deed. This reversal of the evaluating glance – this essential orientation to the outside instead of back onto itself – is a feature of ressentiment: in order to come about, slave morality first has to have an opposing, external world, it needs, physiologically speaking, external stimuli in order to act at all, – its action is basically a reaction. The opposite is the case with the noble method of valuation: this acts and grows spontaneously, seeking out its opposite only so that it can say ‘yes’ to itself even more thankfully and exultantly, – its negative concept ‘low’, ‘common’, ‘bad’ is only a pale contrast created after the event compared to its positive basic concept, saturated with life and passion, ‘we the noble, the good, the beautiful and the happy!’ When the noble method of valuation makes a mistake and sins against reality, this happens in relation to the sphere with which it is not sufficiently familiar, a true knowledge of which, indeed, it rigidly resists: in some circumstances, it misjudges the sphere it despises, that of the common man, the rabble; on the other hand, we should bear in mind that the distortion which results from the feeling of contempt, disdain and superciliousness, always assuming that the image of the despised person is distorted, remains far behind the distortion with which the entrenched hatred and revenge of the powerless man attacks his opponent – in effigy of course. Indeed, contempt has too much negligence, nonchalance, complacency and impatience, even too much personal cheerfulness mixed into it, for it to be in a position to transform its object into a real caricature and monster. Nor should one fail to hear the almost kindly nuances which the Greek nobility, for example, places in all words that it uses to distinguish itself from the rabble; a sort of sympathy, consideration and indulgence incessantly permeates and sugars them, with the result that nearly all words referring to the common man remain as expressions for ‘unhappy’, ‘pitiable’ (compare δειλός, δειλαιος, πονηρός, μοχθηρός, the last two actually designating the common man as slave worker and beast of burden) – and on the other hand, ‘bad’, ‘low’ and ‘unhappy’ have never ceased to reverberate in the Greek ear in a tone in which ‘unhappy’ predominates: this is a legacy of the old, nobler, aristocratic method of valuation that does not deny itself even in contempt (– philologists will remember the sense in which οιζυρος, ανολβος, τλήμων, δυστυχείν, ξυμΦορά are used). The ‘well-born’ felt they were ‘the happy’; they did not need first of all to construct their happiness artificially by looking at their enemies, or in some cases by talking themselves into it, lying themselves into it (as all men of ressentiment are wont to do); and also, as complete men bursting with strength and therefore necessarily active, they knew they must not separate happiness from action, – being active is by necessity counted as part of happiness (this is the etymological derivation of ενπράττειν) – all very much the opposite of ‘happiness’ at the level of the powerless, the oppressed, and those rankled with poisonous and hostile feelings, for whom it manifests itself as essentially a narcotic, an anaesthetic, rest, peace, ‘sabbath’, relaxation of the mind and stretching of the limbs, in short as something passive. While the noble man is confident and frank with himself (ϒενναίος, ‘of noble birth’, underlines the nuance ‘upright’ and probably ‘naïve’ as well), the man of ressentiment is neither upright nor naïve, nor honest and straight with himself. His soul squints; his mind loves dark corners, secret paths and back-doors, everything secretive appeals to him as being his world, his security, his comfort; he knows all about keeping quiet, not forgetting, waiting, temporarily humbling and abasing himself. A race of such men of ressentiment will inevitably end up cleverer than any noble race, and will respect cleverness to a quite different degree as well: namely, as a condition of existence of the first rank, whilst the cleverness of noble men can easily have a subtle aftertaste of luxury and refinement about it: – precisely because in this area, it is nowhere near as important as the complete certainty of function of the governing unconscious instincts, nor indeed as important as a certain lack of cleverness, such as a daring charge at danger or at the enemy, or those frenzied sudden fits of anger, love, reverence, gratitude and revenge by which noble souls down the ages have recognized one another. When ressentiment does occur in the noble man himself, it is consumed and exhausted in an immediate reaction, and therefore it does not poison, on the other hand, it does not occur at all in countless cases where it is unavoidable for all who are weak and powerless. To be unable to take his enemies, his misfortunes and even his misdeeds seriously for long – that is the sign of strong, rounded natures with a superabundance of a power which is flexible, formative, healing and can make one forget (a good example from the modern world is Mirabeau, who had no recall for the insults and slights directed at him and who could not forgive, simply because he – forgot.) A man like this shakes from him, with one shrug, many worms which would have burrowed into another man; actual ‘love of your enemies’ is also possible here and here alone – assuming it is possible at all on earth. How much respect a noble man has for his enemies! – and a respect of that sort is a bridge to love . . . For he insists on having his enemy to himself, as a mark of distinction, indeed he will tolerate as enemies none other than such as have nothing to be despised and a great deal to be honoured! Against this, imagine ‘the enemy’ as conceived of by the man of ressentiment – and here we have his deed, his creation: he has conceived of the ‘evil enemy’, ‘the evil one’ as a basic idea to which he now thinks up a copy and counterpart, the ‘good one’ – himself!

Key Principle

The Origin of ‘Good’ and ‘Evil’

The Origin of Good and Evil

-

The Genealogical Picture

-

Will to Power

-

Nobles, Ignobles, and Ressentiment

-

Good and Evil

Here is another piece of Nietzsche’s genealogy, starting from his concept of the “Will to Power” and ending with the distinction between ‘good’ and ‘evil’. Learn more in the following tabs.

That imperious something which is popularly called “the spirit,” wishes to be master internally and externally, and to feel itself master… [It is] a binding, taming, imperious, and essentially ruling will. It’s requirements and capacities here, are the same as those assigned by physiologists to everything that lives, grows, and multiplies. The power of the spirit to appropriate foreign elements reveals itself in a strong tendency to assimilate the new to the old, to simplify the manifold, to overlook or repudiate the absolutely contradictory; just as it arbitrarily re-underlines, makes prominent, and falsifies for itself certain traits and lines in the foreign elements, in every portion of the “outside world.” Its object thereby is the incorporation of new “experiences,” the assortment of new things in the old arrangements – in short, growth; or more properly, the FEELING of growth, the feeling of increased power – is its object. (Beyond Good and Evil section 230)

The Will to Power is perhaps Nietzsche’s most quoted and most misunderstood concept. Nietzsche is claiming here that the fundamental drive for all living things is the urge to obtain and exercise power. Nietzsche is not thinking of power purely in the sense of physical, political, or economic domination, although those are forms the Will to Power can take. A plant taking in energy from the sun and incorporating it into itself is also a form of power, or a lion consuming a zebra. Even a scholar gaining knowledge about a particular object, time, or phenomenon is a way of exerting power over that thing. Anything that makes you feel like you are master over something can be the object of your Will to Power.

In practice, this will builds up a system of knowing and interacting with the world, and as you experience new things, your Will to Power incorporates these new things into your already constructed system. This is why the Will to Power is sometimes self-deceiving – it highlights or ignores certain aspects of the world in order to fit it into your preconceived system and maintain your feeling of superiority. Think of psychological concepts like cognitive dissonance, confirmation bias, and echo chambers. What do you do when reality does not mesh with your prior notions? Do you reinterpret reality or rethink your notions about reality?

In sections 4-11 of part 1 of Nietzsche’s Genealogy, Nietzsche claims that there are two fundamental tendencies of humans, the noble and the ignoble. Of course, both tendencies exist in all modern people in varying degrees. But to present a more simplified narrative, Nietzsche creates a thought experiment, similar to social contract theorists like Glaucon or Thomas Hobbes or John Locke. He imagines a hypothetical distant past where the two tendencies existed separately in a purely noble class of people and an purely ignoble class. The Will to Power existed in both classes, but it manifested itself in different ways.

The Nobles had a “superabundance” of natural power so that whatever they desired they could obtain (Their will to power was never thwarted, and thus they never had to self-reflect, or reinterpret the world in self-deceiving terms). Consequently, they acted without pre-meditation, they gave little thought to slights against them, and they lived a life of luxury, activity, self-absorption, and blissful ignorance. Whatever they did, they described as ‘good,’ and whomever could not do what they did were simply lacking, or ‘bad.’ These were not moral terms, but merely descriptions of reality.

The Ignoble, on the other hand, are both oppressed and constitutionally weaker than the Nobles, and their Will to Power is blocked at every turn by these oppressors and by weakness. Consequently, they are unable to spontaneously see themselves or their lives in any positive way, as intrinsically “good,” like the Nobles can. The Ignoble develop a reactive and negative sentiment towards the oppressive Nobles which Nietzsche calls ressentiment. (Pronounced: Ray-zant-ay-mant). Because the Ignobles’ Will to Power is thwarted at first, the Ignoble are driven to self-reflect, and reimagine the world in a way that makes them feel like they are masters. The form this re-imagination will take is the invention of a new form of valuation: ‘evil’.

One should ask who is actually evil in the sense of the morality of ressentiment. The stern reply is: precisely the ‘good’ person of the other morality, the noble, powerful, dominating one, but re-touched, re interpreted and reviewed through the poisonous eye of ressentiment. (Genealogy 11)

This is perhaps the most pivotal moment in the history of Western thought for Nietzsche. The Ignoble, finding their Will to Power thwarted at every turn by their own weakness or the oppression of the Nobles, whom they resent deeply for their freedom to exert their Will however they please, re-imagine the world in a way that makes them the masters. To do this, they look at the Noble way of life and say “No, we would not choose to be that way. That way is evil.” In doing this, they make themselves and the Nobles into conscious, freely choosing subjects who are responsible for what effects they choose to cause. Thus, the Ignoble create a whole new system of values, this time not merely descriptive but “normative,” in that the Noble way of life is a choice the Nobles made, not their nature, and their choice is the wrong one. By contrast, the Ignoble way of life is moral and “good.” Confidence becomes vanity, taking what you want becomes greed and gluttony, leisure becomes sloth, being passionate becomes wrath. By contrast, not getting what you want becomes temperance, being unattractive becomes chastity, having to work all day becomes diligence, not taking revenge becomes composure, etc. etc.

Characteristics of the Ignoble People (which become their values: Modest, Kind, Help Fellow Sufferers, Patient, Obedient, Pitying, Egalitarian, Resent Powerful.

Characteristics of the Noble People (which become their values): Brave, Confident, Reckless, Vain or Egocentric, Seek Vigorous Activities and Competition.

Argument

Guilt, Sin, and Modern Morality

Guilt, Sin, and Modern Morality

-

The Genealogical Picture

-

Modern Morality

-

Christianity and the Secular World

-

So what should we do?

Here is a more complete picture of Nietzsche’s genealogy, combining the two previous sections we learned about and culminating in the birth of modern morality.

The Emergence of the Priests

In sections 6 and 7 of part 1, Nietzsche describes a split in the noble class between what he calls the “warriors” and “priests.” The warriors base their conception of superiority (what separates them from the Ignoble) on physical power, and thus desire things to maintain this vigor, such as war, adventure, dancing, and “everything else that contains strong, free, happy action.” The priests base their superiority on an obsession with purity, and thus desire cleanliness, reservation, safety, and all things that prevent the soiling of their purity.

Guilt and Sin

The main contrivance which the ascetic priest allowed himself to use in order to make the human soul resound with every kind of heartrending and ecstatic music was – as everyone knows – his utilization of the feeling of guilt. The previous essay indicated the descent of this feeling briefly – as a piece of animal-psychology, no more: there we encountered the feeling of guilt in its raw state, as it were. Only in the hands of the priest, this real artist in feelings of guilt, did it take shape – and what a shape! ‘Sin’ – for that is the name for the priestly reinterpretation of the animal ‘bad conscience’ (cruelty turned back on itself) – has been the greatest event in the history of the sick soul up till now: with sin, we have the most dangerous and disastrous trick of religious interpretation. Man, suffering from himself in some way, at all events physiologically, rather like an animal imprisoned in a cage, unclear as to why? what for? and yearning for reasons – reasons bring relief –, yearning for cures and narcotics as well, finally consults someone who knows hidden things too – and lo and behold! from this magician, the ascetic priest, he receives the first tip as to the ‘cause’ of his suffering: he should look for it within himself, in guilt, in a piece of the past, he should understand his suffering itself as a condition of punishment. (Genealogy 3:20)

What do you get when you combine bad conscience, Ignoble morality, and the priestly class? For Nietzsche, SIN. The priests, obsessed with self-purification, buy into the moralizing system of the Ignoble, in which actions are not merely the results of nature but the effects of subjects who made a conscious choice to be as they are. The Ignoble, now convinced that they are “good,” yet still suffering because they cannot fully express their instincts, desires, and Will to Power, long for release or at least justification for their suffering. The priests give this to them by telling them they suffer not simply because their desires were unfulfilled or their Will did not conquer its object, but because they desired wrongly, they exercised their will wrongly, and they are being punished for it. The priests redirect ressentiment, previously directed outward at the Nobles, to inward at the Ignoble themselves: it is your fault that you suffer. Your suffering is punishment for your wrongdoing, your sins. And who could possibly have the power to set and enforce objective standards of right and wrongdoing? God. God, the primeval ancestor, is created as an omnipotent, judgemental being who punishes the sinners and rewards the pure.

Christianity

Is Nietzsche wrong about human nature, about the fundamentals of reality, about the history of Western thought? If you think he is, then he pressures you to describe an alternative genealogy. Tell us where Christianity really came from, explain history in a different way, and give an alternative account of human nature that does not include repressed instincts or the Will to Power. Genealogical arguments succeed only when the genealogies they provide are the best explanation of some principle and demonstrate that the principle need not be true to seem true to us.The enduring question for Nietzsche is whether his genealogy is the best explanation for religious belief. So we must ask where history and biology support his claims, and where his speculations were off.

Remember that even for a Nietzschean, just because Christianity has this history does not necessarily mean it is wrong to follow it, provided that you are honest with yourself about what it is and what it does for you. In fact, Nietzsche was in some ways quite fond of Jesus Christ. On Nietzsche’s interpretation, Jesus was a radical, mobilizing the masses against the noble priests and all their moralizing sentiments about guilt, atonement, and salvation through faith alone. Nietzsche believed that Jesus presented goodness as a way of life, somewhat like the nobles who found happiness and goodness in action. So if you identify with Nietzsche but still want to be a Christian, live like Jesus lived! Question authority! Live a life of action! Love everyone, and don’t be judgemental of others or of yourself.

The Secular World

“That which philosophers called “giving a basis to morality,”… has proved merely a learned form of good faith in prevailing morality, a new means of its expression… in its ultimate motive, a sort of denial that it is lawful for this morality to be called in question.” (Beyond Good & Evil section 186)

It might seem like Nietzsche was only describing a particular religion’s worldview, but in fact he believed all of Western society was infected with the germ of Christianity. The Ignoble morality ultimately won, and democratic nations, philosophers, scientists, and even atheists of his time were all various iterations of the same moral paradigm – a paradigm in which reason and truth are valued above everything else, instincts and passions are suppressed and scorned, and unseen, transcendental, objective morals and supernatural beings are outside of the world yet govern the world. For Nietzsche, this paradigm is the problem; Christianity is merely the progenitor. Everywhere the paradigm is given new phrasing and justification, but nowhere is the paradigm itself questioned.

“We have found that in all principal moral judgments, Europe has become unanimous, including likewise the countries where European influence prevails, in Europe people evidently know what Socrates thought he did not know, and what the famous serpent of old once promised to teach – they “know” today what is good and evil.” (Beyond Good & Evil section 202)

“Where have we to fix our hopes? In New Philosophers – there is no other alternative: in minds strong and original enough to initiate opposite estimates of value, to transvalue and invert ‘eternal valuations'” (Beyond Good & Evil section 203)

So if our whole inherited moral paradigm is wrong because it abstracts from the reality of experience, it causes us to feel guilt and to hate ourselves and our instincts, and it compels us to think we possess objective morals that can be used to judge and exclude others, what alternative way of life does Nietzsche propose?

Well, he certainly does not think the answer is a return to Noble morality and purely obeying any and all of our instincts. First of all, Nietzsche does not even think this is possible – humans have lived in society too long and are too corrupted by the Christian moral paradigm to go back to living like animals. Second, living like animals is ugly. The Ignoble’s self-reflection, self-consciousness, and self-torture, Nietzsche says, are what made the human animal beautiful and interesting! Without these tendencies, there would be no science, no religion, no philosophy, no culture, no art – all things that make human life worth living.

The problem is Ignoble morality created this rich life out of an unhealthy mindset – guilty conscience and ressentiment. So what we should strive for, then, is a rich, self-reflective life created from a more positive mindset that is not laden with all these life-denying and self-hating notions. A mindset that affirms life, that takes its guidance for action not from some external realm of gods and objectivity, but from within the world, within experience, and within the fullness of our instincts. A mindset that is above all a creator of values. Does this mean that we lose “Objective” morality? Well, yes, but Nietzsche would say we never had it to begin with! We were living under an illusory master we created ourselves, and now we have the knowledge, the experience, and the mental fortitude to turn our backs on this master. That is what Nietzsche meant when he famously declared:

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.

Want to learn more?

Here is a more in-depth, interactive version of Nietzsche’s full genealogy of Christianity. You can make the interface full-screen by clicking the arrows in the bottom right-hand corner. Use the sideways arrows in the center on the bottom to take the recommended path through the genealogy, or click on any circles to jump to info about that subject.

https://prezi.com/p/wnhzrroblsdn/genealogy-of-christianity/

The New Philospher, Creator of Values

Acknowledgments

This digital essay was prepared by GGL Fellow Sam Kennedy.