Choose Your Meaning: Jean-Paul Sartre and James Baldwin

The complete texts of the excerpts used in this essay can be found here: “Existentialism is a Humanism” by Jean-Paul Sartre and “Letter From a Region in My Mind” by James Baldwin.

Thought Experiment

Myth of Sisyphus

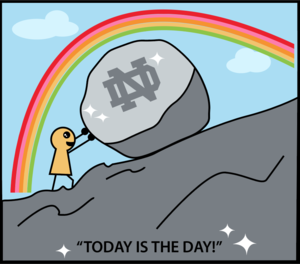

Consider the following thought experiment. You have angered the Notre Dame administrative overlords. As punishment, OCS sentences you to roll a massive boulder up a mountain. Just before you reach the top, the boulder comes crashing down to the very bottom of the mountain, and you have to start over—and over, and over, forever. And no one can help: you must perform this task in complete isolation. There is no other purpose for pushing the boulder: it doesn’t power anything or entertain anyone. From the standpoint of the universe, your task is meaningless.

Now, imagine how you, personally, would react to your situation. What would you do to cope? Maybe you’d choose to throw yourself wholeheartedly into the work. Maybe you’d persist in hoping that this time, the boulder won’t fall. Or maybe you’d just rage at the senselessness of it all.

This thought experiment originates in ancient Greek mythology, and was repopularized by the Algerian-French philosopher and novelist Albert Camus in his 1942 essay “The Myth of Sisyphus”, where he used it to examine the human condition. How do we find meaning in the face of apparent absurdity? For Camus—and for other philosophers in the existentialist tradition, which this essay will focus on—this is the central question we all must confront in life.

Key Principle

What is Existentialism?

Some philosophical schools are united by one or more common principles they believe to be true. For example, virtue ethicists believe that good actions require virtuous habits; utilitarians believe that the highest moral goal is to maximize net pleasure; and natural theologians believe that observation and reasoning can be sources of religious knowledge. But unlike these traditions, existentialism is better thought of as a characteristic attitude toward human life or style of philosophical inquiry. Here are some of its key features:

- A focus on themes such as death, anxiety, and meaning

- Challenging “common-sense” assumptions about the meaning of life

- An emphasis on authenticity in our choices about how we live our lives, and on taking responsibility for these choices.

Connection

Meet the Existentialists

Meet the Existentialists

-

Jean-Paul Sartre

-

James Baldwin

-

Together in Paris

The philosopher whose name is most closely associated with existentialism would have to be Jean-Paul Sartre. Born in Paris in 1905, Sartre’s early life was marked by personal struggles, including the death of his father when he was just two years old, and, later on, his experiences in World War II as a prisoner of war. These experiences played a significant role in shaping his philosophical ideas. His philosophical work was also closely intertwined with his lifelong personal and intellectual relationship with another prominent existentialist thinker, Simone de Bauvoir. The two met as university students at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in Paris, and became lifelong partners (though their relationship defied traditional norms of monogamous romance).

The material we will look at in this essay is from a famous lecture Sartre gave in 1946, titled “Existentialism Is a Humanism”, in which he sought to defend existentialism against criticisms and misunderstandings. He argued that existentialism does not lead to despair or nihilism but, on the contrary, highlights the importance of human freedom and choice.

James Baldwin was born in 1924 in Harlem, New York City. The grandson of a slave and the oldest of nine siblings, his early life was marked by poverty and a turbulent family life. Desperate for an escape from his situation, he found solace in books and writing, which led him to pursue a career as a writer. In 1948, when he was just 24 years old, Baldwin moved to Paris, which marked a transformative period in his life and career. He found in Paris a more racially inclusive and culturally diverse environment than what he had experienced in the United States, and it provided him with the freedom and inspiration to further develop his writing. He returned to the United States in 1957 to support the nascent Civil Rights Movement. He became a prominent voice in the struggle for racial justice, using his writing and public speeches to advocate for the dismantling of segregation.

Baldwin’s writing often dealt with complex themes such as the intersection of race, sexuality, and religion. We will look at his essay “Letter from a Region of My Mind”, first published in 1962, in which he reflects on his experiences growing up as a black man in a predominantly white society, and on the broader context of racial tensions and societal divisions in the United States.

Sartre and Baldwin most likely met each other at some point. They were both part of the lively Parisian café scene, along with other famous intellectuals, including Richard Wright, Simone de Beauvoir, and Albert Camus. The term “existentialist” became synonymous with party animal during this time due to a culture of experimentation and countercultural individualism. Still, Paris was a much lonelier place for Baldwin (an immigrant) than it was for Sartre (a local). Baldwin wasn’t a huge fan of Sartre, either, and you might understand why when we compare the two philosophies.

Argument

Sartre’s Existentialism

Sartre’s philosophy poses a fundamental challenge to how we think about our purpose in the world. In his 1946 essay “Existentialism is a Humanism,” he begins by asking: what are human beings? This question goes all the way back to ancient Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, but Sartre takes a radically different approach to it.

He begins his essay by describing what a human being is not. For instance, we are fundamentally different from a paperknife (letter opener):

If one considers an article of manufacture as, for example, a book or a paperknife – one sees that it has been made by an artisan who had a conception of it; and he has paid attention, equally, to the conception of a paper-knife and to the preexistent technique of production which is a part of that conception and is, at bottom, a formula. Thus the paper-knife is at the same time an article producible in a certain manner and one which, on the other hand, serves a definite purpose, for one cannot suppose that a man would produce a paper-knife without knowing what it was for. Let us say, then, of the paperknife that its essence – that is to say the sum of the formulae and the qualities which made its production and its definition possible – precedes its existence. The presence of such-and-such a paper-knife or book is thus determined before my eyes. Here, then, we are viewing the world from a technical standpoint, and we can say that production precedes existence.

An artisan who manufactures paperknives knows what a paperknife is and what it is used for. This means that before the artisan even creates a paperknife, or before it exists, they know its essence. Sartre concludes that for objects, essence precedes existence. But it is different with people.

What do we mean by saying that existence precedes essence? We mean that man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world – and defines himself afterwards. If man as the existentialist sees him is not definable, it is because to begin with he is nothing. He will not be anything until later, and then he will be what he makes of himself. Thus, there is no human nature, because there is no God to have a conception of it. Man simply is. Not that he is simply what he conceives himself to be, but he is what he wills, and as he conceives himself after already existing – as he wills to be after that leap towards existence. Man is nothing else but that which he makes of himself.

In many religions, God is like a superior artisan crafting humans. If this is the case, we can say God assigned us a purpose and then created us (just like the artisan does with the paperknife). But Sartre doesn’t believe there is a God. And once he takes God out of the picture, he concludes that humans come into existence without a pre-assigned purpose. The only way we can have a purpose, or an essence, is if we decide it for ourselves. To Sartre, we are more like self-aware pieces of clay without an artist that planned to use us for something. This means we must decide what to mold ourselves into.

Man is, indeed, a project which possesses a subjective life, instead of being a kind of moss, or a fungus or a cauliflower. Before that projection of the self nothing exists; not even in the heaven of intelligence: man will only attain existence when he is what he purposes to be.

So, what are human beings? We are unique because, unlike anything else, we can give ourselves our own purposes. First you exist, and only then do you determine your own essence.

Let’s see how this view of human nature compares with Aristotle’s. For Aristotle, our essence as human beings consists in our status as rational animals. This defines what we are, and determines our fundamental purpose as humans – namely, to fully actualize our rational capacities over the course of our animal lives. On this view, each of us is born into the world with an essence – with the capacities of a rational animal – and whether we live a good life or not depends on whether we live in a way that fully develops and is guided by the potential inherent in our essence (namely, by cultivating virtuous habits that guide our conduct). For Sartre, on the other hand, nobody is born with any set purpose or goal for what they are supposed to grow into. YOU get to choose your essence. So, in theory, an existentialist could reject the notion that she is supposed to be rational.

Thought Experiment

Sartre on Moral Choices

For an existentialist, how does someone know if they’re doing the right thing – if the choices they’re making are moral? Sartre answers this question with a thought experiment based on a situation one of his students once came to him for advice about.

It is World War II. You are a French youth considering joining the military in order to avenge your brother who was killed by the German offensive. You want to join the cause. The catch? Your mother, who relies on you as a source of love and support (and who recently lost her other son), would be left at home alone. If you enlist, you risk dying or losing yourself within the group identity of the military. If you stay home with your mother you help her directly, but forego the chance to be part of the greater movement. What should you do?

Sartre argues: there is no right or moral answer to the puzzle. Just as there’s no pre-destined essence for you, there’s also no choice you’re ever obliged to make. What you choose will inform your moral character, but not until you actually do the thing you decide. All that matters, in the end, is that you take responsibility for the choice you make.

Objection

Objections to Sartre’s Existentialism

- The Nihilist Threat: Meaning seems to depend on a connection to objective value. For example, having close friendships provides meaning to our lives because friendship is something valuable in its own right. If it’s up to each individual to “create their own meaning”, this connection to objective value seems to be lost. In that case, can there really be any genuine meaning in our lives? Is the kind of meaning existentialists think we “create” for ourselves really just a sham? If so, we seem to be left with an unsettling picture of our lives as ultimately meaningless, and perhaps not even worth living.

- The DIY Morality Problem: The radical freedom championed by existential thinking seems to permit each individual to make up their own moral code. But is it really plausible to think that morality is “up to us” in this way? Isn’t someone who chooses to devote themselves to serving the poor just living a better life than someone who chooses to spend every day kicking puppies and bullying children?

- Too Much Individualism: A good life seems to require a sense of belonging, and a primary source of this belonging is the shared experiences and shared sense of history that comes from belonging to various communities (your family, your university, your country, etc.). With its emphasis on individualism and nonconformity, does existentialism deprive us of these important connections?

Sartre’s Responses

We will now return to Sartre’s essay to examine how he handles these challenges.

Sartre’s Response to Objection (1)

- The existentialist finds it extremely embarrassing that God does not exist, for there disappears with Him all possibility of finding values in an intelligible heaven. It is nowhere written that “the good” exists, that one must be honest or must not lie, since we are now upon the plane where there are only men. Dostoevsky once wrote: “If God did not exist, everything would be permitted”; and that, for existentialism, is the starting point. Everything is indeed permitted if God does not exist, and man is in consequence forlorn, for he cannot find anything to depend upon either within or outside himself. He discovers forthwith, that he is without excuse. For if indeed existence precedes essence, one will never be able to explain one’s action by reference to a given and specific human nature; in other words, there is no determinism – man is free, man is freedom. Nor, on the other hand, if God does not exist, are we provided with any values or commands that could legitimise our behaviour. Thus we have neither behind us, nor before us in a luminous realm of values, any means of justification or excuse. – We are left alone, without excuse. That is what I mean when I say that man is condemned to be free. Condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty, and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.

Whether we like it or not, we are alive in a world devoid of ultimate meaning or value. In such a world, we are completely responsible for who we become. When faced with a meaningless world, we can either despair or take our lives into our own hands. Sartre urges the latter course.

Sartre’s Response to Objection (2)

- When we say that man is responsible for himself, we do not mean that he is responsible only for his own individuality, but that he is responsible for all men…If, moreover, existence precedes essence and we will to exist at the same time as we fashion our image, that image is valid for all and for the entire epoch in which we find ourselves. Our responsibility is thus much greater than we had supposed, for it concerns mankind as a whole. My action is, in consequence, a commitment on behalf of all mankind. Or if, to take a more personal case, I decide to marry and to have children, even though this decision proceeds simply from my situation, from my passion or my desire, I am thereby committing not only myself, but humanity as a whole, to the practice of monogamy.

Your responsibility for your own choices extends outwardly to those you love, and even to those you don’t know. The lives invented by each individual become models for others, so that we jointly create purpose for our lives together.

Sartre’s Response to Objection (3)

- Sartre would argue that existentialism, while emphasizing individual freedom and responsibility, does not inherently deprive individuals of the meaning that comes from identifying with a group or community. Instead, he would emphasize that individuals can create meaning through the choices they make in their interactions with others and by engaging in social and political activities that align with their values and beliefs.

The importance of creating meaning out of shared historical and social experiences finds a much stronger emphasis in the work of James Baldwin, which we will turn to now.

Black Existentialism

Philosophers in the tradition of black existentialism focus on finding meaning in life as a collective, arguing that in many cases humans are prevented from living meaningful lives as individuals. For example, black Americans are often treated by society as one homogenous group. For this reason, these philosophers think about what it really means to be free in society and challenge mainstream notions in philosophy about choice and freedom.

Argument

Baldwin on Death

Like Sartre, Baldwin also wanted to understand what it means to be human. More specifically, he was interested in the question: what does it mean to be a black person in America? In his 1963 essay “Letter From a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin reveals how he became a preacher and later decided to leave the Christian church. He considers how the meaning of black existence differs from that of white existence:

- The universe, which is not merely the stars and the moon and the planets, flowers, grass, and trees, but other people, has evolved no terms for your existence, has made no room for you, and if love will not swing wide the gates, no other power will or can. And if one despairs—as who has not?—of human love, God’s love alone is left. But God—and I felt this even then, so long ago, on that tremendous floor, unwillingly—is white. And if His love was so great, and if He loved all His children, why were we, the blacks, cast down so far? Why?

When Baldwin considers existence, he runs into a very different problem than Sartre does. Instead of asking the purpose of humanity, Baldwin must confront the privilege that comes with existence. In other words, why does there seem to be a purpose for white existence, but not black existence? Later in the essay, he explains why this question is so important:

- Therefore, whatever white people do not know about Negroes reveals, precisely and inexorably, what they do not know about themselves.

For Baldwin, the black experience in America holds the key to understanding human life. He argues that ignoring black Americans isn’t just immoral; it makes people of other racial backgrounds, but especially white people, miss out on a key aspect of the good life.

- Behind what we think of as the Russian menace lies what we do not wish to face, and what white Americans do not face when they regard a Negro: reality—the fact that life is tragic. Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.

So, what is a human being for Baldwin? A human being is someone who dies, and who knows they are going to die. Racism, which brings with it suffering and death, forces black Americans to understand this fact much more acutely.

Remember that existentialists deliberately challenge widespread assumptions about a fixed meaning of life. Baldwin claims we aren’t aiming to live the good life; we’re trying to live the tragic life. This is how Baldwin deals with the individualism objection we raised earlier. His definition of what it means to be human relies on a collective experience: death.

Doesn’t the nihilist objection especially apply to Baldwin? Who cares about life if we’re all going to die?

- It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death—ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life. One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return.

Baldwin thinks that we already know what it is like not to exist, since there was a time before we were born. We need to value this life because it rescues us from the darkness of nonexistence. Baldwin does not try to say life has no meaning or that we can make it mean something. Instead, he admits that life is a conundrum. But it is one we want to embrace.

Objection

The “Unity Problem”

In 1968, philosophy professor Paul Weiss raised an objection to Baldwin’s thinking. We will call this objection, The “Unity Problem.” In the following clip, Professor Weiss asks: why are we focusing on black versus white men? Why should we focus on race, when there are other ways of connecting men?

Notice how Weiss advocates for viewing life as an individual problem? Notice how Baldwin instantly brings up death? Baldwin responds to this objection from Weiss by pointing out that he cannot ignore his black identity: society reminds him of his blackness at every turn. So while others may be able to ignore race as a part of their existence, he simply does not have the choice. If we return to “Letter From a Region in My Mind,” however, we will see that he makes an even stronger response to this objection.

Argument

Baldwin on Love

Weiss’s objection wonders if focusing on race is arbitrary and divisive. Baldwin answers that he has no other choice but to focus on race. In his writing, he considers how race and the fact of death can actually lead to unity. It is at this point in his essay that Baldwin comes to his unique understanding of love.

“A vast amount of the energy that goes into what we call the Negro problem is produced by the white man’s profound desire not to be judged by those who are not white, not to be seen as he is, and at the same time a vast amount of the white anguish is rooted in the white man’s equally profound need to be seen as he is, to be released from the tyranny of his mirror. All of us know, whether or not we are able to admit it, that mirrors can only lie, that death by drowning is all that awaits one there. It is for this reason that love is so desperately sought and so cunningly avoided. Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within. I use the word “love” here not merely in the personal sense but as a state of being, or a state of grace—not in the infantile American sense of being made happy but in the tough and universal sense of quest and daring and growth.”

Baldwin’s optimism resides in love, which is not a fleeting feeling, but the difficult process of white people facing up to the reality of their own shame and engaging authentically with black people. There is a call for a relationship between people, not a vision of a world full of loners.

In short, we, the black and the white, deeply need each other here if we are really to become a nation—if we are really, that is, to achieve our identity, our maturity, as men and women.

By illuminating our racial identities, Baldwin isn’t being divisive. By bringing up death, Baldwin isn’t feeding nihilism. He finds that by contemplating these hard subjects, we will learn who we really are. In this sense, Baldwin recognizes there is more to being human than just knowing that we die. The only way we can understand our identity in a deeper way is by working to overcome the differences that separate us and being vulnerable with one another.

Acknowledgments

This digital essay was prepared by Mia Lecinski and Margaret McGreevy and edited by Justin Christy.