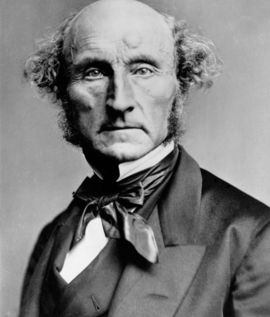

Utilitarianism: John Stuart Mill

Who is John Stuart Mill?

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was the most influential English-speaking philosopher of the nineteenth century, as well as a political economist and a prominant politician. Born in London to a family of intellectuals, Mill was educated by his father, James Mill, who was a philosopher and economist himself. He was a child prodigy, learning Greek at age three and Latin at age eight before delving into advanced philosophical works as a teenager.

Mill’s father was a close friend and follower of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, a moral theory that emphasizes the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people as the guiding principle for ethical behavior. The education he gave John Stuart Mill aimed to mold him into a utilitarian philosopher, and Mill’s most famous work, Utilitarianism (published in 1861), is a detailed explanation and defense of the theory against a range of objections. This digital essay covers Chapter 2 of that work.

As a political reformer (and Member of Parliament from 1865 to 1868), Mill advocated for economic and social policies that would promote equality and social welfare. He was a staunch advocate for women’s rights, publishing “The Subjection of Women”, a groundbreaking work that argued for equal social status between women and men. Mill was only the second Member of Parliament to advocate for women’s suffrage, and wrote in support of the abolition of slavery in the United States.

Key Principle

Utilitarianism: The Basics

Utilitarianism: The Basics

-

The Greatest Happiness Principle

-

The Importance of Sentience

-

The Felicific Calculus

Here is how Mill states the defining principle of utilitarianism:

The doctrine that the basis of morals is utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong in proportion as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By ‘happiness’ is meant pleasure and the absence of pain; by ‘unhappiness’ is meant pain and the lack of pleasure.

Let’s break this down. In this passage, Mill says that morality is all about promoting happiness (which he also calls “utility”). The more happiness an action produces, the better it is, morally speaking; and the more unhappiness an action produces, the worse it is. According to utilitarianism, then, we should strive to maximize utility in the world, producing the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people.

Mill also equates happiness with “pleasure and the absence of pain” and unhappiness with “pain and the lack of pleasure”. This view of the nature of happiness is known as hedonism.

The capacity to experience pleasure and pain is known as sentience. Human beings are sentient, and so are many animals. Utilitarians like Mill hold that the rightness or wrongness of an action depends on how the action affects all sentient beings — not just humans. In other words, in applying the Greatest Happiness Principle, we must factor in the pleasure or pain of sentient animals as well as humans.

This doesn’t mean all sentient life is completely equal. Sentience comes in degrees: different creatures — and even different individuals — can have a greater or lesser capacity to experience pain or pleasure. For example, a toad arguably cannot experience as wide a variety of pleasures and pains as a human being — such as the pleasure of humor or the pain of heartbreak — or experience them with as much intensity as humans sometimes do. Similarly, someone who is under heavy sedation has less of a capacity for pleasure and pain than you do right now (we hope!).

For utilitarians, determining the right thing to do is a matter of adding up the utility an action is likely to produce for the sentient creatures affected. For instance, suppose Jeffrey wants to go on vacation, but nobody is available to feed his cat, Whiskers. Mill would advise Jeffrey to consider whether the pleasure he would get from the vacation outweighs the pain Whiskers would experience from going without food and water.

As this illustrates, utilitarians try their best to approach moral decisions mathematically. Jeremy Bentham called this the “Felicific Calculus”.

Pleasure and the Good Life

What view of the good life does utilitarianism imply? Here’s what Mill says:

Pleasure and freedom from pain are the only things that are desirable as ends, and everything that is at all desirable is so either for the pleasure inherent in it or as means to the promotion of pleasure and the prevention of pain.

We can contrast this with Aristotle’s view that the ultimate goal of human life is eudaimonia, the state of living in accordance with one’s true nature as a rational being. For Aristotle, this involves cultivating moral and intellectual virtue in oneself. For a utilitarian like Mill, virtue is not necessarily a requirement for a good life. Anyone who is effective in promoting pleasure and preventing pain is living a good life, regardless of their personal virtue.

Which of these views do you find more plausible? Is Aristotle right in thinking that a good life requires a virtuous character? Or is pleasure ultimately the only thing that really matters, as Mill believes? When you reflect on your own goals and desires, do all of them seem to fit what Mill says above — or do you find any that seem totally unrelated to pleasure (your own or others’)?

Key Principle

Higher and Lower Pleasures

Are all pleasurable activities equal? For example, does utilitarianism imply that someone who enjoys binge-watching professional wrestling all day is spending their time just as well as someone who enjoys reading classic novels? Perhaps surprisingly, Mill doesn’t think so. In this section, Mill introduces his view that some pleasures are superior to others:

When utilitarian writers have said that mental pleasures are better than bodily ones they have mainly based this on mental pleasures being more permanent, safer, less costly and so on—i.e. from their circumstantial advantages rather than from their intrinsic nature. But they could, quite consistently with their basic principle, have taken another route: it is quite compatible with the principle of utility to recognize that some kinds of pleasure are more desirable and more valuable than others. In estimating the value of anything else, we take into account quality as well as quantity; it would be absurd if the value of pleasures were supposed to depend on quantity alone.

“What do you mean by ‘difference of quality in pleasures’? What, according to you, makes one pleasure more valuable than another, merely as a pleasure, if not its being greater in amount?” There is only one possible answer to this. Pleasure P1 is more desirable than pleasure P2 if: all or almost all people who have had experience of both give a decided preference to P1, irrespective of any feeling that they ought to prefer it. If those who are competently acquainted with both these pleasures place P1 so far above P2 that they prefer it even when they know that a greater amount of discontent will come with it, and wouldn’t give it up in exchange for any quantity of P2 that they are capable of having, we are justified in ascribing to P1 a superiority in quality that so greatly outweighs quantity as to make quantity comparatively negligible.

Consider what a virtue ethicist like Aristotle would think about this. Do you think Aristotle would agree with Mill that some pleasures are more valuable than others? If so, would their reasons be the same?

Socrates and the Fool

In the following paragraphs, Mill continues developing his doctrine of higher and lower pleasures. He explains the sense in which he thinks a life characterized by the cultivation and use of “the higher faculties” (for example, intellect and artistic sensibilities) is preferable to a life centered around “lower faculties” (such as desires for basic comforts or appetites for food and drink).

It is an unquestionable fact that the way of life that employs the higher faculties is strongly preferred to the way of life that caters only to the lower ones by people who are equally acquainted with both and equally capable of appreciating and enjoying both. Few human creatures would agree to be changed into any of the lower animals in return for a promise of the fullest allowance of animal pleasures; no intelligent human being would consent to be a fool, no educated person would prefer to be an ignoramus, no person of feeling and conscience would rather be selfish and base, even if they were convinced that the fool, the dunce or the rascal is better satisfied with his life than they are with theirs. If they ever think they would, it is only in cases of unhappiness so extreme that to escape from it they would exchange their situation for almost any other, however undesirable they may think the other to be. Someone with higher faculties requires more to make him happy, is probably capable of more acute suffering, and is certainly vulnerable to suffering at more points, than someone of an inferior type; but in spite of these drawbacks he can’t ever really wish to sink into what he feels to be a lower grade of existence.

But the most appropriate label is a sense of dignity. All human beings have this sense in one form or another, and how strongly a person has it is roughly proportional to how well endowed he is with the higher faculties. In those who have a strong sense of dignity, their dignity is so essential to their happiness that they couldn’t want, for more than a moment, anything that conflicts with it.

It is true of course that the being whose capacities of enjoyment are low has the greatest chance of having them fully satisfied and thus of being contented; and a highly endowed being will always feel that any happiness that he can look for, given how the world is, is imperfect. But he can learn to bear its imperfections, if they are at all bearable; and they won’t make him envy the person who isn’t conscious of the imperfections only because he has no sense of the good that those imperfections are imperfections of — for example, the person who isn’t bothered by the poor quality of the conducting because he doesn’t enjoy music anyway. It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool or the pig think otherwise, that is because they know only their own side of the question. The other party to the comparison knows both sides.

The utilitarian standard is not the agent’s own greatest happiness but the greatest amount of happiness altogether; and even if it can be doubted whether a noble character is always happier because of its nobleness, such a character certainly makes other people happier, and the world in general gains immensely from its existence. So utilitarianism would achieve its end only through the general cultivation of nobleness of character, even if each individual got benefit only from the nobleness of others, with his own nobleness serving to reduce his own happiness.

Self-Sacrifice

Here, Mill discusses the potential demandingness of utilitarianism in cases where personal sacrifices are required to maximize overall happiness in the world.

Only while the world is in a very imperfect state can it happen that anyone’s best chance of serving the happiness of others is through the absolute sacrifice of his own happiness; but while the world is in that imperfect state, I fully admit that the readiness to make such a sacrifice is the highest virtue that can be found in man. I would add something that may seem paradoxical: in this present imperfect condition of the world the conscious ability to do without happiness gives the best prospect of bringing about such happiness as is attainable. For nothing else can raise a person above the chances of life by making him feel that fate and fortune—let them do their worst!—have no power to subdue him. Once he feels that, it frees him from excessive anxiety about the evils of life and lets him calmly develop the sources of satisfaction that are available to him, not concerning himself with the uncertainty regarding how long they will last or the certainty that they will end.

The utilitarian morality does recognise that human beings can sacrifice their own greatest good for the good of others; it merely refuses to admit that the sacrifice is itself a good. It regards as wasted any sacrifice that doesn’t increase, or tend to increase, the sum total of happiness. The only self-renunciation it applauds is devotion to the happiness of others.

Key Principle

The Principle of Equal Consideration

Mill holds that to live a morally good life, we must be unbiased in our consideration of other beings’ happiness. Every sentient being’s pleasure or pain counts. After stating this “Principle of Equal Consideration” in the following passage, he goes on to consider how a society guided by it would be organized.

The happiness that forms the utilitarian standard of what is right in conduct is not the agent’s own happiness but that of all concerned. As between his own happiness and that of others, utilitarianism requires him to be as strictly impartial as a disinterested and benevolent spectator. In the golden rule of Jesus of Nazareth we read the complete spirit of the ethics of utility. To do as you would be done by, and to love your neighbour as yourself constitute the ideal perfection of utilitarian morality.

As the practical way to get as close as possible to this ideal, the ethics of utility would command two things. (1) First, laws and social arrangements should place the happiness (or what we may call the interest) of every individual as much as possible in harmony with the interest of the whole. (2) Education and opinion, which have such a vast power over human character, should use that power to establish in the mind of every individual an unbreakable link between his own happiness and the good of the whole; especially between his own happiness and the kinds of conduct that are conducive to universal happiness. If (2) is done properly, it will tend to have two results: (2a) The individual won’t be able to conceive the possibility of being personally happy while acting in ways opposed to the general good; and (2b) in each individual a direct impulse to promote the general good will be one of the habitual motives of action, and the feelings connected with it will fill a large and prominent place in his sentient existence. This is the true character of the utilitarian morality.

Thought Experiment

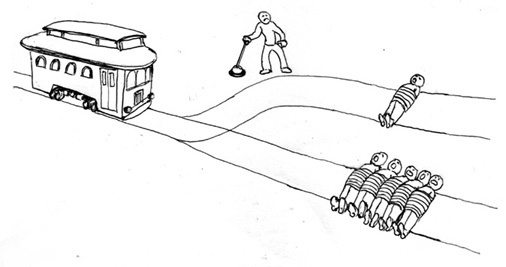

Utilitarianism in Action: The Trolley Problem

In 1967, the philosopher Philippa Foot introduced what is now one of the most famous thought experiments in ethics, known as the Trolley Problem. In the most basic version of the thought experiment, a runaway trolley is headed down a track, barreling toward five people who are tied to the track and unable to move. On a side track, there’s a single person also tied up and unable to move. You are positioned at a switch that can divert the trolley to its side track. If you do nothing, the trolley will continue on its current path and kill the five people ahead of it; if you pull the switch, you will divert the trolley onto the side track, killing the one person tied up there.

What would a utilitarian like Mill say is the right thing to do in this scenario? Would they think it matters who is tied to the tracks? Do you agree?

Objection

Objections to Utilitarianism

Objections to Utilitarianism

-

Pleasure Should Not Be the Highest Aim

-

Utilitarianism Is Burdensome

-

The Felicific Calculus Is Impractical

-

Utilitarianism Enables Hypocrisy

Mill directly addresses several objections to utilitarianism in this work. Here are some of the most important, along with Mill’s responses.

Objection: The idea that pleasure is the highest aim of human life makes us no better than base animals.

- Now, such a theory of life arouses utter dislike in many minds, including some that are among the most admirable in feeling and purpose. The view that life has (as they express it) no higher end —no better and nobler object of desire and pursuit— than pleasure they describe as utterly mean and grovelling, a doctrine worthy only of pigs.

Mill’s Response:

- The accusation implies that human beings are capable only of pleasures that pigs are also capable of. If this were true, there’d be no defence against the charge, but then it wouldn’t be a charge; for if the sources of pleasure were precisely the same for humans as for pigs, the rule of life that is good enough for them would be good enough for us. The comparison of the utilitarian life to that of beasts is felt as degrading precisely because a beast’s pleasures do not satisfy a human’s conceptions of happiness. Human beings have higher faculties than the animal appetites, and once they become conscious of them they don’t regard anything as happiness that doesn’t include their gratification.

Objection: Utilitarianism sets unrealistically high moral standards.

- Objectors sometimes find fault with utilitarianism’s standard as being too high for humanity. To require people always to act from the motive of promoting the general interests of society—that is demanding too much, they say.

Mill’s Response:

- This is to confuse the rule of action with the motive for acting. It is the business of ethics to tell us what are our duties, or by what test we can know them; but no system of ethics requires that our only motive in everything we do shall be a feeling of duty; on the contrary, ninety-nine hundredths of all our actions are done from other motives, and rightly so if the rule of duty doesn’t condemn them. It is especially unfair to utilitarianism to object to it on the basis of this particular misunderstanding, because utilitarian moralists have gone beyond almost everyone in asserting that the motive has nothing to do with the morality of the action though it has much to do with the worth of the agent. He who saves a fellow creature from drowning does what is morally right, whether his motive is duty or the hope of being paid for his trouble; he who betrays a friend who trusts him is guilty of a crime, even if his aim is to serve another friend to whom he is under greater obligations.

Objection: In practice, it is not feasible to calculate which action will maximize overall utility every time we face a decision.

- Before acting, one doesn’t have time to calculate and weigh the effects on the general happiness of any line of conduct.

Mill’s Response:

- This is just like saying: “Before acting, one doesn’t have time on each occasion to read through the Old and New Testaments; so it is impossible for us to guide our conduct by Christianity.” The answer to the objection is that there has been plenty of time, namely, the whole past duration of the human species. During all that time, mankind has been learning by experience what sorts of consequences actions are apt to have, this being something on which all the morality of life depends. The objectors talk as if the start of this course of experience had been put off until now, so that when some man feels tempted to meddle with the property or life of someone else he has to start at that moment considering for the first time whether murder and theft are harmful to human happiness!

- If mankind were agreed in considering utility to be the test of morality, they would reach agreement about what is useful, and would arrange for their notions about this to be taught to the young and enforced by law and opinion. Any ethical standard whatever can easily be “shown” to work badly if we suppose universal idiocy to be conjoined with it! But on any hypothesis short of that, mankind must by this time have acquired positive beliefs as to the effects of some actions on their happiness; and the beliefs that have thus come down to us from the experience of mankind are the rules of morality for the people in general—and for the philosopher until he succeeds in finding something better.

Objection: Utilitarianism opens the door to dishonest defenses of bad behavior.

- We are told that a utilitarian will be apt to make his own particular case an exception to moral rules; and that when he is tempted to do something wrong he will see more utility in doing it than in not doing it.

Mill’s Response:

- Is utilitarianism the only morality that can provide us with excuses for evil doing, and means of cheating our own conscience? Of course not! Such excuses are provided in abundance by all doctrines that recognise the existence of conflicting considerations as a fact in morals; and this is recognized by every doctrine that any sane person has believed. It is the fault not of any creed but of the complicated nature of human affairs that rules of conduct can’t be formulated so that they require no exceptions, and hardly any kind of action can safely be stated to be either always obligatory or always condemnable.

- Every ethical creed gives the morally responsible agent some freedom to adapt his behaviour to special features of his circumstances; and under every creed, at the opening thus made, self-deception and dishonest reasoning get in. Every moral system allows for clear cases of conflicting obligation. If utility is the basic source of moral obligations, utility can be invoked to decide between obligations whose demands are incompatible. The utility standard may be hard to apply, but it is better than having no standard. In other systems, the moral laws all claim independent authority, so that there’s no common umpire entitled to settle conflicts between them; when one of them is claimed to have precedence over another, the basis for this is little better than sophistry, allowing free scope for personal desires and preferences—unless the conflict is resolved by the unadmitted influence of considerations of utility.

Acknowledgments

This digital essay was prepared by Blake Ziegler and Justin Christy.