Learn to Live Well: Aristotle

A Brief Introduction to Aristotle

Who was Aristotle?

Aristotle (384-322 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher who learned philosophy from Plato (who in turn had learned it from Socrates). He was the tutor of Alexander the Great. Aristotle was interested in every branch of philosophy and science.

What text are these selections from?

The Nicomachean Ethics is a work consisting of ten “books” (equivalent to modern-day chapters) that lays out philosophical arguments and recommendations for students who wish to achieve happiness. It was composed around 350 BC.

Honestly, how hard is it to be happy?

Aristotle distinguishes pleasure (the feeling of gratification or enjoyment) from human flourishing or “eudaimonia’’ (the state of someone who has fulfilled their potential and is living well). Aristotle thought pleasure can be fleeting, and even individuals whose lives were going quite badly might have pleasure. Only flourishing is pursued for its own sake; it is the goal for all of our lives.

What is it for a Life to Be Good?

The Ultimate Goal of Our Lives: Happiness (I.7)

Let us again return to the good we are seeking, and ask what it can be. It seems different in different actions and arts; it is different in medicine, in strategy, and in the other arts likewise. What then is the good of each? Surely that for whose sake everything else is done. In medicine this is health, in strategy victory, in architecture a house, in any other sphere something else, and in every action and pursuit the end; for it is for the sake of this that all men do whatever else they do. Therefore, if there is an end for all that we do, this will be the good achievable by action, and if there are more than one, these will be the goods achievable by action.

Since there is evidently more than one end, and we choose some of these for the sake of something else, clearly not all ends are final ends; but the chief good is evidently something final. Therefore, if there is only one final end, this will be what we are seeking, and if there are more than one, the most final of these will be what we are seeking. Now we call that which is in itself worthy of pursuit more final than that which is worthy of pursuit for the sake of something else, and that which is never desirable for the sake of something else more final than the things that are desirable both in themselves and for the sake of that other thing, and therefore we call final without qualification that which is always desirable in itself and never for the sake of something else.

Now such a thing happiness, above all else, is held to be; for this we choose always for self and never for the sake of something else, but honor, pleasure, reason, and every virtue we choose indeed for themselves (for if nothing resulted from them we should still choose each of them), but we choose them also for the sake of happiness, judging that by means of them we shall be happy. Happiness, on the other hand, no one chooses for the sake of these, nor, in general, for anything other than itself.

Argument

The Function Argument (I.7)

The Function Argument (1.7)

-

Defining Humanity

-

The Function Argument Outlined

-

Questions about the Function Argument

Aristotle concludes Book I.7 by arguing that a defining feature of humankind — something that separates us from every other kind of thing — is our pursuit of a certain kind of happiness. Let’s carefully take apart this argument, since there is a lot of complexity in it. We’ll start with the text.

To say that happiness is the chief good seems a platitude, and a clearer account of it is still desired. This might perhaps be given, if we could first ascertain the function of man.

For just as for a flute-player, a sculptor, or an artist, and, in general, for all things that have a function or activity, the good and the “well” is thought to reside in the function, so would it seem to be for man, if he has a function. Have the carpenter, then, and the tanner certain functions or activities, and has man none? Is he born without a function? Or as eye, hand, foot, and in general each of the parts evidently has a function, may one lay it down that man similarly has a function apart from all these? What then can this be?

Life seems to be common even to plants, but we are seeking what is peculiar to man. Let us exclude, therefore, the life of nutrition and growth. Next there would be a life of perception, but it also seems to be common even to the horse, the ox, and every animal. There remains, then, an active life of the element that has a rational principle; of this, one part has such a principle in the sense of being obedient to one, the other in the sense of possessing one and exercising thought. And, as “life of the rational element” also has two meanings, we must state that life in the sense of activity is what we mean; for this seems to be the more proper sense of the term.

Now if the function of man is an activity of soul which follows or implies a rational principle, and if we say “so-and-so” and “a good so-and-so” have the same kind of function (e.g. a lyre, and a good lyre-player), with eminence in respect of goodness added, in all cases, to the name of the function (for the function of a lyre-player is to play the lyre, and that of a good lyre-player is to do so well): if this is the case, and we state the function of man to be a certain kind of life, and this to be an activity or actions of the soul implying a rational principle, and the function of a good man to be the good and noble performance of these, and if any action is well performed when it is performed in accordance with the appropriate excellence, then human good turns out to be activity of soul in accordance with virtue, and if there is more than one virtue, in accordance with the best and most complete.

But we must add “in a complete life”. For one swallow does not make a summer, nor does one day; and so too one day, or a short time, does not make a man blessed and happy.

(1) The goodness of anything is determined by whether it fulfills its function well or poorly.

For example: A good knife is one that cuts well. A poor knife can’t cut anything. A good lyre player plays beautiful music. A bad lyre player sounds… awful. Functions determine standards for goodness or badness of a thing.

(2) The function defines what that thing is.

For example: If you cannot cut anything, you are not a knife. If you cannot grow and metabolize nutrients, you are not a plant. The nature of something gives a necessary condition for being that thing.

(3) Man is defined apart from plants, animals and mere things by the fact that we can act rationally.

For example: We share biological processes of life with plants and animals. And animals have the ability to perceive–simply having a mind does not make us special. What defines humans is we can reason about goals (sometimes quite distant ones) and pursue them.

(4) A person is good to to the extent that he is good at acting rationally.

This premise follows from (1) and (3)

(5) The final, complete goal is happiness (Eudaimonia).

Aristotle is assuming this, based on the argument in the previous section.

(6) So happiness consists in doing a good job of acting rationally (aka being virtuous). [More on this in the next section].

(7) Whether a person has pursued happiness well can only be determined in the context of a complete life.

For example: You might seem to be happy if you have gotten to college. But if it turns out you use your education for to do something evil, then in fact this “achievement” hasn’t moved you closer to happiness.

(C) The goal of a human life is to rationally pursue happiness over the course of a life.

(1) The goodness of anything is determined by whether it fulfills its function well or poorly.

QUESTION: Where would these standards for good functioning come from? God? Some user manual that comes along with plants and animals?

(2) The function also defines what that thing is.

QUESTION: Can absolutely everything be defined and classified in this way? Are there any functionless things?

(3) Man is defined apart from plants, animals and mere things by the fact that we can act rationally.

QUESTION: What is rationality? What about dolphins, intelligent dogs, birds who can count? Is this what makes man special?

(4) A person is good to to the extent that he is good at acting rationally.

This premise follows from (1) and (3)

(5) The final, complete goal is happiness (Eudaimonia).

(6) So happiness consists in doing a good job of acting rationally (aka being virtuous). [More on this in the next section].

(7) Whether a person has pursued happiness well can only be determined in the context of a complete life.

QUESTION: Does this entail we cannot know if we are happy (in Aristotle’s sense) while we are still living? And what about lives that are lived well, but end on a bad note?

(C) The goal of a human life is to rationally pursue happiness over the course of a life.

Argument

The Power of Habit (II.1)

Virtue is of two kinds, intellectual and moral. Intellectual virtue generally owes its birth and its growth to teaching (for which reason it requires experience and time), while moral virtue comes about as a result of habit. From this it is plain that none of the moral virtues arises in us by nature; for nothing that exists by nature can form a habit contrary to its nature.

For instance the stone, which by nature moves downwards, cannot be habituated to move upwards, not even if one tries to train it by throwing it up ten thousand times; nor can fire be habituated to move downwards, nor can anything else that by nature behaves in one way be trained to behave in another.

Neither by nature, then, nor contrary to nature do the virtues arise in us; rather we are adapted by nature to receive them, and are made perfect by habit.

What is a virtue?

-

What is a virtue?

-

The Rest of II.1: Virtue Requires Practice

So what is Aristotle’s argument in this section? First of all, he’s making the following revolutionary (and still controversial) claim:

Virtues and vices are properties of persons (character traits) that can be acquired.

He supports this claim by arguing that:

(1) No natural properties can be changed by habituation (for example: you can’t teach a stone to fall upwards)

(2) Virtues can be changed by habituation (for example: you can teach a soldier to be more courageous)

(C) Therefore virtues cannot be natural properties

Thus, for Aristotle, we are not just naturally morally good or bad. We have some control (via learning, habituation, and the communities and groups we choose to be a part of) over whether we develop a morally good or morally bad character.

But not all of our character traits are virtues or vices. For example, outgoingness and neatness are both character traits, but neither one seems to be a virtue or a vice. So which character traits count as virtues and vices? Aristotle answers this question by defining virtues as stable personality traits that reliably dispose a person to act well, and vices as stable personality traits that reliably dispose a person to act badly.

Of all the things that come to us by nature, we first acquire the potentiality and later exhibit the activity. (This is plain in the case of the senses; for it was not by often seeing or often hearing that we got these senses: we had them before we used them, and did not come to have them by using them.) But the virtues we get by first exercising them, as also happens in the case of the arts as well. For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them, e.g. men become builders by building and lyre players by playing the lyre; so too we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts. This is confirmed by what happens in states; for legislators make the citizens good by forming habits in them, and it is in this that a good constitution differs from a bad one.

It is from the same causes and by the same means that every virtue is both produced and destroyed, and similarly every art; for it is from playing the lyre that both good and bad lyre-players are produced. For if this were not so, there would have been no need of a teacher, but all men would have been born good or bad at their craft. This, then, is the case with the virtues also: by doing the acts that we do in our dealings with other people we become just or unjust; and by doing the acts that we do in the presence of danger, and being habituated to feel fear or confidence, we become brave or cowardly. The same is true of appetites and feelings of anger: some people become temperate and good-tempered, others self-indulgent and ill-tempered, by behaving in one way or the other in the appropriate circumstances.

Thus, states of character arise out of like activities, and correspond to the differences between these. It makes no small difference, then, whether we form habits of one kind or of another from our very youth; it makes a very great difference, or rather all the difference.

Goodness Requires Practicing Good Action (II.2)

Since the present inquiry does not aim at theoretical knowledge (for we are inquiring not in order to know what virtue is, but in order that we may become good, since otherwise our inquiry would have been of no use), we must examine the nature of actions, namely how we ought to do them; for these determine also the nature of the states of character that are produced, as we have said.

But the whole account of matters of conduct must be stated in outline only and not precisely, as the accounts we demand must be in accordance with the subject-matter: matters concerned with conduct and questions of what is good for us have no fixity, any more than matters of health. The general account being of this nature, the account of particular cases is yet more lacking in exactness; for they do not fall under any art or precept but the agents themselves must in each case consider what is appropriate to the occasion, as happens also in the art of medicine or of navigation.

Key Principle

Virtue as the Mean Between Two Extremes (II.2)

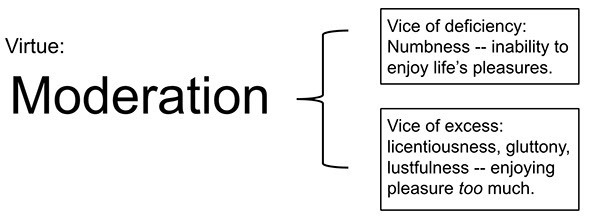

It is the nature of such things as the virtues to be destroyed by defect and excess, as we see in the case of strength and of health (for to gain light on things imperceptible we must use the evidence of sensible things): both excessive and defective exercise destroys the strength, and similarly drink or food which is above or below a certain amount destroys the health, while that which is proportionate produces, increases, and preserves it. So too is it, then, in the case of temperance and courage and the other virtues. For the person who fears everything and does not stand firm against anything becomes a coward, and the person who fears nothing at all but goes to meet every danger becomes rash; and similarly the person who indulges in every pleasure and abstains from none becomes self-indulgent, while the person who shuns every pleasure, as boors do, becomes in a way insensible. Temperance and courage, then, are destroyed by excess and defect, and preserved by the mean.

Pleasure and the Virtues (II.3)

Moral excellence is concerned with pleasures and pains: it is on account of the pleasure that we do bad things, and on account of the pain that we abstain from noble ones. Hence we ought to have been brought up from our very youth to delight in and to be pained by the things that we ought; for this is the right education.

Pleasure has been a part of our upbringing from infancy. This is why it is difficult to remove this experience, since it is so engrained in our life. And we measure our actions, some of us to a greater degree and some to a lesser, by the rule of pleasure and pain. For this reason, out whole inquiry must be about pleasure and pain; for these have no small effect on our actions being well or badly done.

Objection

Objection: How Can We Ever Become Virtuous? (II.4)

It might be asked what we mean by saying that we must become just by doing just acts, and temperate by doing temperate acts. For if people do just and temperate acts, they are already just and temperate, exactly as, if they do what is in accordance with the laws of grammar and of music, they are grammarians and musicians.

Actions are called just and temperate when they are such as the just or the temperate person would do; but it is not the one who does these that is just and temperate, but the one who also does them as just and temperate people do them. It is well said, then, that it is by doing just acts that the just person is produced, and by doing temperate acts the temperate person; without doing these no one would have even a prospect of becoming good.

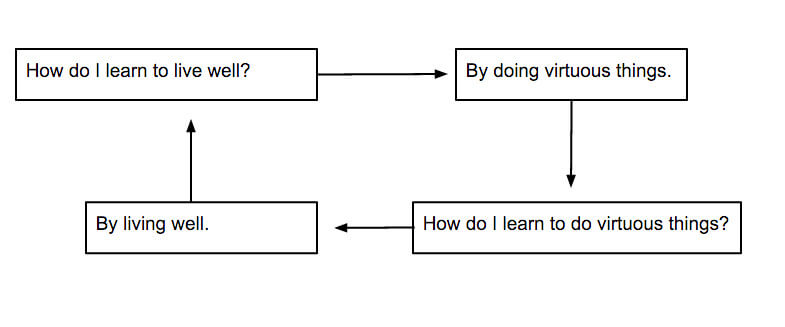

Here Aristotle considers whether his account of how we acquire virtues is circular.

Living Well is a Learned Skill (II.4)

Aristotle answers the worry by reiterating that actual practice must come before offering a theory of how to live well.

Most people do not practice acting well, but take refuge in theory and think they are being philosophers and will become good in this way, behaving somewhat like patients who listen attentively to their doctors, but do none of the things they are ordered to do. As the latter will not be made well in body by such a course of treatment, the former will not be made well in soul by such a course of philosophy.

Consider how this passage relates to our course. How does Aristotle think moral philosophy ought to be taught? Which aspects of this course do you think most closely reflect this approach? (Assignments? Lectures? Dialogue sessions? All of these working together?)

Summary & Conclusion

For Aristotle, philosophy is a deeply practical enterprise. He does not think you can live well just by reading books or studying a general theory. Instead, you need practice solving real problems and dealing with complexity. He thinks you learn virtue by developing the right kinds of habits and by having a good community around to support to you. To master the virtues, you need lots of practice and feedback. And he thinks that living well is more than just finding pleasure in your life — it is a matter of realizing your full potential as a human being, including growing in virtues like courage, moderation, and generosity.

This digital essay was prepared by Paul Blaschko, Justin Christy, and Meghan Sullivan.