Embrace the Absurd: Kierkegaard

Key Principle

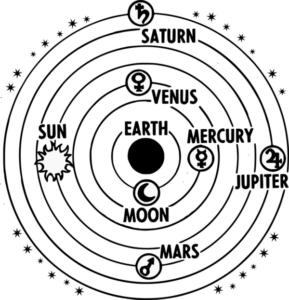

The Dominant Ethical Paradigm

Excerpt from Kierkegaard´s Fear and Trembling: Problem 1

The ethical as such is the universal, it applies to everyone, and the same thing is expressed from another point of view by saying that it applies every instant. It reposes immanently in itself, it has nothing without itself which is its telos, but is itself telos for everything outside it, and when this has been incorporated by the ethical it can go no further. Conceived immediately as physical and psychical, the particular individual is the particular which has its telos in the universal, and its task is to express itself constantly in it, to abolish its particularity in order to become the universal. As soon as the individual would assert himself in his particularity over and against the universal he sins, and only by recognizing this can he again reconcile himself with the universal. Whenever the individual after he has entered the universal feels an impulse to assert himself as the particular, he is in temptation (Anfechtung), and he can labor himself out of this only by abandoning himself as the particular in the universal. If this be the highest thing that can be said of man and of his existence, then the ethical has the same character as man’s eternal blessedness, which to all eternity and at every instant is his telos…

…if the ethical (i.e. the moral) is the highest thing, and if nothing incommensurable remains in man in any other way but as the evil (i.e. the particular which has to be expressed in the universal), then one needs no other categories besides those which the Greeks possessed or which by consistent thinking can be derived from them.

Secular Ethics

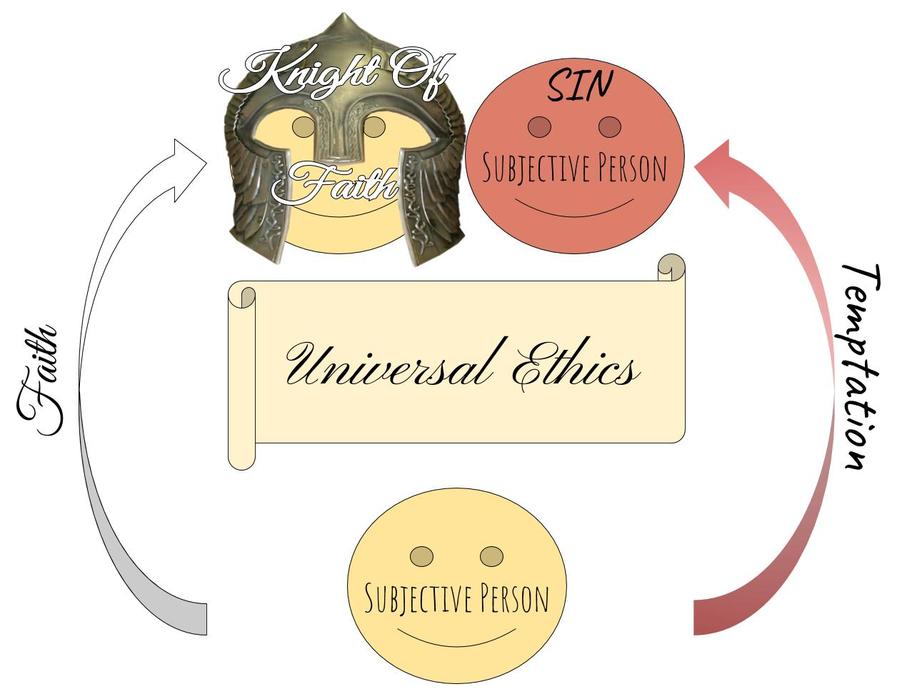

Kierkegaard begins this section of his work Fear and Trembling by describing what he takes to be the dominant ethical paradigm of his time. In it, a person is a subjective being whose “telos” is the ethical. This ethical force is objective and universal, meaning it is true independent of humans perceiving it and it is true in all contexts for all time.

Sin, in this paradigm, would be to assert oneself as ‘above,’ or more important than, the ethical imperatives, and temptation is the impulse to commit sin. For example, when you are taking an exam, you know the ethical imperative is to not cheat, but you might be tempted to do so because it would get you a better grade. If you choose to cheat, you would be asserting that your own whims are more important than the ethical imperative – you would be placing your particularity above the universal.

If this paradigm is correct, then Kierkegaard says the work of ethical theory is pretty much complete! Aristotle, Plato, and the rest of the Ancient Greek philosophers had it all figured out, and “man’s eternal blessedness,” which Kierkegaard defines as a person’s telos, is simply to align themselves as much as possible with the ethical, which is the telos of all things, including people.

Thought Experiment

The Binding of Isaac

The Problem of Abraham

The Problem of Abraham

-

Genesis 22:1-19

-

The Problem of Abraham

1 Some time later God tested Abraham. He said to him, “Abraham!”

“Here I am,” he replied.

2 Then God said, “Take your son, your only son, whom you love—Isaac—and go to the region of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on a mountain I will show you.”

3 Early the next morning Abraham got up and loaded his donkey. He took with him two of his servants and his son Isaac. When he had cut enough wood for the burnt offering, he set out for the place God had told him about. 4 On the third day Abraham looked up and saw the place in the distance. 5 He said to his servants, “Stay here with the donkey while I and the boy go over there. We will worship and then we will come back to you.”

6 Abraham took the wood for the burnt offering and placed it on his son Isaac, and he himself carried the fire and the knife. As the two of them went on together, 7 Isaac spoke up and said to his father Abraham, “Father?”

“Yes, my son?” Abraham replied.

“The fire and wood are here,” Isaac said, “but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?”

8 Abraham answered, “God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son.” And the two of them went on together.

9 When they reached the place God had told him about, Abraham built an altar there and arranged the wood on it. He bound his son Isaac and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood. 10 Then he reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son. 11 But the angel of the Lord called out to him from heaven, “Abraham! Abraham!”

“Here I am,” he replied.

12 “Do not lay a hand on the boy,” he said. “Do not do anything to him. Now I know that you fear God, because you have not withheld from me your son, your only son.”

13 Abraham looked up and there in a thicket he saw a ram[a] caught by its horns. He went over and took the ram and sacrificed it as a burnt offering instead of his son. 14 So Abraham called that place The Lord Will Provide. And to this day it is said, “On the mountain of the Lord it will be provided.”

15 The angel of the Lord called to Abraham from heaven a second time 16 and said, “I swear by myself, declares the Lord, that because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, 17 I will surely bless you and make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and as the sand on the seashore. Your descendants will take possession of the cities of their enemies, 18 and through your offspring[b] all nations on earth will be blessed,[c] because you have obeyed me.”

19 Then Abraham returned to his servants, and they set off together for Beersheba. And Abraham stayed in Beersheba.

Now the story of Abraham contains such a teleological suspension of the ethical. There have not been lacking clever pates and profound investigators who have found analogies to it. Their wisdom is derived from the pretty proposition that at bottom everything is the same. If one will look a little more closely, I have not much doubt that in the whole world one will not find a single analogy (except a later instance which proves nothing), if it stands fast that Abraham is the representative of faith, and that faith is normally expressed in him whose life is not merely the most paradoxical that can be thought but so paradoxical that it cannot be thought at all. He acts by virtue of the absurd, for it is precisely absurd that he as the particular is higher than the universal. This paradox cannot be mediated; for as soon as he begins to do this he has to admit that he was in temptation, and if such was the case, he never gets to the point of sacrificing Isaac, or, if he has sacrificed Isaac, he must turn back repentantly to the universal. By virtue of the absurd he gets Isaac again.

Kierkegaard is a Christian, and thus he believes that the Bible, if not literally true, provides stories with true lessons about human nature. He believes Abraham poses a major problem for the dominant ethical paradigm. The ethical imperative is to not kill his son, yet he “suspends” this telos in favor of his own particular interest, which by the conventional understanding must be considered a state of temptation for which he must repent. And yet, we are told that Abraham represents the epitome of faith – that he is an example of a man living out his eternal blessedness. And, in the end, he is rewarded by getting his son back. How can this be? Abraham is clearly a moral monster, yet he is the epitome of faith and eternal blessedness?

What Kierkegaard raises in Problema 1 is a question of biblical interpretation: How are we to understand the binding of Isaac? What does this story tell us about the nature of humankind?

Kierkegaard’s Argument So Far

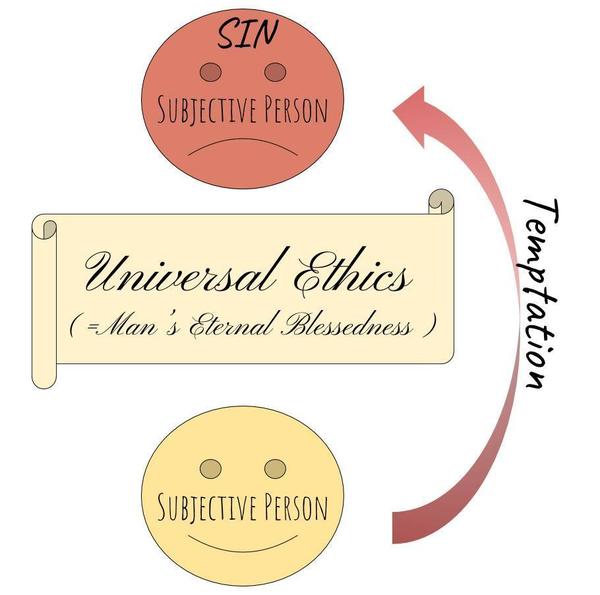

Premise 1) Universal Ethics = Eternal Blessedness

- Corollary 1a) Man’s telos is Universal Ethics

- Corollary 1b) Man’s telos is his Eternal Blessedness

Premise 2) Abraham is not acting according to universal ethics.

- 2a) From 1a and 2, it follows that Abraham is suspending his telos.

Premise 3) Abraham is eternally blessed.

- 3a) From 1b and 3, it follows that Abraham is fulfilling his telos.

4) CONTRADICTION! By steps 2a and 3a, Abraham is simultaneously suspending and fulfilling his telos.

5) When an argument reaches a contradiction, one of its premises must be false. So either 1, 2, or 3 is false.

6) Premise 3 is surely true, because we are told by the Bible that it is so.

The Tragic Heroes: Inadequate Answers

The Tragic Heroes: Inadequate Answers

-

Abraham: A Tragic Hero?

-

Tragic Heroes: Agamemnon, Jephthah, and Brutus

-

Abraham: Overstepping the Ethical

Abraham’s relation to Isaac, ethically speaking, is quite simply expressed by saying that a father shall love his son more dearly than himself. Yet within its own compass the ethical has various gradations. Let us see whether in this story there is to be found any higher expression for the ethical such as would ethically explain his conduct, ethically justify him in suspending the ethical obligation toward his son, without in this search going beyond the teleology of the ethical.

Now Kierkegaard considers whether Premise 2, that Abraham is not acting according to universal ethics, is false. Universal ethical imperatives, he says, come in degrees (for example, perhaps feeding your family is a stronger ethical imperative than not stealing). Thus, perhaps Abraham suspended his ethical imperative towards his son in order to follow a stronger ethical imperative. To see if this could be true, Kierkegaard considers several similar stories from traditional mythology in which a child was sacrificed to serve some greater ethical purpose.

Agamemnon

When an undertaking in which a whole nation is concerned is hindered, when such an enterprise is brought to a standstill by the disfavor of heaven, when the angry deity sends a calm which mocks all efforts, when the seer performs his heavy task and proclaims that deity demands a young maiden as a sacrifice — then will the father heroically make the sacrifice. He will magnanimously conceal his pain, even though he might wish that he were “the lowly man who dares to weep,” not the king who must act royally. And though solitary pain forces its way into his breast, he has only three confidants among the people, yet soon the whole nation will be cognizant of his pain, but also cognizant of his exploit, that for the welfare of the whole he was willing to sacrifice her, his daughter, the lovely young maiden. O charming bosom! O beautiful cheeks! O bright golden hair! (v.687). And the daughter will affect him by her tears, and the father will turn his face away, but the hero will raise the knife. — When the report of this reaches the ancestral home, then will the beautiful maidens of Greece blush with enthusiasm, and if the daughter was betrothed, her true love will not be angry but be proud of sharing in the father’s deed, because the maiden belonged to him more feelingly than to the father.

Jephthah

When the intrepid judge who saved Israel in the hour of need in one breath binds himself and God by the same vow, then heroically the young maiden’s jubilation, the beloved daughter’s joy, he will turn to sorrow, and with her all Israel will lament her maiden youth; but every free-born man will every stout-hearted woman will admire Jephtha, and every maiden in Israel will wish to act as did his daughter. For what good would it do if Jephtha were victorious by reason of his vow if he did not keep it? Would not the victory again be taken from the nation?

Brutus

When a son is forgetful of his duty, when the state entrusts the father with the sword of justice, when the laws require punishment at the hand of the father, then will the father heroically forget that the guilty one is his son, he will magnanimously conceal his pain, but there will not be a single one among the people, not even the son, who will not admire the father, and whenever the law of Rome is interpreted, it will be remembered that many interpreted it more learnedly, but none so gloriously as Brutus.

If, on the other hand, while a favorable wind bore the fleet on with swelling sails to its goal, Agamemnon had sent that messenger who fetched Iphigenia in order to be sacrificed; if Jephtha, without being bound by any vow which decided the fate of the nation, had said to his daughter, “Bewail now thy virginity for the space of two months, for I will sacrifice thee”; if Brutus had had a righteous son and yet would have ordered the lictors to execute him — who would have understood them? If these three men had replied to the query why they did it by saying, “It is a trial in which we are tested,” would people have understood them better?

When Agamemnon, Jephtha, Brutus at the decisive moment heroically overcome their pain, have heroically lost the beloved and have merely to accomplish the outward sacrifice, then there never will be a noble soul in the world who will not shed tears of compassion for their pain and of admiration for their exploit. If, on the other hand, these three men at the decisive moment were to adjoin to their heroic conduct this little word, “But for all that it will not come to pass,” who then would understand them? If as an explanation they added, “This we believe by virtue of the absurd,” who would understand them better? For who would not easily understand that it was absurd, but who would understand that one could then believe it?

The difference between the tragic hero and Abraham is clearly evident. The tragic hero still remains within the ethical. He lets one expression of the ethical find its telos in a higher expression of the ethical; the ethical relation between father and son, or daughter and father, he reduces to a sentiment which has its dialectic in the idea of morality. Here there can be no question of a teleological suspension of the ethical.

With Abraham the situation was different. By his act he overstepped the ethical entirely and possessed a higher telos outside of it, in relation to which he suspended the former. For I should very much like to know how one would bring Abraham’s act into relation with the universal, and whether it is possible to discover any connection whatever between what Abraham did and the universal . . . except the fact that he transgressed it. It was not for the sake of saving a people, not to maintain the idea of the state, that Abraham did this, and not in order to reconcile angry deities. If there could be a question of the deity being angry, he was angry only with Abraham, and Abraham’s whole action stands in no relation to the universal, is a purely personal undertaking. Therefore, whereas the tragic hero is great by reason of his moral virtue, Abraham is great by reason of a personal virtue. In Abraham s life there is no higher expression for the ethical than this, that the father shall love his son. Of the ethical in the sense of morality there can be no question in this instance. In so far as the universal was present, it was indeed cryptically present in Isaac, hidden as it were in Isaac’s loins, and must therefore cry out with Isaac’s mouth, “Do it not! Thou art bringing everything to naught.”

Key Principle

Kierkegaard’s Solution: Faith

Kierkegaard’s Solution: Faith

-

Faith: The Teleological Suspension of the Ethical

-

A New Picture

-

The Risk!

-

Arcade Fire’s Joan of Arc

Why then did Abraham do it? For God’s sake, and (in complete identity with this) for his own sake. He did it for God’s sake because God required this proof of his faith; for his own sake he did it in order that he might furnish the proof. The unity of these two points of view is perfectly expressed by the word which has always been used to characterize this situation: it is a trial, a temptation (Fristelse). A temptation — but what does that mean? What ordinarily tempts a man is that which would keep him from doing his duty, but in this case the temptation is itself the ethical.. .which would keep him from doing God’s will.

Here is evident the necessity of a new category if one would understand Abraham. Such a relationship to the deity paganism did not know. The tragic hero does not enter into any private relationship with the deity, but for him the ethical is the divine, hence the paradox implied in his situation cannot be mediated in the universal…

But now when the ethical is thus teleologically suspended, how does the individual exist in whom it is suspended? He exists as the particular in opposition to the universal. Does he then sin? For this is the form of sin, as seen in the idea. Just as the infant, though it does not sin, because it is not as such yet conscious of its existence, yet its existence is sin, as seen in the idea, and the ethical makes its demands upon it every instant. If one denies that this form can be repeated [in the adult] in such a way that it is not sin, then the sentence of condemnation is pronounced upon Abraham. How then did Abraham exist? He believed. This is the paradox which keeps him upon the sheer edge and which he cannot make clear to any other man, for the paradox is that he as the individual puts himself in an absolute relation to the absolute. Is he justified in doing this? His justification is once more the paradox; for if he is justified, it is not by virtue of anything universal, but by virtue of being the particular individual.

Faith is precisely this paradox, that the individual as the particular is higher than the universal, is justified over against it, is not subordinate but superior — yet in such a way, be it observed, that it is the particular individual who, after he has been subordinated as the particular to the universal, now through the universal becomes the individual who as the particular is superior to the universal, for the fact that the individual as the particular stands in an absolute relation to the absolute. This position cannot be mediated, for all mediation comes about precisely by virtue of the universal; it is and remains to all eternity a paradox, inaccessible to thought. And yet faith is this paradox — or else (these are the logical deductions which I would beg the reader to have in mente at every point, though it would be too prolix for me to reiterate them on every occasion) — or else there never has been faith . . .precisely because it always has been. In other words, Abraham is lost.

Thus Premise 2 is confirmed to be true – Abraham is not acting according to any ethical principle. And Christians must accept Premise 3, that the story of Abraham is a representation of faith. Therefore, it follows that Premise 1, that man’s eternal blessedness is the same as universal ethics, must be false. Kierkegaard argues that this means we must accept the paradoxical idea that faith is the assertion of yourself as more important than universal ethics, despite the fact that everything we know indicates that we are not. To become a “knight of faith,” to use Kierkegaard’s term for an eternally blessed person like Abraham, you must blindly assert God’s Will as your guide over and above your ethical obligations. Kierkegaard says this paradox cannot be “mediated,” or understood, because humans can only think in terms of universal ethics – we lack the ability to understand God’s Will beyond how it is expressed in the guiding ethics of the world.

Therefore, though Abraham arouses my admiration, he at the same time appalls me. He who denies himself and sacrifices himself for duty gives up the finite in order to grasp the infinite, and that man is secure enough. The tragic hero gives up the certain for the still more certain, and the eye of the beholder rests upon him confidently. But he who gives up the universal in order to grasp something still higher which is not the universal — what is he doing? Is it possible that this can be anything else but a temptation (Anfechtung)? And if it be possible . . . but the individual was mistaken — what can save him? He suffers all the pain of the tragic hero, he brings to naught his joy in the world, he renounces everything . . . and perhaps at the same instant debars himself from the sublime joy which to him was so precious that he would purchase it at any price. Him the beholder cannot understand nor let his eye rest confidently upon him. Perhaps it is not possible to do what the believer proposes, since it is indeed unthinkable…

When a man enters upon the way, in a certain sense the hard way of the tragic hero, many will be able to give him counsel; to him who follows the narrow way of faith no one can give counsel, him no one can understand.

From this description, we can immediately see the tremendous risk involved with being a knight of faith: How can you be sure what you are doing is what God wants, especially when everything and everyone points to the fact that it is wrong? The way of faith looks an awful lot like the way of sin from the outside, so deciding to assert yourself above the universal is a major risk. But Kierkegaard’s understanding of the story of Abraham presents a compelling argument that this is exactly what faith is: believing in and doing something despite a lack of evidence, or even despite evidence to the contrary. This is what Kierkegaard calls the “Leap of Faith,” and it is a fundamental tenet of the philosophy known as Christian Existentialism. So do you have the courage to take the leap, and perhaps more importantly, is it worth the risk?

Acknowledgements

This digital essay was prepared by GGL Fellow Sam Kennedy.