Doubt Everything: Descartes

Refusing to Believe

We have already encountered skepticism in philosophy, when we read Socrates’s Apology. But now we are going to consider how skepticism was revived as a virtue during the Enlightenment. And, like any virtue, intellectual humility can be a virtue that can be difficult to get right.

Descartes and Skepticism in the Enlightenment

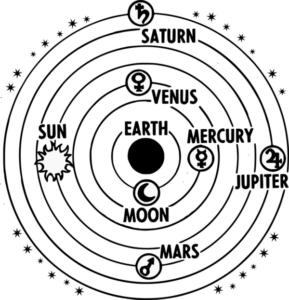

Rene Descartes (1596-1650) was a mathematician and philosopher writing in the beginning of the era we now call the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment is notable for a few trends. Science became more unified and the method of experiment became appreciated as a reliable way of knowing about the world. Many new scientific disciplines were formed. Philosophers opened new questions about the role of religion in personal and civic life. At the heart of this was an ambition to both push the limits of human knowledge and discover the best ways of coming to have knowledge.

In this text, Descartes wrestles with this question: how can we know our beliefs are justified? How can we root out our biases? This is the theme of the Meditations on First Philosophy. We are reading selections the first two of these Meditations today. If you want to download a PDF of all six of Descartes’ Meditations, you can access one here. (This translation is from philosopher Jonathan Bennett.)

Here ND Prof Paddy Blanchette introduces Descartes’ view of knowledge and describes the difference between a priori and a posteriori belief and knowledge.

Descartes Attempts to Doubt His Senses

Descartes Attempts to Doubt His Senses

-

Are some perceptions always trustworthy?

-

… No. Any perception might be a dream.

-

Can I Tell Whether I’m Asleep?

-

… No. Some dreams are very vivid.

Yet although the senses sometimes deceive us about objects that are very small or distant, that doesn’t apply to my belief that I am here, sitting by the fire, wearing a winter dressing-gown, holding this piece of paper in my hands, and so on. It seems to be quite impossible to doubt beliefs like these, which come from the senses. Another example: how can I doubt that these hands or this whole body are mine? To doubt such things I would have to liken myself to brain-damaged madmen who are convinced they are kings when really they are paupers, or say they are dressed in purple when they are naked, or that they are pumpkins, or made of glass. Such people are insane, and I would be thought equally mad if I modeled myself on them.

What a brilliant piece of reasoning! As if I were not a man who sleeps at night and often has all the same experiences while asleep as madmen do when awake—indeed sometimes even more improbable ones. Often in my dreams I am convinced of just such familiar events— that I am sitting by the fire in my dressing-gown—when in fact I am lying undressed in bed!

Yet right now my eyes are certainly wide open when I look at this piece of paper; I shake my head and it isn’t asleep; when I rub one hand against the other, I do it deliberately and know what I am doing. This wouldn’t all happen with such clarity to someone asleep.

Indeed! As if I didn’t remember other occasions when I have been tricked by exactly similar thoughts while asleep! As I think about this more carefully, I realize that there is never any reliable way of distinguishing being awake from being asleep. This discovery makes me feel dizzy, which itself reinforces the notion that I may be asleep!

Here Descartes introduces a theme explored in many science fiction films. For example, Inception:

(Developer note: Video that was embedded here has been removed from YouTube. “Inception” is available on most major platforms.)

Argument

The Dreaming Argument

Here is one way we might try to outline Descartes’ Dreaming Argument:

- If I know something, it is because my senses are not deceiving me.

- When I sleep, my senses deceive me.

- I do not know for certain whether I am awake or asleep.

Therefore, I do not anything (at least, anything sensory).

Is the argument valid? Think of counterexamples. We will discuss these in class.

Objection

Objection: Some Beliefs are Certain Even in Dreams?

Descartes then wonders if there are some beliefs we know to be true, even in dreams…

Suppose then that I am dreaming—it isn’t true that I, with my eyes open, am moving my head and stretching out my hands. Suppose, indeed that I don’t even have hands or anybody at all. Still, it has to be admitted that the visions that come in sleep are like paintings: they must have been made as copies of real things; so at least these general kinds of things— eyes, head, hands and the body as a whole—must be real and not imaginary.

For even when painters try to depict sirens and satyrs with the most extraordinary bodies, they simply jumble up the limbs of different kinds of real animals, rather than inventing natures that are entirely new. If they do succeed in thinking up something completely fictitious and unreal—not remotely like anything ever seen before—at least the colors used in the picture must be real. Similarly, although these general kinds of things— eyes, head, hands and so on—could be imaginary, there is no denying that certain even simpler and more universal kinds of things are real. These are the elements out of which we make all our mental images of things—the true and also the false ones. These simpler and more universal kinds include body, and extension; the shape of extended things; their quantity, size and number; the places things can be in, the time through which they can last, and so on.

So it seems reasonable to conclude that physics, astronomy, medicine, and all other sciences dealing with things that have complex structures are doubtful; while arithmetic, geometry and other studies of the simplest and most general things—whether they really exist in nature or not—contain something certain and indubitable. For whether I am awake or asleep, two plus three makes five, and a square has only four sides. It seems impossible to suspect that such obvious truths might be false.

God, Belief, and Philosophical Demons

God, Belief, and Philosophical Demons

-

A Deceptive God?

-

Belief and the Will

-

An Evil Demon

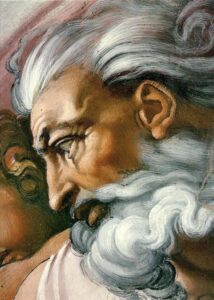

However, I have for many years been sure that there is an all-powerful God who made me to be the sort of creature that I am. How do I know that he hasn’t brought it about that there is no earth, no sky, nothing that takes up space, no shape, no size, no place, while making sure that all these things appear to me to exist?

Some people would deny the existence of such a powerful God rather than believe that everything else is uncertain. Let us grant them—for purposes of argument—that there is no God, and theology is fiction. On their view, then, I am a product of fate or chance or a long chain of causes and effects. But the less powerful they make my original cause, the more likely it is that I am so imperfect as to be deceived all the time—because deception and error seem to be imperfections.

Having no answer to these arguments, I am driven back to the position that doubts can properly be raised about any of my former beliefs. I don’t reach this conclusion in a flippant or casual manner, but on the basis of powerful and well thought-out reasons. So in future, if I want to discover any certainty, I must withhold my assent from these former beliefs just as carefully as I withhold it from obvious falsehoods.

At this point, Descartes finds himself with a problem. Despite having what he takes to be good skeptical arguments, he finds himself lapsing back into his old habit of believing his senses….

It isn’t enough merely to have noticed this, though; I must make an effort to remember it. My old familiar opinions keep coming back, and against my will they capture my belief. It is as though they had a right to a place in my belief-system as a result of long occupation and the law of custom. These habitual opinions of mine are indeed highly probable; although they are in a sense doubtful, as I have shown, it is more reasonable to believe than to deny them. But if I go on viewing them in that light I shall never get out of the habit of confidently assenting to them. To conquer that habit, therefore, I had better switch right around and pretend (for a while) that these former opinions of mine are utterly false and imaginary. I shall do this until I have something to counter-balance the weight of old opinion, and the distorting influence of habit no longer prevents me from judging correctly.

But this strategy raises an even bigger problem: many philosophers think beliefs are not the sort of thing that we can just control at will. To illustrate: try believing (right now) that there’s a million dollars in your bank account. Chances are, you couldn’t do it. You may have entertained the proposition “There’s $1,000,000 in my account,” but merely entertaining a proposition is not sufficient for belief.

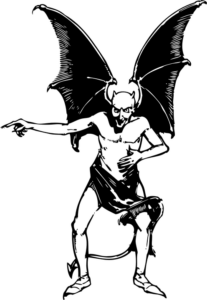

In addition to this, Descartes faces an even bigger problem: he was writing at a time when it when it was unthinkable to call God’s existence into question. By writing about a “deceptive God,” Descartes risked being discredited as a scholar. His solution to both of these problems is somewhat ingenious…

So I shall suppose that some malicious, powerful, cunning demon has done all he can to deceive me—rather than this being done by God, who is supremely good and the source of truth. I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, colors, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely dreams that the demon has contrived as traps for my judgment. I shall consider myself as having no hands or eyes, or flesh, or blood or senses, but as having falsely believed that I had all these things. I shall stubbornly persist in this train of thought; and even if I can’t learn any truth, I shall at least do what I can do, which is to be on my guard against accepting any falsehoods, so that the deceiver—however powerful and cunning he may be—will be unable to affect me in the slightest. This will be hard work, though, and a kind of laziness pulls me back into my old ways. Like a prisoner who dreams that he is free, starts to suspect that it is merely a dream, and wants to go on dreaming rather than waking up, so I am content to slide back into my old opinions; I fear being shaken out of them because I am afraid that my peaceful sleep may be followed by hard labour when I wake, and that I shall have to struggle not in the light but in the imprisoning darkness of the problems I have raised.

Key Principle

Interlude: Knowledge, Belief and Justification

Descartes is primarily interested in the question: Which of my beliefs are knowledge? Here knowledge is a special category of beliefs — beliefs that are both true and sufficiently justified. Let’s draw some distinctions (and hover for examples)

- You can have beliefs that are true but unjustified.

- You can have beliefs that are justified but false.

- Perhaps some truths are neither justified, nor believed, nor false.

The key question for Descartes is where does justification come from and how much do you need in order to be believing rationally? And how should you organize your beliefs as a system?

Other Ways of Seeking Justification

Descartes has a distinctive method for figuring out whether his beliefs are justified. is that the only method? Here ND Prof. Paul Weithman discusses another approach to finding justification — the method of reflective equilibrium.

Argument

What Am I? (Meditation 2)

In the next chapter of the Meditations, Descartes tries to demonstrate that he be confident at the very least that he (Descartes) is thinking… and therefore exists as a thinking thing. Even in dreams this is securely justified belief. Even a demon can’t trick you into thinking you aren’t thinking! This argument is famously called the Cogito Argument, sometimes called the “I Think” Argument.

Even then, if (the evil demon) is deceiving me I undoubtedly exist: let him deceive me all he can, he will never bring it about that I am nothing while I think I am something. So after thoroughly thinking the matter through I conclude that this proposition, I am, I exist, must be true whenever I assert it or think it.

But this ‘I’ that must exist—I still don’t properly understand what it is; so I am at risk of confusing it with something else, thereby falling into error in the very item of knowledge that I maintain is the most certain and obvious of all. To get straight about what this ‘I’ is, I shall go back and think some more about what I believed myself to be before I started this meditation. I will eliminate from those beliefs anything that could be even slightly called into question by the arguments I have been using, which will leave me with only beliefs about myself that are certain and unshakable.

Dissecting the Cogito Argument

Dissecting the Cogito Argument

-

The Cogito in P-C Form

-

What am I?

-

Has Descartes Proven Too Much?

Descartes’ argument is deceptively simple:

- (1) I think now.

- (C) Therefore I exist now.

Is it logically valid? That is… does the premise force the conclusion to be true? That depends on what kind of thing Descartes is — what does the word “I” mean? If we cannot fix the meaning of “I”, then we might worry the argument equivocates. Descartes delves into this in the next section…

Well, then, what did I think I was? A man. But what is a man? Shall I say ‘a rational animal’? No; for then I should have to ask what an animal is, and what rationality is—each question would lead me on to other still harder ones, and this would take more time than I can spare. [COMPARE to Aristotle]. Let me focus instead on the beliefs that spontaneously and naturally came to me whenever I thought about what I was. The first such belief was that I had a face, hands, arms and the whole structure of bodily parts that corpses also have—I call it the body. The next belief was that I ate and drank, that I moved about; and that I engaged in sense-perception and thinking, which I thought were done by the soul. [In this work ‘the soul’ = ‘the mind’; it has no religious implications.] If I gave any thought to what this soul was like, I imagined it to be something thin and filmy— like a wind or fire or ether—permeating my more solid parts. I was more sure about the body, though, thinking that I knew exactly what sort of thing it was. If I had tried to put my conception of the body into words, I would have said this:

By a ‘body’ I understand whatever has a definite shape and position, and can occupy a region of space in such a way as to keep every other body out of it; it can be perceived by touch, sight, hearing, taste or smell, and can be moved in various ways.

I would have added that a body can’t start up movements by itself, and can move only through being moved by other things that bump into it. It seemed to me quite out of character for a body to be able to •initiate movements, or to able to •sense and think, and I was amazed that certain bodies—·namely, human ones·—could do those things.

But now that I am supposing there is a supremely powerful and malicious deceiver who has set out to trick me in every way he can—now what shall I say that I am? Can I now claim to have any of the features that I used to think belong to a body? When I think about them really carefully, I find that they are all open to doubt: I shan’t waste time by showing this about each of them separately. Now, what about the features that I attributed to the soul? Nutrition or movement? Since now I am pretending that I don’t have a body, these are mere fictions. Sense-perception? One needs a body in order to perceive; and, besides, when dreaming I have seemed to perceive through the senses many things that I later realized I had not perceived in that way. Thinking? At last I have discovered it—thought! This is the one thing that can’t be separated from me. I am, I exist—that is certain. But for how long? For as long as I am thinking. But perhaps no longer than that; for it might be that if I stopped thinking I would stop existing; and I have to treat that possibility as though it were actual, because my present policy is to reject everything that isn’t necessarily true. Strictly speaking, then, I am simply a thing that thinks—a mind, or soul, or intellect, or reason, these being words whose meaning I have only just come to know. Still, I am a real, existing thing. What kind of a thing? I have answered that: a thinking thing.

What else am I? I will use my imagination to see if I am anything more. I am not that structure of limbs and organs that is called a human body; nor am I a thin vapour that permeates the limbs—a wind, fire, air, breath, or whatever I imagine; for I have supposed all these things to be nothing ·because I have supposed all bodies to be nothing. Even if I go on supposing them to be nothing, I am still something. But these things that I suppose to be nothing because they are unknown to me—might they not in fact be identical with the I of which I am aware? I don’t know; and just now I shan’t discuss the matter, because I can form opinions only about things that I know. I know that I exist, and I am asking: what is this I that I know? My knowledge of it can’t depend on things of whose existence I am still unaware; so it can’t depend on anything that I invent in my imagination. The word ‘invent’ points to what is wrong with relying on my imagination in this matter: if I used imagination to show that I was something or other, that would be mere invention, mere story-telling; for imagining is simply contemplating the shape or image of a bodily thing. [Descartes here relies on a theory of his about the psychology of imagination.] That makes imagination suspect, for while I know for sure that I exist, I know that everything relating to the nature of body including imagination· could be mere dreams; so it would be silly for me to say ‘I will use my imagination to get a clearer understanding of what I am’—as silly, indeed, as to say ‘I am now awake, and see some truth; but I shall deliberately fall asleep so as to see even more, and more truly, in my dreams’! If my mind is to get a clear understanding of its own nature, it had better not look to the imagination for it.

Well, then, what am I? A thing that thinks. What is that? A thing that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, wants, refuses, and also imagines and senses.

Socratic skepticism originates from Socrates’ pursuit of virtue and wisdom. Descartes’ skepticism originates from his concern for rooting out his biases. Socrates’ initial target was our moral beliefs, especially our beliefs about justice. Descartes took skepticism further, questioning our beliefs about perception and mathematics as well. It is easy to reject skepticism, but we must still answer Descartes’ question: which of our beliefs are justified? Which ones should we trust? We know we have persistent biases. How do rational people manage their biases? That’s our topic for debate in class today.

Summary: Cartesian Skepticism and Cognitive Biases

Summary: Cartesian Skepticism and Cognitive Biases

-

Summary

-

More on Cognitive Biases

-

A Video Summary of Descartes

Socratic skepticism originates from Socrates’ pursuit of virtue and wisdom. Descartes’ skepticism originates from his concern for rooting out his biases. Socrates’ initial target was our moral beliefs, especially our beliefs about justice. Descartes took skepticism further, questioning our beliefs about perception and mathematics as well. It is easy to reject skepticism, but we must still answer Descartes’ question: which of our beliefs are justified? Which ones should we trust? We know we have persistent biases. How do rational people manage their biases? That’s our topic for debate in class today.

Learn more about how psychologists research cognitive biases. Here is a lecture from Nobel-prize winning psychologist, Daniel Kahneman explaining his theory.

Get a summary of some key Cartesian arguments in this Crash Course short:

Acknowledgments

This digital essay was prepared by Paul Blaschko and Meghan Sullivan.