Anscombe’s Intention: Ethics in Action

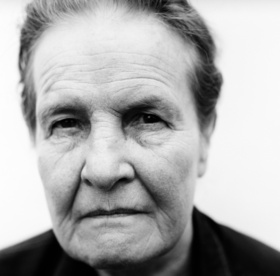

Anscombe & Her Time

Born in Ireland in 1919, Elizabeth Anscombe spent most of her life in England, attending Oxford as a student and later researching and teaching at both Oxford and Cambridge until 1986. She became a close friend and colleague to Ludwig Wittgenstein, one of the greatest philosophers of the twentieth century. Anscombe wrote profusely on the philosophy of mind, action, language, and ethics, introducing a modern revival of Aristotelian virtue ethics.

During the Second World War, when many of the male students and faculty at Oxford were conscripted into the military, Anscombe and three of her female colleagues — Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch — became prominent voices at Oxford, and successfully challenged the approach to moral philosophy that had previously been dominant there. One of Anscombe’s most memorable pieces from that time was “Mr. Truman’s Degree,” where she argued that American President Harry Truman should not receive an honorary degree, based on his use of the atomic bomb.

The following digital essay deals with selections from Anscombe’s Intention (a classic work on the nature of agency) and from “Mr. Truman’s Degree”.

What is Intentional Action?

The following text comes from the beginning sections of Intention, where Anscombe sets up her main question: how do we understand the intentions behind actions? This question is important because we typically only hold people responsible for actions that are intentional and under their control. As Anscombe points out early on in the essay, if I blame you for hitting me and hurting my arm, one way to defend yourself would be to say, “Oh, I didn’t mean to do that! My hand just flinched.” In this example, you’re communitcating that the motion of your hand wasn’t an intentional action, so you should be excused from responsibility. Anscombe’s discussion of intentional action is meant to help us understand what we can hold each other responsible for, and under what circumstances.

From Section 5 of Intention

which a certain sense of the question “why?” is given application; the sense is of course that in which the answer, if positive, gives a reason for acting. But this is not a sufficient statement, because the question “What is the relevant sense of the question ‘Why?’” and “What is meant by ‘reason for acting?’” are one and the same.

To see the difficulties here, consider the question, “Why did you knock the cup off the table?” answered by “I thought I saw a face at the window and it made me jump.” Now, so far I have only characterised reason for acting by opposing it to evidence for supposing the thing will take place–but the “reason” here was not evidence that I was going to knock the cup off the table. Nor can we say that since it mentions something previous to the action, this will be a cause rather than a reason; for if you ask “Why did you kill him?” the answer “He killed my father” is surely a reason rather than a cause, but what it mentions is previous to the action. It is true that we don’t ordinarily think of a case like giving a sudden start when we speak of a reason for acting. We need to find the difference between the two kinds of “reason” without talking about “acting”; and if we do, perhaps we shall discover what is meant by “acting” when it is said with this special emphasis.

Key Principle

Reasons vs. Causes

Here Anscombe is paying close attention to the nuances of what we mean when we use words like “reason” and “cause”. (This focus on language was a hallmark of philosophical inquiry in Anscombe’s time, and remains so today.) We may often use the words “reason” and “cause” as if they were synonymous (and in some cases they might be) but when it comes to determining the intention behind a person’s action, Anscombe thinks they have crucially different senses. Behavior that is “merely caused,” according to Anscombe, doesn’t count as intentional action (and, by extension, isn’t something we can be held responsible for). Spilling the water because you were frightened falls into this category.

On the other hand, murdering someone because that person killed your father is different. Here, the action isn’t merely “caused”; rather, it is undertaken on the basis of a reason. This is why it counts as an intentional action. But while she has distinguished between these two importantly different cases, Anscombe still thinks there’s much more to the story here and tries again to set out a theory of intentional action in terms of her special “Why?” question.

From Section 6 of Intention

To clarify the proposed account, “Intentional actions are ones to which a certain sense of the question ‘why?’ has application”, I will both explain this sense and describe cases shewing the question not to have application.

This question is refused application by the answer: ‘I was not aware I was doing that’. Such an answer is not indeed a proof (since it may be a lie), but a claim, that the question ‘Why did you do it (are you doing it)?’, in the required sense, has no application. It cannot be plausibly given in every case; for example, if you saw a man sawing a plank and asked ‘Why are you sawing that plank?’, and he replied ‘ I didn’t know I was sawing a plank’, you would have to cast about for what he might mean. Possibly he did not know the word ‘plank’ before, and chooses this way of expressing that.

Since a single action can have many different descriptions, e.g. ‘sawing a plank’, ‘sawing oak’, ‘sawing one of Smith’s planks’, ‘making a squeaky noise with the saw’, ‘making a great deal of sawdust’ and so on and so on, it is important to notice that a man may know that he is doing a thing under one description, and not under another. Not every case of this is a case of his knowing that he is doing one part of what he is doing and not another (e.g. he knows he is sawing but not that he is making a squeaky noise with the saw). He may know that he is sawing a plank, but not that he is sawing an oak plank or Smith’s plank; but sawing an oak plank or Smith’s plank is not something else that he is doing besides just sawing the plank that he is sawing.

Descriptions of Action

The fact that actions have various descriptions is a crucially important point for Anscombe. This is because an action might be intentional under one description (for instance “Throwing a baseball in the air”) but not under another (“Breaking a window”). If we want to hold people responsible for some action, then, one question we need to ask is whether they knew (or should have known) that what they were doing could truly be described in this way or that.

Let’s consider a concrete example Anscombe gives us to illustrate this:

A man is pumping water into the cistern which supplies the drinking water of a house. Someone has found a way of systematically contaminating the source with a deadly cumulative poison whose effects are unnoticeable until they can no longer be cured. The house is regularly inhabited by a small group of party chiefs, with their immediate families, who are in control of a great state; they are engaged in exterminating the Jews and perhaps plan a world war. The man who contaminated the source has calculated that if these people are destroyed some good men will get into power who will govern well and secure a good life for all the people; and he has revealed the calculation, together with the fact about the poison, to the man who is pumping. The death of the inhabitants of the house will, of course, have all sorts of other effects.

This man’s arm is going up and down, up and down. Certain muscles, with Latin names which doctors know, are contracting and relaxing. Certain substances are getting generated in some nerve fibres–substances whose generation in the course of voluntary movement interests physiologists. The moving arm is casting a shadow on a rockery where at one place and from one position it produces a curious effect as if a face were looking out of the rockery. Further, the pump makes a series of clicking noises, which are in fact beating out a noticeable rhythm.

Now we ask: What is this man doing? What is the description of his action?

The Well Pumper Case

The Well Pumper Case

This is one of the best-known cases from Anscombe’s Intention. In it, she imagines a man performing a single action: moving a water pump up and down with his arm. She then goes on to consider all the rich descriptions that might be true of that action, such as:

- • Poisoning a houseful of murderous Nazis (Anscombe was in fact writing during WWII)

- • Saving the lives of hundreds or thousands of Jews

- • Contracting certain muscles in his arm

- • Tapping out a certain rhythm with the pump’s handle

Notice: Anscombe doesn’t necessarily think that the man is performing four (or many more) actions here, but a single action of which four (or many more) descriptions could truly be applied.

As we’ve seen, Anscombe holds that a given piece of behavior (or physical movement or whatever) counts as an intentional action if: (a) it’s not merely caused in the individual, and (b) it’s the sort of thing to which we can reasonably expect the subject to give us a reason for doing. To test for this, we can ask — for any given description — “Why are you doing that?”. If the subject responds with a reason, the action is intentional under that description. If not, he’s “refusing to give the ‘why’ question application.” Consider:

- • “Why are you poisoning those Nazis?” Response: “To bring good men into power instead.” INTENTIONAL

- • “Why are you saving the lives of hundreds?” Response: “Because it’s my duty.” INTENTIONAL

- • “Why are you contracting certain muscles in your arm?” Response: “I didn’t realize I was.” NON-INTENTIONAL

- • “Why are you tapping out a certain rhythm with the pump’s handle?” Response: “I didn’t realize I was.” NON-INTENTIONAL

For Anscombe, then, learning how to describe action is a crucial moral capacity, as is attending to how your actions (and their consequences) can be truly described.

This is in part because there are certain descriptions under which we can truly describe an action that are so clear, so obvious, that it doesn’t matter whether or not you try to refuse to answer the “why” question.

Consider the various ways we try to disguise actions by simply re-naming or re-describing them. “The targeted elimination will result in significant collateral damage” is a way of saying, “Bombing our target is going to kill innocent people.” And, for Anscombe — as we’re about to see — this kind of obfuscation is no excuse for the kind of moral horrors often enacted in the course of war.

Mr. Truman’s Degree

While Anscombe was teaching at Oxford, the university decided to grant Harry Truman an honorary degree. This outraged Anscombe who, though no pacifist, considered Truman’s use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to be morally reprehensible. When she objected, her colleagues at the schools voted against her and so she wrote and distributed a pamphlet (part of which is reproduced below) which is known as “Mr. Truman’s Degree.”

In reading through Anscombe’s critique, pay special attention to the role that her account of “intentional action,” with its special emphasis on linguistic descriptions, plays in it.

From the Text

In 1939, on the outbreak of war, the President of the United States asked for assurances from the belligerent nations that civil populations would not be attacked.

In 1945, when the Japanese enemy was known by him to have made two attempts towards a negotiated peace, the President of the United States gave the order for dropping an atom bomb on a Japanese city; three days later a second bomb, of a different type, was dropped on another city. No ultimatum was delivered before the second bomb was dropped.

Set side by side, these events provide enough of a contrast to provoke enquiry. Evidently development has taken place; one would like to see its course plotted. It is not, I think, difficult to give an intelligible account.

For men to choose to kill the innocent as a means to their ends is always murder, and murder is one of the worst of human actions.

When I say that to choose to kill the innocent as a means to one’s ends is murder, I am saying what would generally be accepted as correct. But I shall be asked for my definition of “the innocent”. I will give it, but later. Here, it is not necessary; for with Hiroshima and Nagasaki we are not confronted with a borderline case. In the bombing of these cities it was certainly decided to kill the innocent as a means to an end. And a very large number of them, all at once, without warning, without the interstices of escape or the chance to take shelter, which existed even in the ‘area bombings’ of the German cities.

I have long been puzzled by the common cant about President Truman’s courage in making this decision. Of course, I know that you can be cowardly without having reason to think you are in danger. But how can you be courageous? Light has come to me lately: the term is an acknowledgement of the truth. Mr Truman was brave because, and only because, what he did was so bad. But I think the judgement unsound. Given the right circumstances (for example that no one whose opinion matters will disapprove), a quite mediocre person can do spectacularly wicked things without thereby becoming impressive.

Choosing to kill the innocent as a means to your ends is always murder. Naturally, killing the innocent as an end in itself is murder too; but that is no more than a possible future development for us: in our part of the globe it is a practice that has so far been confined to the Nazis. I intend my formulation to be taken strictly; each term in it is necessary. For killing the innocent, even if you know as a matter of statistical certainty that the things you do involve it, is not necessarily murder. If you attack a lot of military targets, such as munitions factories and naval dockyards, as carefully as you can, you will be certain to kill a number of innocent people; but that is not murder. On the other hand, unscrupulousness in considering the possibilities turns it into murder.

Ethical Descriptions of Action

Throughout the essay, we can see why Anscombe was so insistent in Intention on the importance of accurately labeling or describing our actions. To see that Truman’s action was monstrous, Anscombe thinks, we need only to realize that it was an act of mass murder. While she admits that war sometimes gives us difficult (borderline) cases — such as when we’re not really sure if an approaching group of people are enemy combatants or not, and must make a quick decision — this is not, she claims, such a case. It’s one in which the definition of murder, “the killing of an innocent person as a means to some end,” straightforwardly applies.

Anscombe’s Conclusion

“But where will you draw the line? It is impossible to draw an exact line.” This is a common and absurd argument against drawing any line; it may be very difficult, and there are obviously borderline cases. But we have fallen into the way of drawing no line, and offering as justifications what an uncaptive mind will find only a bad joke. Wherever the line is, certain things are certainly well to one side or the other of it.

Now who are “the innocent” in war? They are all those who are not fighting and not engaged in supplying those who are with the means of fighting. A farmer growing wheat which may be eaten by the troops is not “supplying them with the means of fighting”. Over this, too, the line may be difficult to draw. But that does not mean that no line should be drawn, or that, even if one is in doubt just where to draw the line, one cannot be crystal clear that this or that is well over the line.

It is characteristic of nowadays to talk with horror of killing rather than of murder, and hence, since in war you have committed yourself to killing – for example “accepted an evil” – not to mind whom you kill.

I vehemently object to our action in offering Mr Truman honours, because one can share in the guilt of a bad action by praise and flattery, as also by defending it.

It is possible still to withdraw from this shameful business in some slight degree; it is possible not to go to Encaenia; if it should be embarrassing to someone who would normally go to plead other business, he could take to his bed. I, indeed, should fear to go, in case God’s patience suddenly ends.

Acknowledgements

This essay was prepared by Julia French, Paul Blaschko, and Justin Christy.